Sita Bai had never imagined a life without the well in her village. She has been using water from it for forty years. Her village, Gorano situated in vast Thar desert of Sindh, Pakistan, owed its life to this well. But two years ago, the unimaginable happened. Its water turned toxic and unusable.

Villagers now visit the well as one visits graves of loved ones - with fond memories. Sita and others have covered it with thorny bushes. Barely a kilometer from the well, the sand dunes open into a vast lake filled with stinking, black slush.

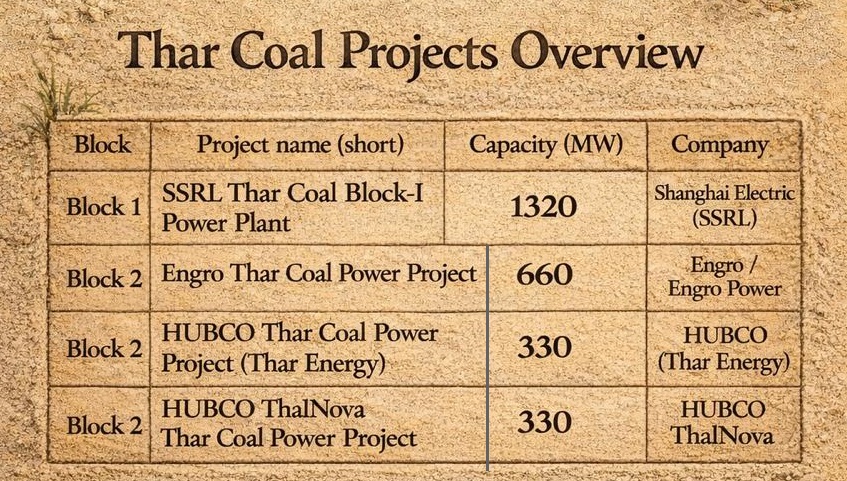

It is an artificial reservoir where Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC) disposes of saline groundwater extracted during its mine dewatering process.The company’s sister concerns - Engro Thar, HUBCO ThalNova, and Thar Energy - run power plants adjacent to the mine by burning the freshly mined coal.

The company is allocated Block II of Thar’s over 9,000 sq km coalfields that are estimated to have 175 billion tons of lignite – a low grade coal.

SECMC employs open pit method to mine lignite, also called brown coal, to fuel its 1320 MW power plants. Earth is stripped layer by layer to expose shallow coal seams. The process scrapes off hundreds of feet of sand leaving huge craters in place of villages and grazing lands.

The company continuously pumps out groundwater to depressurize the pit. The water is mixed with coal, heavy metals and acidic mine drainage (AMD). Open-pit mining provides ideal conditions for production of AMD as underground minerals like pyrite (also known as fool’s gold) produce acid when exposed to air and water.

This highly toxic brew is sent through a 35 km long pipeline to Gorano reservoir. The reservoir is so big that locals call it ‘Gorano dam’.

Slow poisoning of wells

People in Gorano vividly remember the day in 2018 when giant pipes carried the effluent from the mine to the reservoir for the first time.

“Our wells were fine till three years after the Gorano dam was built. In the fourth year, water started tasting a little bitter and by sixth it turned poisonous, and its level also rose,” laments Sita Bai, one of the village elders.

Laboratory tests validate Sita’s observation. A 2022 report by the think tank, Policy Research Institute for Equitable Development (PRIED) found that groundwater deterioration and seepage from the Gorano reservoir had contaminated water sources across 12 nearby villages, impacting over 20,000 people. Mehwish, a researcher associated with PRIED, told Lok Sujag, “Water samples from Gorano’s wells failed every standard for potable water.”

Toxic water in Gorano Dam

But the damage runs deeper than the loss of sweet, freely accessible water from village wells.

The expanding wastewater reservoir has swallowed fields and pastures. Trees that once provided shade to the grazing cattle now stand like burnt matchsticks. “Wastewater from Block II has turned this land sterile. It once grew millet, sorghum, and moong beans, sustaining our life and economy,” says Leela Ram, another affected villager.

The company installed a few reverse osmosis (RO) water plants in the area to compensate for the lost wells. When these plants open, for a few hours a day, everyone rushes with cans to fill what they can. “The RO water is also not fit for drinking,” Mehwish claims. “People have started having severe joint pains since they began consuming it.”

The plant operator takes a day off on Sunday and so the plant stays shut. “Wells never closed and people owned them,” Mehwish points out.

Another ‘compensation’ that the company has granted the community is building of a small public park in Gorano. Leela Ram laughs at the irony: “The whole world comes to see the desert of Thar because it’s a natural park.”

The slides and swings in the company’s park lie rusting, untouched by the children of the desert.

The RO plant was found fenced off and closed for a break during our visit.

In the larger national interest

Poet Imam Ali Jhanjhi belongs to village Wakrio which is also affected by mining in Block II. He wrote a poem in 2008, way before the mining had started, warning his community of the threats to their livelihoods and their ways of living.

I will weep, and you will weep.

We will fall at the feet of others.

And then you will ask me,

Where is our home?

We are but the people of dust,

We are the people of dust.

Imam Ali Jhanjhi (Translated version)

“I warned that the drums and trumpets of development would soon haunt the desert and its people,” he recalls. His words resonated with a few at that time but when the companies began taking over land in 2013, villagers started reciting his poem at protests and sit-ins.

Villagers affected by Gorano dam held a protest sit-in in front of Ismalkot Press Club demanding that the wastewater reservoir be shifted away from their homes. Bheem Raj of Gorano village is a teacher and an activist. He claims the sit in by men and women of his village that started in June 2016 had continued for 635 days.

However, the only response the protesters received from authorities was that the mining project was a matter of national progress and they need to consider and act in larger national interest.

“We are called enemies of progress. We are called traitors. We are told we stand in the way of Pakistan’s development,” Imam Ali laments. Many in the area quip a counter question ‘aren’t we Pakistan too? What about our losses, our suffering?’

Residents of Gorano in the protest camp against the Gorano Dam

Imam Ali has now taken it upon himself to keep a record of the losses. “Seventy percent of Thar depends on livestock. Pastures have shrunk. The mining has reached within two kilometers of our old traditional grazing grounds.”

“Our old wells were 160 to 175 feet deep. Now the mine’s dewatering has pushed the water far below that level and what’s left tastes bitter.” Imam Ali points to the dunes, “There were eighty wells here, and not a single one works now. The company’s boreholes have sucked up sweet water from below our homes.”

People are forced to buy water now. “They charge fifty rupees for one can,” he says adding, “This is too high a price in an area where livelihoods have collapsed.”

From indigenous people to residents of Block II

There is another cruel twist in Wakrio’s plight. The village is directly affected by mining in Block II but according to the block boundaries drawn by engineers and technocrats it is situated in Block III where mining has not yet started. This means that village Wakrio and its inhabitants do not qualify for any compensation or official attention what so ever it may entail.

“They don’t give us water because we’re from Block 3,” Imam Ali says helplessly. “Bro, these blocks were made by you. For us, village is the same, the land is the same, and the sky is the same. But instead of being residents of our own village, we’ve now become ‘people of Block 3’,” he laughs sardonically.

Even basic services are entangled in this ‘block’ division. “The electric lines here hang broken. Sometimes we go fifteen days without power because WAPDA officials can’t get clearance to enter. They say the Chinese are inside, and it’s a CPEC matter,” Imam Ali explains. “When there’s no electricity, the pumps don’t work, and we don’t get any drinking water.”

[CPEC: China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is a part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.]

It is obvious that block location has become a ready excuse to deny the residents their due share in services.

“Sometimes a man from Thar Foundation (the company’s CSR wing) does visit us. He brings an ajrak (Sindhi shawl) for a condolence visit, or a cake on a poet’s birthday,” Imam Ali shares with Lok Sujag but is least impressed by ‘this shallow tokenism’.

Hapless and hopeless, he gestures toward the horizon with his palms open. “Take whatever you want,” he addresses the authorities in absentia. “You’ve already decided to take it anyway.”

Bitu – the toxic mudslide

The desert of Thar lives by the monsoon. The two rainy months of July and August are the only time when it pours here. A good season means ground water is replenished and pond and puddles are brimming. Naturally occurring and rain-filled ponds, called tarhai in vernacular, sustain people and their livestock for five to six months after these annual rains.

Mehwish informs that the dumping of wastewater has destroyed one of the biggest tarhais in village Khario Ghulam Shah. In the nearby village of Jundo Dars, she found three more natural reservoirs ruined, leaving nearly 10,000 livestock with no source of drinking water.

Villagers also report about what they have termed ‘bitu’. Mining in Block I spans roughly 122 square kilometers (over 30,000 acres). The earth removed from pits is piled into heaps. “Whenever it rains, water cascades down these ash-dust mountains and gushes into nearby village like a toxic flood,” Mehwish explains.

In 2023, intense rains triggered one such flood, drowning about 200 homes in Khario Ghulam Shah and Mehran Poto villages. Villagers recounted to Mehwish with great sorrow how this bitu flood swamped their graveyard causing bones to surface from the graves.

The aftermath of these floods is devastating for agriculture. “When mud and ash brought by water dries, it turns into a hard crust. No crop can grow on it,” Mehwish says. To date, the mining company has provided no compensation to farmers in Khario Ghulam Shah whose fields were ruined by these toxic mudflows. A few farmers in Jundo Dars received a token payment of Rs 15,000 per acre, a pittance far below the value of their fertile land.

When Lok Sujag inquired from company about this loss, they simply denied having ‘ever received any formal reports, complaints, or claims relating to loss of agricultural or grazing land.’

These communities, many of whom are from marginalized Hindu castes also known as Dalits, once grew sorghum, millet, moong bean and sesame on their ancestral lands. “What value does fifteen thousand rupees hold compared to the seasonal harvests and food security these lands provided to their families?” asks Mehwish.

‘My home trembles every time the machine starts’

Ahmed Aziz’s house is barely 50 meter away from the boundary wall of the power plant in Block I. His village Warvai is literally under siege. It is surrounded by fences of Shanghai Electric’s power plant and mine from three sides and on the fourth is a guarded check post.

Fencing around Warvai village

The Chinese state-owned Shanghai Electric completed its 1,320 MW mine-mouth power complex under the banner of CPEC in 2022.

“You can see the cracks in our mud walls,” Ahmed points out. “Every time the machines are turned on, our walls shake and ground trembles.” He says his village now lives inside a fortress.

The company fences in Block I now enclose nearly 5,000 acres that include pastures, ponds and traditional passages. The pasture land that Ahmed’s family once used has largely been gobbled up by the project. “Two thousand acres of our gaucher (common grazing land) came under the plant area,” he says quietly.

At the check post, locals are treated as suspects. They have to produce gate passes and identity cards as if they were foreigners on their own soil.

Animals don’t understand new boundaries. They follow age-old paths to water and grass.

“If a cow or a camel strays inside [the plant area], we have to beg the guards to let it out,” Ahmed says. “Sometimes they make us wait for ten days.” Villagers are not allowed to enter the enclosed zone and “if permission is ever granted, it feels like walking into enemy territory,” says Ahmed.

Some villagers claim that when their cattle reach the fence, the company security unleashes dogs to scare or even maul them.

Deprived of most of their grazing, many Warvai families have sold off livestock. “We now keep only a few animals, just enough for milk for home use,” Ahmed says.

The gigawatts of emissions

Thar coal power plants use two main technologies: circulating fluidized bed (CFB) and subcritical pulverized coal boilers.

To understand the environmental impact of these technologies in finer detail, Lok Sujag online interviewed Lauri Myllyvirta who is the lead analyst at Finland-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

Discussing the quality of Thar’s coal, he said that lignite tends to be more problematic regarding two pollutants in particular, sulphur and mercury, mainly because more of this coal has to be burned to produce one unit of energy. These plants are called subcritical.

“Mercury control is especially challenging because mercury exists in different chemical forms. Lignite such as Thar’s typically contains elemental mercury, which is difficult to remove from gases. As a result, lignite power plants tend to have much higher emissions of these two pollutants per unit of electricity produced.”

He informed that these projects emit a wide range of pollutants: sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, different kinds of particulate matter, and mercury (Hg).

According to an analysis by the International Energy Agency (IEA), conventional subcritical coal-fired power plants are among the most carbon-intensive sources of electricity. The IEA estimates that a typical subcritical unit emits around 835 grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt-hour of electricity generated.

This means that such plants have lower thermal efficiency and higher fuel consumption.

Plants in Block 1 emitting smoke into the air

Myllyvirta said that acid-gas emissions (SO₂ and NOₓ) from Thar’s operating coal plants amount to about 71,000 tons per year, particulate matter emissions around 1,800 tons, and mercury emissions around 1,200 kilograms.

To create a comparison, he said that these emissions are equivalent to driving a heavy diesel truck around the world 250,000 times, based on Pakistani emission standards.

They are also equal to the emissions from Bangladesh’s entire transportation sector!

He said these projects would worsen Pakistan’s already poor air quality. The visible dust, he added, indicates very poor particle-control performance.

“I have seen this kind of ash falling from the sky, and it does not happen with proper particle-control systems in place. It definitely raises serious questions about whether these companies are maintaining their pollution-control devices properly.”

Disaster by design

Myllyvirta emphasized that the real issue is not the type of technology being used but how efficient are mechanisms employed for emission-control.

None of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) documents of these plants provide details on mercury capture. He confirmed this point that the emission controls in place severely underestimate mercury emissions.

Myllyvirta, who is also a senior fellow at Asia Society Policy Institute, China Climate Hub says, it is “very clear that technically much better emissions controls are possible,” noting that if a Chinese company is supplying the equipment, “they are very capable of complying with stricter standards as they do it at home, and the same goes for Western suppliers.”

The gap, he argues, lies not in technical capacity but in the standards Pakistan chooses to enforce.

He also mentioned that the lack of disclosure of emissions data makes a significant difference in assessing pollution. In India and Bangladesh, he said, emissions data is much more readily available.

When asked whether the Environmental Impact Assessments of these plants meet global standards, he responded that transparency and disclosure are key elements of any EIA because the core requirement is to inform the public about health impacts.

The International Energy Agency’s Net Zero by 2050 scenario calls for immediate reductions in coal use - a 55 percent decline in unabated coal power generation by 2030 (relative to 2022 levels) and a complete phase-out of unabated coal by 2040.

Pakistan, on the other hand, is moving in the opposite direction.

In its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) submitted under the Paris Agreement, Pakistan pledged an unconditional 17 percent reduction (already a very small pledge) in projected greenhouse emissions by 2035. It also set a target of 62 to 69 percent renewables in the power mix by 2030.

By leaning on ‘indigenous coal’ as the answer to its energy crisis, Pakistan is pumping enormous amounts of pollution into the air which is endangering lives of its people.

The myth of cheap electricity

‘Thar coal reserves can provide up to 100,000 MW of power for next 200 years while Pakistan’s installed capacity currently stands at 46,600 MW.’

In popular public discourse, Thar coal is projected as the magic wand that can end the country’s energy woes by just one move. It works in a country that is desperate to get out of the crisis that has marred all facets of life for past many decades. Proponents of Thar coal argue that using domestic lignite would ensure energy security, self-reliance for the country and cheap electricity for its people. It was, and still is projected as the panacea.

But is Thar coal energy really cheap? Can using local fuel make the country ‘energy secure’?

Data from Central Power Purchasing Agency (CPPA) for the month of October (2025) puts local coal-based power generation cost at Rs 13 per unit compared to Rs 14.39 per unit from imported coal.

So much for all the hype around ‘free/cheap indigenous coal’!

“Only the fuel is local, rest of the machine still runs on dollars as it does in case of any other power plant,” explains Muhammad Abdurrafe, a researcher at the Alternative Law Collective that specializes in energy policies.

Abdurrafe describes these plants as mine-mouth setups which mean the power plant sits next to the mine so that coal is fed directly from pit to furnace saving the cost of transporting coal while plants using imported coal have to add cost of hauling it from far away countries.

“But in all other aspects these (local coal) power plants operate just like any other independent power producers (IPPs) retaining the all too familiar patterns of dollar-indexed debts, generous return guarantees, and hefty capacity payments,” says Abdurrafe.

Abdurrafe explains that though a significant portion of investments, especially in mining, comes from within Pakistan yet this local equity has been indexed to US dollar. “NEPRA itself had objected that if capital is injected in local currency then why is the rate of return indexed in dollars.” But Thar Coal Energy Board, the ‘one-window’ regulatory body, paid no heed.

The Board was established in 2011 by the Government of Sindh to fast track development of coal fields in Thar. It acts as a facilitation authority working with provincial and federal departments as well as local and foreign investors, including CPEC-linked companies, to manage planning, infrastructure coordination, and implementation of Thar coal projects. The Government of Sindh is a joint venture partner in Block II, owning 54 percent of SECMC shares.

Abdurrafe also pointed that the Board’s documents put the levelized cost of coal mining over next 30 years at around 36 USD per ton. “When the raw fuel itself carries such a price tag, the claim of cheap energy becomes a hoax.”

Dr Rubina Illyas is an energy economist at Islamabad-based Pakistan Institute for Development Economics (PIDE) and she too believes that ‘the cheap fuel’ argument does not hold if we look at the situation from consumers’ perspective.

Talking to Lok Sujag she said, “The effective electricity tariff has increased by almost three times over last ten years (Rs 12.50 in 2015 to Rs 34.45 per kWh in 2025) and this increase has been mainly driven by debt, not by cost-related factors.” She implied that cutting cost is not likely to reduce electricity bills for consumers.

When city enters the desert

Abdurrafe is dejected. He believes that no tariff determination or levelized costing or any other financial tricks can possibly capture the damage that has been done to Thar. “They have destroyed a living system that had ecosystems, sustainable livelihoods, water access, community life and what not.”

What upsets him more is the fact all this continues to happen when a better, cheaper and eco-friendly solution is at hand. The installed solar PV capacity in Pakistan has skyrocketed to an estimated 33.35 GW in past three or so years. This is almost thirteen times higher than the current capacity of Thar coal plants (2.64 GW).

The solar boom isn’t limited to Pakistan. The latest data shows that two third of all investment in energy (USD 3.3 trillion) is being directed toward clean energy including renewables, grids, storage, nuclear, efficiency, and electrification while only only about 1.1 trillion is flowing into oil, gas, and coal combined.

“What is the use of these few thousand megawatts when, in the process, you have uprooted thousands of people and taken away their livelihoods and their lives? How can you call this a success?”

Abdul Rauf’s village, Senhri, was bulldozed when mining in Block II started. He was shifted to New Senhri Dars Model Village built by the company in 2019.

“They told us this would be a new life,” he recalls. “Our land would bring prosperity to Pakistan.” For his farmland, the company paid Rs 185,000 per acre as compensation. “That land was worth much more,” Rauf says.

The hut man forced to live under concrete roof is visibly discomforted. He misses the rhythm of the past and keeps drawing comparisons between his two lives.

“We thought our children would study better here, that we would have light, water, and new work,” he says lamenting that, “None of it came true.”

“Back there, we lived close to each other. We shared our harvests. We sat together for kachehri (evening chat gathering) under the trees,” he reminisces.

“Here, everyone stays behind their doors. The ways of city have entered our desert.”

The village that once boasted of its large herds has little space, and fodder, for its cattle now. As the common grazing lands are gone, some households in New Senhri Dars were given small plots as ‘their share’ of community pasture. Neighbors who once collectively grazed their animals now squabble over these tiny parcels of land.

“Mining has now reached the graveyard,” he says in low voice. “The Chinese dumper trucks do not stop. They cannot see who lies underneath.”

Too little too late

In 2018, residents of Warvai village were promised resettlement at a new location within three months. Seven years later the process remains incomplete.

An agreement was drawn up in October 2019 that villagers will vacate half of Warvai immediately and the rest by March 2020, and each household will receive an amount to build a new house.

Subhan Ali, who runs a brick kiln in Warvai, still keeps a photocopy of the agreement. “But the cheques came only for 50 or 60 people, and of only half the promised amount,” he informs.

The payouts are handed to the heads of families and measured plots are allotted to each in a planned colony and this has created another problem.

Traditionally when son of a family is married, he builds his house on a portion of the family land next to his parent’s house. Now that ancestral land is replaced with measured plots in a planned colony with no vacant space where would the newly married build their house?

Subhan and others haven’t been able to work out a way to keep their tradition of families living in clusters alive in their new colony. “A house is not just land,” Subhan says. “It cannot be divided. If a man has three sons, where will they live when they start their families?”

After the initial partial payments in 2019, the process got stuck somewhere and did not move forward smoothly. Many who received payments months and years later complain that the cost of building materials had skyrocketed during the period making the amount insufficient for building a house.

Many others still await final settlement of their dues and claims.

“Planning for the project began in 2003, but after more than twenty years, we still have not received a resettlement plan. When the company wants our land, it gets it in days,” Ahmed, a resident of Warvai remarks. “When it owes us a house, it makes us wait for years.”

Billboards along the main road leading to Blocks I and II, promising a “bright future” for Thar

Aliens in their own country

Abdul Rauf thinks they have been economically downgraded. “We were zamindar, the land was ours. We grew our food and fed our animals. Here (in resettlement colony), we are mazdoor (laborers). If we find a day’s wage, we eat. If not, we sleep hungry.”

Umer (named changed on request), a young man, works as a laborer at one of the coal power plants.

Each day, he leaves home at 3:00 pm and returns at 2:00 am, working an 11-hour shift.

“All the officers come from outside,” he says adding, “Local people like us are just laborers. Everyone works on daily wages through contractors. If you miss a day, you earn nothing. Our jobs are entirely at the whims of the contractors.”

The contract workers do not qualify for any social security, health facility or any other perks.

Umer claims that Rs 9,500 is deducted from his pay each month for food provided at the site but the quality is so poor that he avoids it. “I eat at home before leaving and again when I return,” he says. “Complaining is futile. In return they would taunt ‘Do you eat mutton every day at home?’.”

A dejected Umer says with a stoic face, “They say Thar will change Pakistan. Maybe someday our fate will change too.”

The suffering of common villagers has taken a nasty turn in village Wakrio.

The narrow dirt path passing by the village has become a ‘short-cut’ for heavy dumper trucks. “It’s like Karachi–Hyderabad highway now,” remarks one resident. They carry limestone and gravel to build a new railway line that will connect Thar coalfield to the main railway network.

In August 2025, Noor Mohammad Jhanjhi, a resident of Wakrio, ‘paid the ultimate price’. He lost his 13-year-old son, Muhammad Shan Zeb, who was sharing a ride on a motorcycle when a speeding dumper mowed him down.

Noor Mohammad was sitting in the verandah of his house when we visited him, “The day before the accident, it was my son’s birthday,” he says quietly. He points to the road outside. “It was never built for heavy traffic. It is wide enough for two bullock carts. These trucks have made it a death road.”

The companies use this route as taking the main highway would add about 30 km to their trip.

Noor Mohammad was holding a mobile phone with a photo of the truck driver and the vehicle involved. He did file a complaint with the police but he’s not optimistic. “You know how it is, when the accused are tied to such a big project,” he says, “Everything moves slowly, if at all.”

The method to madness

The most oppressive aspect of life after coal mining, in opinion of most of the Tharis, is the pervasive security apparatus. Villagers are pained at being treated like aliens and intruders on their land. They complain about rude, insulting and humiliating attitude of security personnel.

Complaints about highhandedness of the security establishment are not uncommon. In fact, everyone has a story of humiliation to tell. The case of Dodo Bheel (2021) exemplifies the situation and the relationship between locals and the security setup.

The poor laborer, Dodo Bheel, was accused of theft by security guards of Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company who kept him in illegally confinement for many days and subjected him to severe torture. As his condition deteriorated, he was hastily handed to the police who took him to hospital where he succumbed to his injuries.

A Thari family sitting in their home

The case hit the national news as the federal Ministry of Human Rights sent a fact-finding mission headed by Member National Assembly, Lal Chand Malhi who was Parliamentary Secretary for Human Rights. The province of Sindh and the federal government at that time were governed by two opposing political parties, Pakistan People’s Party and Pakistan Tehreek Insaf respectively, who were working hard to let down each other in every possible way. This tussle may have played a role in making the case public.

Villagers say that many instances of excesses of security personnel either remain unreported or are hushed up. “Whenever we complain, the response from officials is simple: ‘It is our duty to protect the Chinese’,” says Umer.

Qurban Ali Samejo of Islamkot who is an advocate and a member of Thar Citizen Forum documents acts of resistance and repression.

He says, “Even when courts rule in favor of a farmer, the government challenges it in higher courts where the matter remains stuck while the company continues to have its way on the disputed piece of land.”

Qurban can see a pattern to how land is acquired from the villagers. “Company officials don’t come by themselves. They send the Assistant Commissioner with a couple of local waderas (feudal lords). They visit the village and promise schools, jobs, all kinds of facilities if people ‘consent’ to the acquisition. They pressure them to sign. If persuasion fails, then the police enter.”

Villagers are also emotionally blackmailed by repeatedly telling them that “opposing the project means opposing CPEC and opposing CPEC means opposing Pakistan.”

Does Thar have a future?

“Half of Thar’s area falls inside these projects now. If mining continues at this pace, the entire district will end up in companies’ hands,” says a worried Qurban Ali Samejo.

Land in Thar can be put in two categories, surveyed and documented plots and vast tracts of community-managed grazing and farmlands that are not documented as such in official records.

“People have been cultivating the so-called ‘undocumented’ land since the 1930s in some cases. The law says their [ownership] rights mature over time and yet the Revenue Department only compensates for what’s on Form VII [the record-of-rights],” says Samejo explaining further, “So a family that has been farming fifty acres might get payment for only five or nothing at all depending on what the documented record says.”

The state’s failure to document land ownership has become the companies’ gain. The landless, the poorest of all, pay the price by losing their homes, and dignity.

“The issue is simple,” Umer sums up locals’ perspective, “They need our land for Pakistan’s progress. We are ready to give it. But take it on lease, not forever. When the coal is finished, give it back to our children. It’s our inheritance. ”

Views similar to Umer’s reverberate in many discussions across the region. Mehwish, however, believes that it isn’t this simple because purchasing serves the interests of the companies.

“Had they taken the land on lease, they would have to pay annual rent to the villagers and the land would still legally belong to the people,” she explains adding, “By purchasing, the companies got the freedom to treat the land the way they want to. They are not obliged to do this and not that.” In fact, she notes, she hasn’t seen any credible plan for post-mining reclamation and rehabilitation of the area.

But Qurban Ali insists that the companies should be given land on twenty or twenty-five year lease. “When mining will end the land should return to those who have lived on it for centuries.” He thinks that this way the Thar and the Tharis will at least have a future otherwise it will end up as a land of vast craters and toxic ponds.

Lok Sujag contacted Thar Coal Energy Board, the managing authority for the Chinese firm operating in Thar Coal Block I. However, our emails sent to the listed address remained undeliverable. On contacting through other means, its representatives did not respond to our requests.

Response of Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company to our questions is being posted here as such for the sake of record.

Written by Abdullah Cheema

Reporting by Tanveer Ahmad, Asif Riaz

Local coordination :GR Junejo and Ashfaq Laghari

Graphics : Shoaib Tariq and Ali Haider

Mapping and supporting research : Mohsin Mudassar

Camera work : M. Shahzad Malick

This story is supported by the Pulitzer Center

Published on 19 Dec 2025