An ambitious state project in the heart of Pakistan’s Cholistan desert is quietly unraveling. The Green Pakistan Initiative (GPI) launched just two years ago and projected as a climate-smart farming revolution and a pathway to national food security is under a cloud.

The project dreamt of transforming dunes of Cholistan into farmlands by contracting out vast tracts to private companies who were supposed to vanguard a corporate farming revolution.

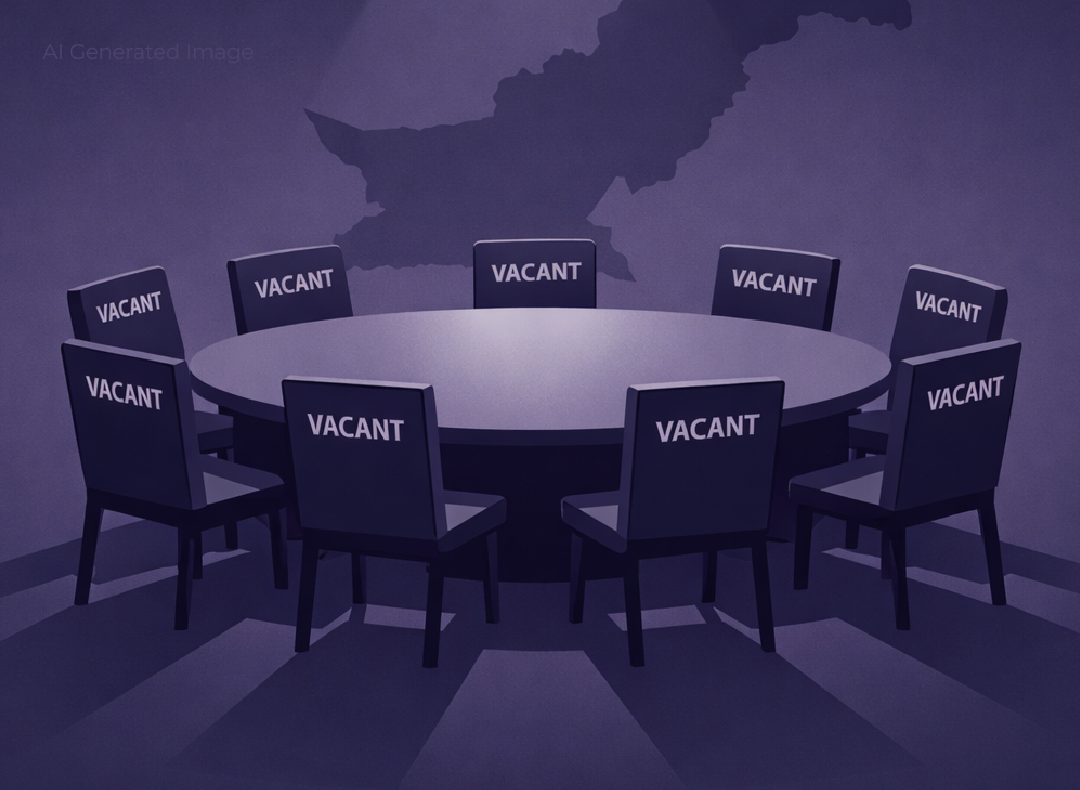

The companies involved in the project are, however, disillusioned. They have one foot out the door.

Between April and November 2025, this scribe along with Lok Sujag colleagues paid 12 visits to five sites of Green Pakistan Initiatives across Punjab, interviewing scores of persons including those responsible for, or working on, the farms of eight different companies in various capacities. Most of them were skeptical and many were open in expressing their disappointment and even in predicting the project’s failure.

There are reports that Unity Food group, one of the biggest investors with a 50,000-acre farm, is withdrawing from the project. They started with a bang but ended with a whimper. The company posted a video on its YouTube channel a year ago documenting the journey of its imported agricultural machinery all the way from China to its site in Cholistan. Now people in the area tell that the machinery is either gathering dust or has been sold out. Our formal requests to the company representatives for their response remained unanswered.

The representative of Fatima Fertilizer, another company with a 50,000-acre farm, however, did inform us that they haven’t even started working on the project yet.

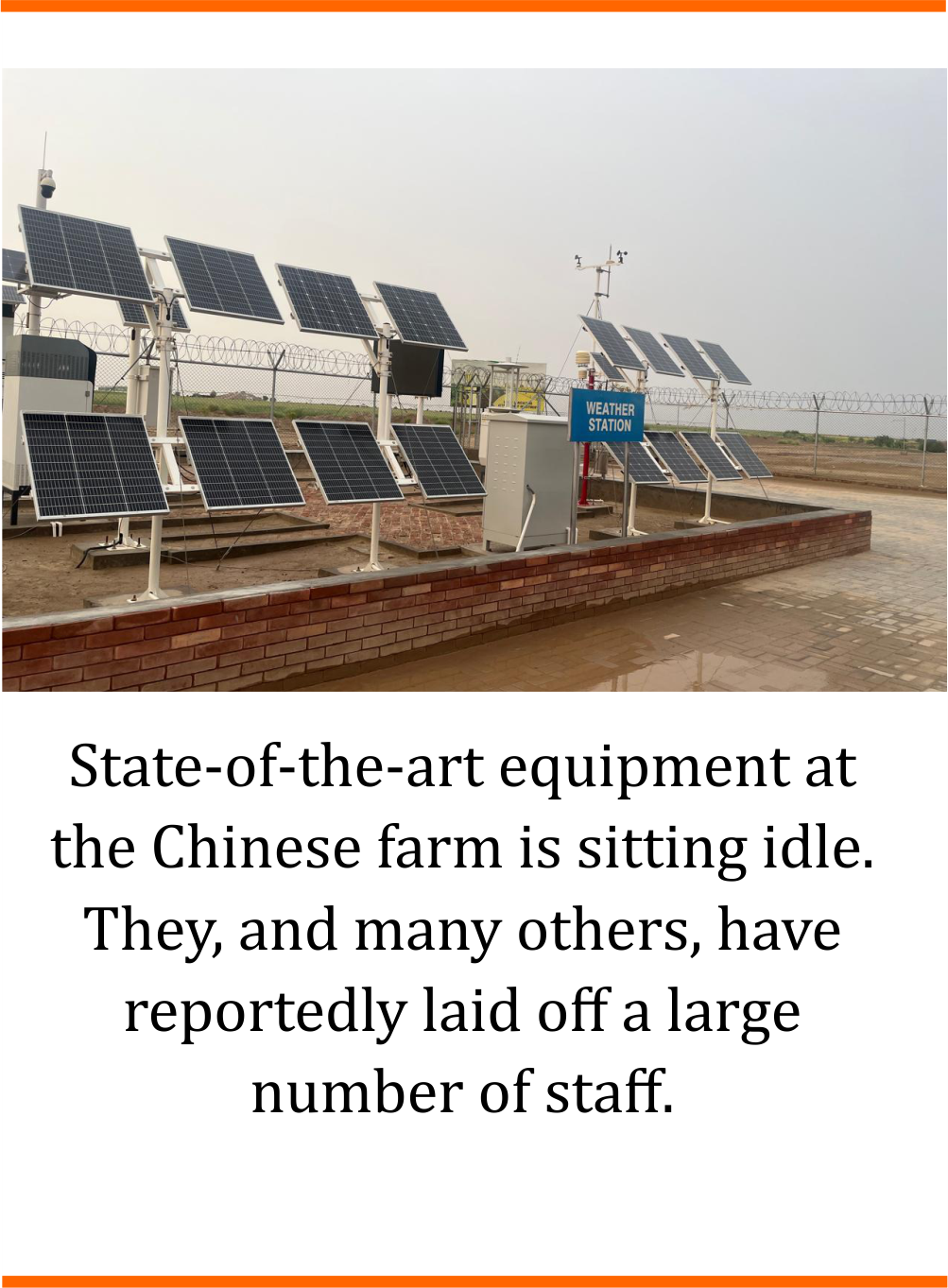

The electronics assembly company, Airlink Communications, had set up a farming venture by the name of Next Agro, and Beaconhouse School Systems had set up Kasalan Foods for the same purpose. Both are reportedly scaling back. SinoPak Guangdong, the only Chinese investor, has also laid-off large numbers of staff.

Pakistan’s 52.8 million acres of farmland is cultivated by its over 10 million farmers. Many experts hold the view that small farm sizes (average 5.1 acres) and traditional farming methods put the country’s agriculture sector on the wrong side of the economies of scale paradigm. Resultantly, it is neither able to meet domestic demands nor can it compete in export markets, which are dominated by countries with high-tech corporate farms of very large sizes.

Green Pakistan Initiative aimed to reverse this.

According to the project’s website it is a joint effort of the government of Pakistan and the Pakistan Army, being implemented by a company named Green Corporate Initiative (GCI) Private Limited. Web searches show that all but one directors of the company are retired senior military officers, while some sources indicate that 90 per cent of the company’s shares are held by the Pakistan Army.

The website says that GCI identifies and acquires culturable wastelands of the provinces on a 30-year lease under joint venture agreements and allocates land parcels to the interested investors to undertake corporate farming. The minimum size of land parcel that GCI offers is one thousand acres.

Many investors were drawn into the project because of the Army’s direct involvement. “We trusted the Army otherwise, we might not have invested,” said one CEO, speaking on condition of anonymity. The trust level was so high that investors relied on verbal promises of abundant water and quality infrastructure. “The paperwork [contracts], however, contained no such guarantees,” said the CEO.

The companies are now battling with saline groundwater and poor to no infrastructure, necessary for modern farming.

Kasalan Foods planned to grow wheat on a 6,000 acre farm. Its ambition evaporated in thin air on first attempt. “Water is the real issue,” said Abdul Manan, head of the company’s farming venture. Their wheat yield last year was a meager seven maunds (maund=40kg) per acre - less than even a quarter of the national average (29.65 maunds) that year. Wheat yield in Australia, the biggest wheat exporter in 2025, was 72.75 maunds per acre.

“Without a sustainable water solution, this project will fail,” Mannan made no bones and added that most of the companies still in operation are just hanging on by growing Rhodes and alfalfa - the two grasses used as cattle fodder.

Rizq, a social enterprise founded by young change-makers with the goal to end hunger and food insecurity, landed itself in this corporate farming experiment. Rizq handles human resource management for farms owned by Pantera Energy Private Limited, which is also growing Rhodes grass to export it to livestock farms in the UAE.

Qasim Javed, CEO of Rizq, terms the experience ‘bittersweet’. He believed that corporate farming could modernise Pakistan’s outdated farming practices. “But the ground reality [of the Cholistan project] is harsh - no roads, no electricity, no internet and water so saline that the only viable option is growing Rhodes grass.”

It is ironic that in a country where 44.7 per cent live below the poverty line, facing severe food insecurity, a project meant to revolutionize agriculture seems to be good for fodder markets of the Middle East only.

Fodder for thought

Driving through the Cholistan desert in peak summer, green swaths of grass fields seem like an illusion. It looks miraculous until you learn what’s keeping it green. Corporate farms are pumping water from the deep - and it is brackish.

Abdul Hafeez manages 4,000 acres of DayZee Farms that are irrigated by groundwater with a Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) level of 1,800 - 2,000 ppm. “Technically wheat, oats, barley and some grasses can be grown with this water,” he explained, “But other factors make most of the grain crops financially unviable. So we stick to Rhodes grass even though it uses more water.”

Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) count refers to concentration of salts and minerals in water. Water with TDS below 1,500 ppm is ideal for irrigation while above 3,000 is harmful for most of the crops. Hafeez estimates that only 20 percent of Cholistan’s underground water has a TDS level of less than 2,000 ppm.

When Kasalan Foods tested their underground water, it registered 3,500-5,000 ppm. They went ahead with sowing wheat on 1,000 acres. Within months, TDS levels spiked to 10,000-25,000 ppm. The crop failed. “The aquifer hasn’t recharged in months as rainfall is scarce. This is existential,” Abdul Mannan was unequivocal.

The Army-run Frontier Works Organization pumps water 10 km away from its land because the water under their own land is too saline. At the adjacent farm of SinoPak Guangdong, state-of-the-art infrastructure sits idle for the same reason. Tube wells had to be drilled nearly 14 km away to access usable water. But bringing it to the point where it is needed remains a challenge. The channels lined with geo-membrane fail in extreme desert heat and the concrete-lined ones are choked by sand from frequent storms.

Sand storms are a constant threat. One CEO, whose company leased 6,000 acres, recounted losing 390 acres of cotton to a storm just as planting neared completion and then after re-sowing another 240 acres was blown away. Losses ran into millions.

The same was reported by Terra Crop Innovation, backed by Alfalah Bank’s Agri Cultivation Fund. They lost 160 acres of cotton to storms this year (2025).

Large farms are ideally irrigated through a central pivot system that sprinkles water on top of crops. It needs certain adjustments for cotton so that showers from above do not knock off flowers or hinder pollination. The companies which planned to grow cotton thus opted for traditional flood irrigation. But flooding porous sandy land consumes massive amounts of water. Abdul Wajid, managing Terra farms, said, “We did trials with crops that consume much less water like moong, guar, soybeans and lentils, but all of them failed completely due to excessive heat and storms.”

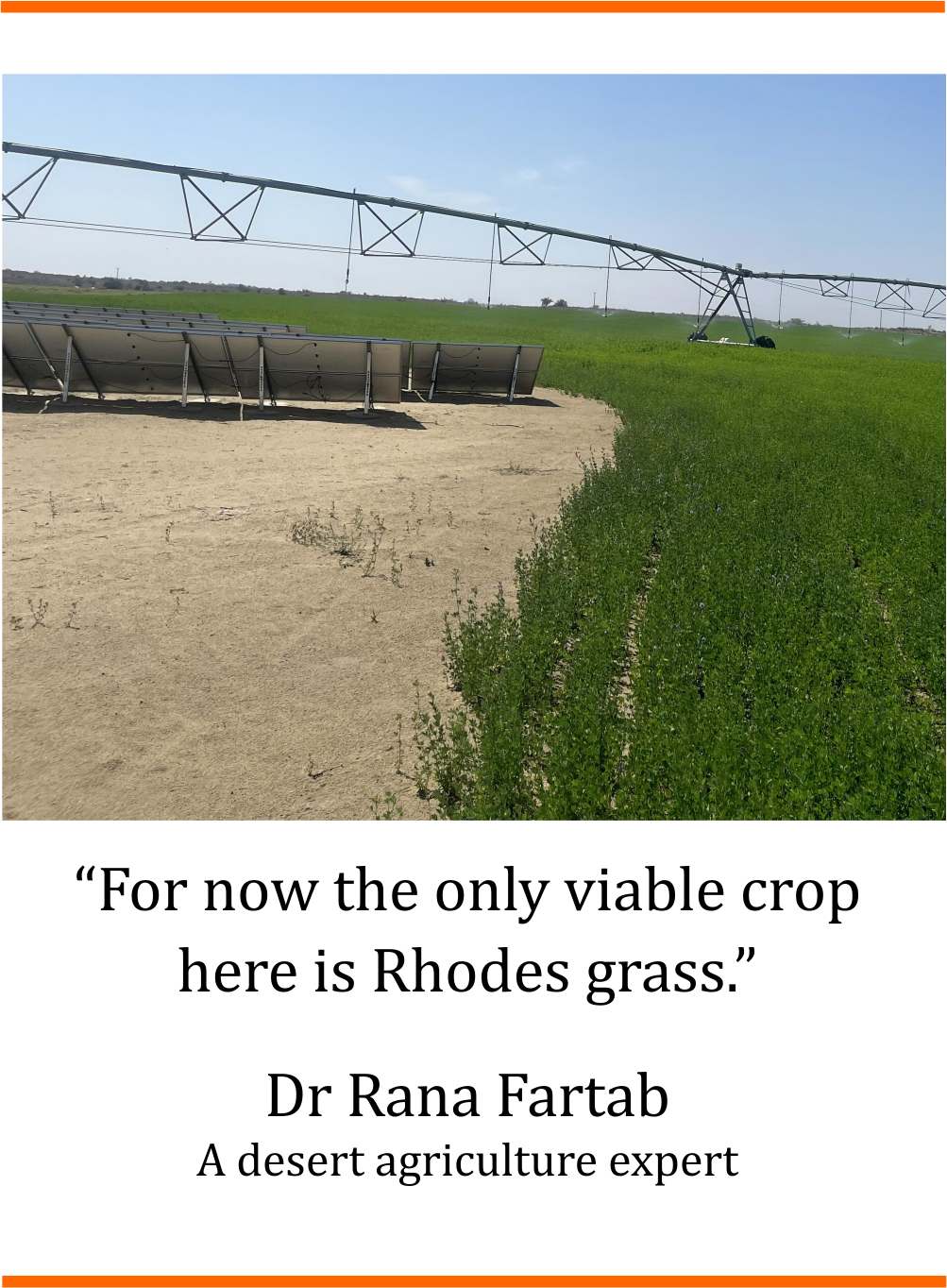

Dr Rana Fartab Shaukat, a desert agriculture specialist, thinks that traditional cropping won’t work here. “I was pressured to grow sesame [on a farm in Cholistan] for its export potential,” he recalled. “I planted it reluctantly, and sandstorms wiped it out within days.”

He advocates phased greening - starting with hardy grasses, then planting trees as windbreakers, and then moving to conventional crops only after 7 to 8 years. But even that, he insists, is impossible without a stable source of water. “For now, the only crop tolerating saline water and offering returns is Rhodes grass.”

Experts warn that relying on saline water for large-scale farming will degrade soil over time. In the hot dry climate, water evaporates quickly but the salts stay, and with little rainfall it doesn’t get flushed down below the root zone. These patterns are widely documented in major technical reviews from bodies like the FAO and the US Salinity Laboratory on saline irrigation. Hydrologist Najam ul Hassan, who has drilled wells in Cholistan for 40 years, says recharge is essential to leach salts from top soil. Najam advocates reviving traditional tobas (ponds) and building recharge wells but insists, “Proper agriculture is not viable here without canal water.”

Standing against a long history

India-Pakistan border drawn in 1947 split the Thar Desert, also known as the Great Indian Desert. Its Pakistani part, falling in Sindh province, retains the name Thar while the southern Punjab part is called Cholistan, or Rohi in vernacular.

In prehistoric times, a mighty river, Hakra, passed through this area, which wasn’t obviously a desert then. River Sutlej used to flow into Hakra, which ran parallel to Indus River and had its own terminus in Arabian Sea. But around ten thousand years ago, geological and climatic changes diverted the Sutlej to its present course, making it a part of the Indus river system, and also caused the Hakra to dry up. Hakra disappeared completely close to the peak of Harappan civilization around four thousand years ago.

The Green Pakistan Initiative stands against a very long history.

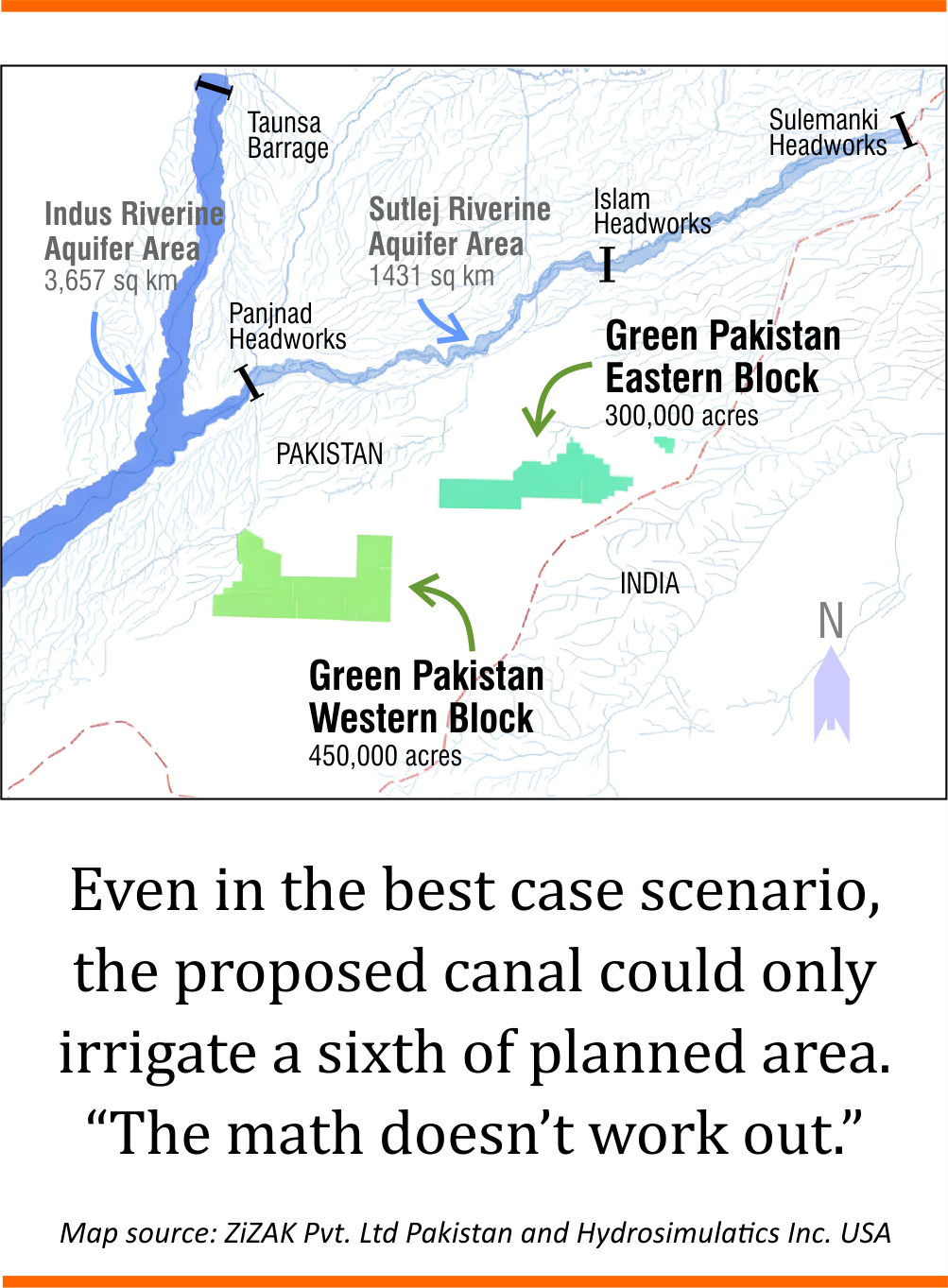

It plans to turn Cholistan green by drawing water from Sutlej through a 176-kilometer long canal. The river Sutlej was allocated to India for ‘unrestricted use’ under the Indus Water Treaty signed between India and Pakistan in 1960 following the independence and partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. As India stopped Sutlej water from crossing the border over the next decade, Pakistan built canals to divert water from its western rivers to command areas of Sutlej.

So Sutlej in Pakistan already runs on borrowed/diverted water. Unsurprisingly, the distribution of river waters is not only hotly contested between India and Pakistan but also within Pakistan. Punjab, being an upstream province with more than half of the country’s cultivated land, is accused by downstream Sindh of drawing more water than its due share. Sindh was thus quick to raise objections to the suggestion (or plan) of providing water to corporate farms in Cholistan from the Sutlej.

Punjab and Sindh are currently ruled by two different political parties, Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) and Pakistan People’s Party, respectively, which have formed a coalition government in the center. Both the coalition partners realize that upsetting the water status quo can put a lot at risk.

Politics aside, experts believe that the proposed canal could never deliver the required amount of water. It was estimated to carry 4,000 cusec to irrigate 750,000 acres of corporate farms. “Even with efficient pivot irrigation, you need 30 cusecs per 1,000 acres in this climate,” said one agronomist, which means that even in the best-case scenario, the proposed canal could irrigate just 133,000 acres or a sixth of the total planned farm area. “The math doesn’t support the plan,” quipped the expert.

The authorities probably had realized this too. A CEO, talking on condition of anonymity, revealed that the canal water wasn’t mentioned in their initial engagements. “We were told we’d get clean water from reservoirs under the Sutlej riverbed,” he said, adding, “That’s what we have invested in.”

In fact, the Green Pakistan Initiative had commissioned a study on alternative ways of irrigation. Experts from Pakistan, the United States and China who conducted the study pointed to Riverbank Filtration (RBF) as a solution. According to an expert who was part of the team conducting the study, Sutlej and Indus riverbed reservoirs offer good-quality, silt-free water in quantities sufficient to support sustainable farming in the desert, without sparking new water conflicts.

After extensive research and the use of modern technologies, the consulting team proposed the Horizontal-Collector Well System to tap into the riverbed reservoirs. This system uses wells placed along the riverbank to collect clean water and move it to a pump station located away from the water’s edge. The pump then lifts and pressurizes the water, sending it through pipes to the farms in the desert.

“We were told the water would be delivered directly to our farms through pipelines, with outlets every 250 acres,” the CEO added. “But the promise has vanished. No updates. No implementation. Just silence.” Our queries to Green Pakistan Initiative about the riverbed filtration, and other aspects of this story, have also remained unanswered.

However, experts warn that riverine aquifers of Sutlej and Indus are the last remaining sources of fresh water in the country and that these should be used with utmost caution, and certainly not for producing water intensive fodder crops for camel and cattle farms in the Middle East.

Many shades of green

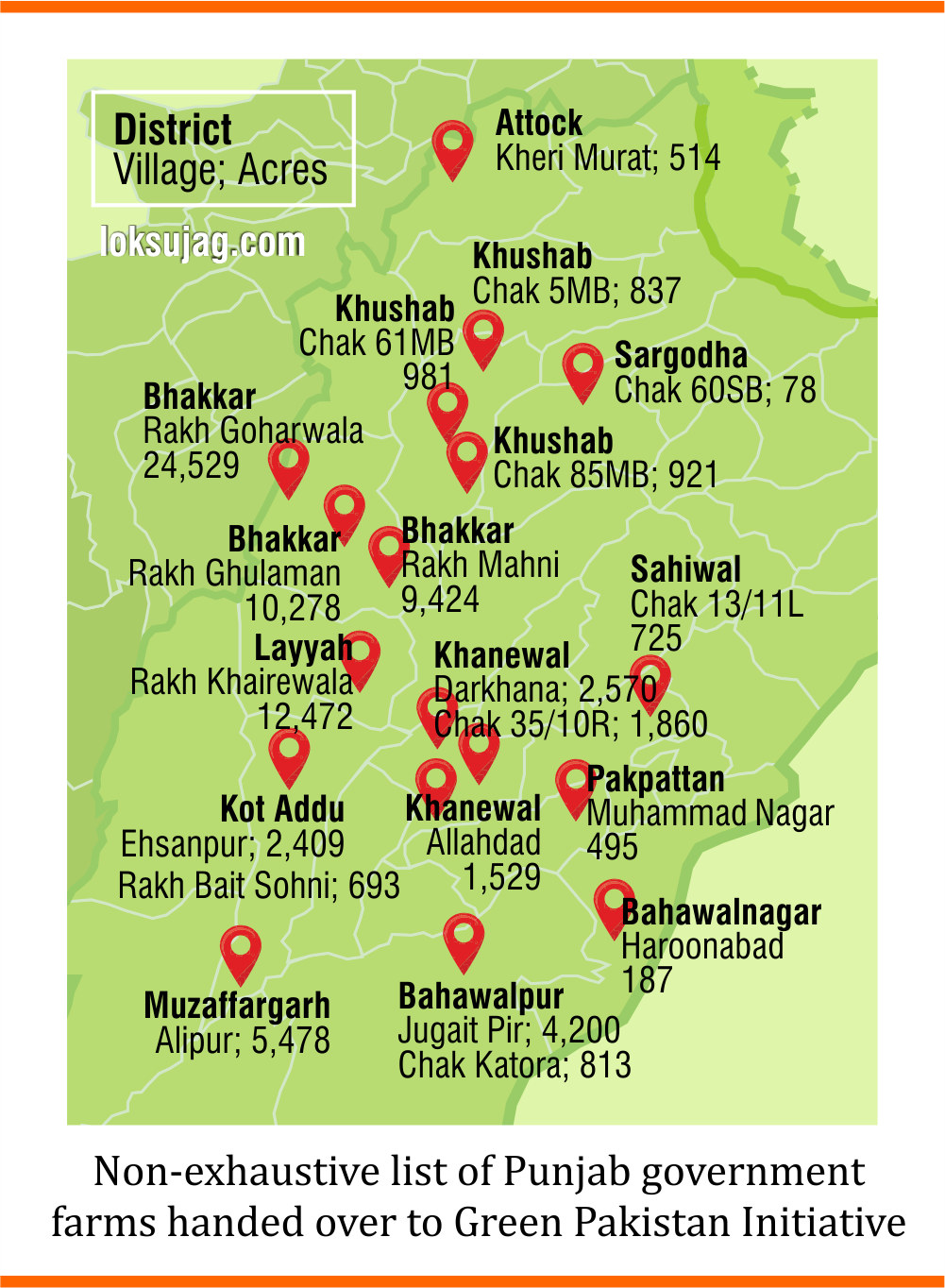

The Green Pakistan Initiative is not limited to the so-called wastelands of Cholistan. ‘To drive agricultural revival through precision farming, mechanization, and corporate investment’, the Initiative also wanted land that is irrigated through established means - canal, tubewells and ponds.

On February 8, 2023, the Directorate of Land of Pakistan Army submitted a formal request to the Punjab Board of Revenue proposing that one hundred thousand acres of irrigated land in Punjab be transferred to the Green Corporate Initiative.

The entire process of identification of state land, clearance from the relevant departments, and approval of the project by the caretaker cabinet was completed over the next 29 days. (As the provincial legislature was dissolved by its chief minister on January 12, 2023, the province was being ruled by a caretaker chief minister appointed by the Election Commission of Pakistan).

Official documents reviewed by Lok Sujag show that the project teams identified 96,571 acres of land spread across 14 districts for potential handover to the Green Corporate Initiative. The caretaker government of Punjab and the Pakistan Army signed the joint venture agreement on March 8 and the process of transfer of land started immediately afterwards.

Owned by the Punjab government, these lands were under control of its various departments including agriculture, livestock, irrigation and forest. These lands were neither barren nor unclaimed and unused. In fact, 27,000 acres of these are being cultivated by tenant farmers since decades under various terms and conditions set in their contracts with the owner departments.

This fact landed the Green Pakistan Initiative into another trouble.

As the Punjab government quickly handed over the identified land to GCI, the new owner asked the tenant farmers to vacate so that the land could be handed over to the investors.

Rakh Ghulaman in district Bhakkar is one of the largest of these public sector farms, with a total area of 10,237 acres of which 2,921 had been contracted to tenant farmers.

Around 200 families live here in seven hamlets spread over a sprawling stretch of farmland. Forefathers of many of them were refugees of the bloody Partition of 1947. They were settled on this state land and given contracts for farming 12.5 acre plots here to help them make a livelihood and share a portion of their produce with the state.

Back then it was a wild expanse covered with thorny bushes and infested with dangerous predators. The tenants hacked through the wilderness with no resource but their bare hands. They toiled tirelessly to turn it green.

“We were so poor,” recalls 70-year-old Haji Matiullah, one of the oldest settlers, “that my father had just one bull [instead of a pair], so he would employ the lone bull on one side of the plow and himself on the other.” The land offered no support. It was instead hostile. “One of my uncles was killed by a wolf,” Matiullah adds, his voice dropping. “That’s the kind of place this was.”

Seven decades later, the fourth generation of these farmers is being asked to walk away – just like that so that the land can be given to rich investors.

The story was repeated 200 kilometers south of Rakh Ghulaman at Ehsanpur seed farm in Kot Addu district. It was like a rude shock for the 350 tenant families who had been tilling 2,000 acres of state land here since the British colonial time. “All tenants must gather in the official building of the seed farm,” the loudspeaker of the local mosque blared. The official told the fazed gathering of tenants: "You must harvest your crops and vacate your homes by April 30 [in just over a month’s time].”

It soon became a pattern. Shamoon Bhatti is a tenant farmer on government-owned livestock farm in Chak Katora, Bahawalpur district. “One Sunday afternoon I went to the village to visit my parents’ graves,” narrated Bhatti, “I came to know through an employee of the Livestock Department that a survey team had visited this area and marked it for handing it over to the Army.”

“I was shocked as no one in our community knew about it. This is our livelihood, our home for more than 70 years, where do they expect us to go?” asked Bhatti.

‘We have no choice but to resist’

The same news came knocking at the doors of contract farmers of Muhammad Nagar seed farm near Arifwala in district Pakpattan. The Agriculture Department issued a letter in February 2024 telling them that it will be handing over 498 acres of the farm to the Pakistan Army by the end of April 2024.

Days later, the tenant farmers received notices barring them from sowing new crops and warning that anything planted now will be destroyed.

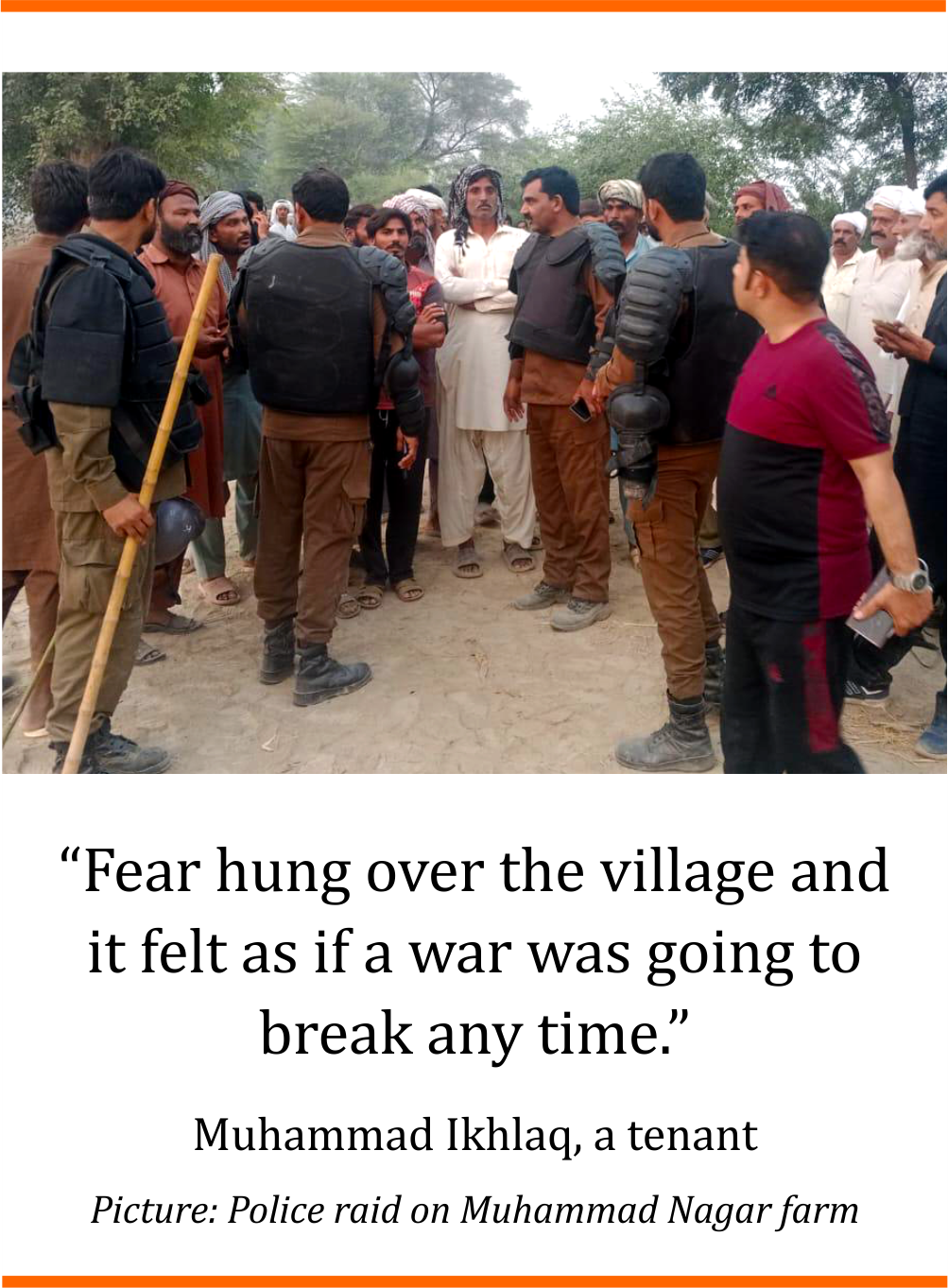

The farmers, however, didn’t stop. “For months, the atmosphere was extremely tense. Fear hung over our village, and it often felt as if a war was going to break at any time,” said Muhammad Ikhlaq, a tenant farmer.

The farmers decided to approach the court. They filed a petition in March 2024 challenging the Punjab government’s order of transferring land to Green Corporate Initiative.

Ghaffar ul Haq, the lawyer representing the tenants, informed Lok Sujag that they have pleaded that if the Punjab government no longer requires land for the seed farm, it should sell it to the tenants who have been working on it since 1928. “The state cannot treat them as temporary occupants when their labor has sustained the farm, and their families, for nearly a century,” said Ghaffar.

The farmers in other areas took the same course. The cases of tenants of Ehsanpur and Rakh Ghulaman are now with the Multan bench of Lahore High Court and of Chak Katora is before the Bahawalpur bench.

The courts provided the farmers with temporary relief by issuing a stay order that barred the government from taking any further action besides the court asked the government to submit its response.

The government, however, is employing delaying tactics. In Muhammad Nagar case, the respondent’s counsel appeared before the Lahore High Court for the first time in June 2025, more than a year after the case was filed, only to seek more time to prepare the case. He repeated the same request at the next hearing in October 2025.

While the farmers welcome temporary relief provided by the court, long delays in court proceedings are making them restless. Their anxieties get a boost at each hearing date. Their growing insecurity is also rooted in a series of unpleasant incidents.

As tenants of Muhammad Nagar seed farm prepared to harvest their crops in November 2024, a large contingent of police backed by prisoner vans, revenue officials, and heavy agriculture machinery arrived at the fields. This happened despite the court having issued a stay order in favor of the tenants.

As the machinery started destroying standing crops, the farmers decided to resist. A tense standoff followed and lasted for two days when eventually the administration decided to move back.

The tenants of Ehsanpur narrated a similar story. “They stop us from sowing or harvesting,” said Hussain, a tenant. “They abuse women, threaten us, and bring the police along.” In April 2025, when these tenants wanted to harvest their wheat, they were arrested and their tractor was seized. Women of these families held a protest and blocked Layyah-Kot Addu highway until the administration was forced to release the detained farmers.

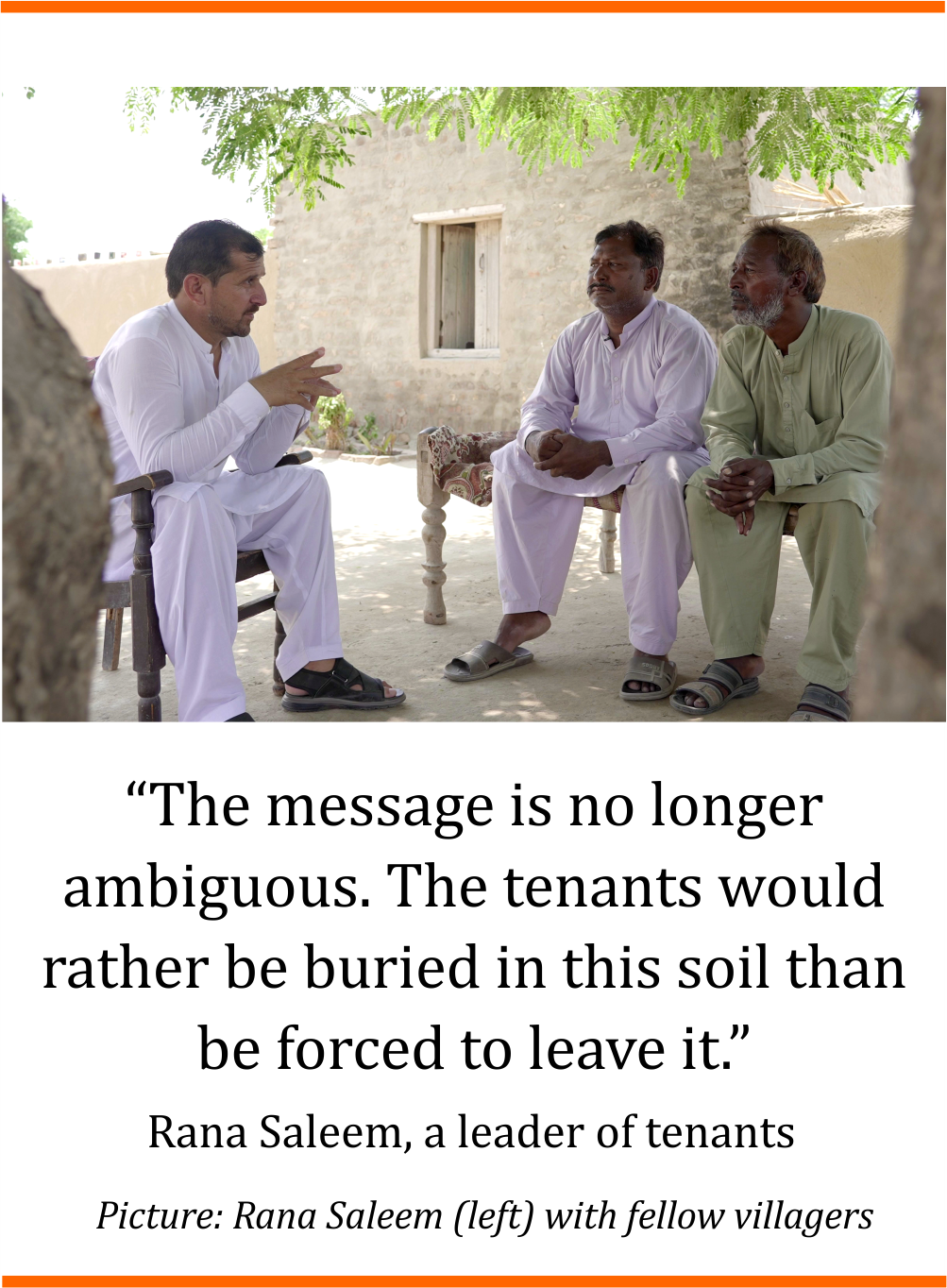

Rana Saleem, a tenant farmer in Rakh Ghulaman is now leading the resistance in his village. He narrated his story to Lok Sujag: “When the officials gathered our villagers and told us we had one week to vacate, I saw 80 and 90 year old men, who had spent their whole lives here, suddenly sit down on the floor. Their legs gave up. They were too stunned to stand. They just looked at each other – bewildered and lost.”

That moment, he says, changed everything. “When I saw this, I knew I had no choice. I have to fight for them, for all of us.”

Till death do us part

It was still early on the morning of May 5, 2025 when the farmers of Rakh Ghulaman were doing what they now excel in - re-strategizing. The district administration had refused them permission to hold a protest at the busy Chandni Chowk intersection on the Bhakkar-Mianwali road, so the organizers scrambled overnight to secure a new site near the village.

By dawn, some men were busy erecting tents on the new site while others were leveling a mound of sand and covering it with rugs to create a stage. As the sun shined, buses and vans began arriving from across Punjab.

In the beginning, the protest felt like an isolated village rally and a localized show of force but it changed as political activists and supporters gathered. Activists from the new left, Huqooq-e-Khalq Party, (People’s Rights Party) joined the gathering led by one of its leaders, Farooq Tariq. The crowd’s energy surged when Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Jr, a scion of the Bhutto family, joined. He travelled all the way from Karachi to stand with the farmers. Everyone converged around a single demand - right to the land that sustains them.

The slogan malki ya moat (ownership or death) resonated with the gathering the most.

The slogan was originally coined by Anjuman Mazarain Punjab (AMP), literally meaning association of tenants of Punjab that was formed in 2000 when the army had tried to change sharecropping contracts with the tenants of military farms in Okara district. The farmers refused to accept new conditions and decided to hold their fort. The tenants’ movement endured a harsh crackdown over the next many years, including mass arrests and charges of high treason against its leaders.

For the farmers gathered at Rakh Ghulaman that day, AMP was less of a formal organization than a shared language of suffering and resistance.

In the months following eviction notices, the tenant groups began organizing their defense under the banner of Anjuman Mazarain Punjab. Muhammad Ikhlaq, a tenant of Muhammad Nagar seed farm is AMP’s General Secretary.

“Farmer’s resolve sharpened after reports of a police operation against tenants of Muhammad Nagar farm in Arifwala,” said Farooq Tariq, who is also General Secretary of the Pakistan Kisaan Rabita Committee, a network of organizations of small farmers and tenants. “We called the affected farmers to Lahore and in that meeting we decided that no one would vacate their land. We will resist.” He terms the leasing of agricultural land to corporate entities a move to place profit ahead of sustainability and social justice.

The protests are continuing from farm to farm with no signs of let up.

Shahnaz Parveen, a tenant farmer of Chak Katora, appeared as resolute in a November 2025 rally in her village as she had been six months ago when we met her for the first time. She moved through the protest ground with dozens of other women, chanting slogans against what they called corporate capture.

Rana Saleem who had travelled from Rakh Ghulaman to join the November rally appeared more confident than before. He said that the movement would pursue its demands on both fronts, through the courts because the farmers believe they are legitimate claimants, and through the streets because silence can only make things worse.

Pointing at the crowd, Rana Saleem said with poise. “The message is no longer ambiguous. The tenants would rather be buried in this soil than be forced to leave it.”

Swapping one deficit with another

Rakh Ghulaman became a bane for the GPI also for a different but related reason when late in February 2025, villagers reported to the police that hundreds of trees on the government-owned land were being cut.

Police records reviewed by Lok Sujag describe that when the officers visited the site on March 1, 2025, they found men openly felling trees. A supervisor on the site informed that the land had been contracted to three men, Ghulam Mustafa, Malik Asim and Muhammad Sultan under the Green Pakistan Initiative and that the contractors were selling the timber to local traders.

He claimed that trees worth millions of rupees had already been cleared. The trees on government lands can only be cut following a set of rules which also makes it mandatory to hold public auctions of the timber. By the time police documented the case, much of the forest had already disappeared.

Rakh Ghulaman was an agroforestry landscape, where livestock rearing, fodder cultivation and tree cover coexisted. Animals grazed in fields planted with rotating fodder crops, while Indian rosewood and silk cotton trees grew in measured rows, offering shade, shelter and a living canopy across the farmland. That balance has been upended.

According to Dr Amir Hayat, an official of the farm, only half (5,000 acres) of the farm area has so far been given to the contractors, significantly, the half with the densest tree cover. Officials estimate this stretch alone had nearly 24,000 trees, but locals insist the number was at least four times higher. Today, most of it has gone and the timber has either been sold or is lying abandoned at the farm. A few piles, seized as evidence, sit at the local police station gathering dust as a stark reminder of what has been lost.

Ghulam Mustafa, one of the investors, insists that he acted legally. He claims that the trees were auctioned by the Livestock Department and that he had won the bid, paid the government, and only then cleared the land and sold the timber to local traders. But the farm’s superintendent, Bakhsheesh Haider, flatly denies that any auction ever took place. No official record of such a process has surfaced.

Mustafa argues that the trees had to be cleared to make way for what he calls modern farming. Precision agriculture on a large scale, he continues, requires installation of central pivot irrigation systems. They demand vast, unobstructed fields to function which means that ‘trees have to be sacrificed at the altar of modern corporate farming’.

A similar sacrificial ritual was reported from Chichawatni, Sahiwal district where 100 acre land reserved for a sub campus of the University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences was instead contracted to one Sadaat Agro Farm Private Limited. Locals say that even after the courts suspended the order, the contractors moved in and cut down the trees. Villagers WhatsApped photographs and messages and lodged complaints with the officials but nothing happened.

The pattern is already spreading. In Rakh Mahni, a government livestock farm also in Bhakkar district, once dotted with small trees and shrubs for camel breeding, the landscape is slowly changing. Of its 9,000 acres, a third has been leased to Green Impex Farm. The neighboring 6,000 acres, though yet to be cultivated, have been taken over by a joint venture between Fatima Fertilizer and the UAE’s Najd Gateway Holding. What was once a public resource for livestock and pastoralists is being remade into a hub for export-oriented fodder, the landscape is slowly changing.

The central pivot irrigation systems are marketed as an efficient alternative to traditional flood irrigation, which loses substantial amounts of water in seepage and evaporation. Environmental experts, however, caution that while central pivots may conserve water, destruction of tree cover is likely to cancel out those gains. Trading one form of sustainability for another and replacing one type of ecological deficit with another makes little sense makes no sense to the experts.

To pivot or not to pivot

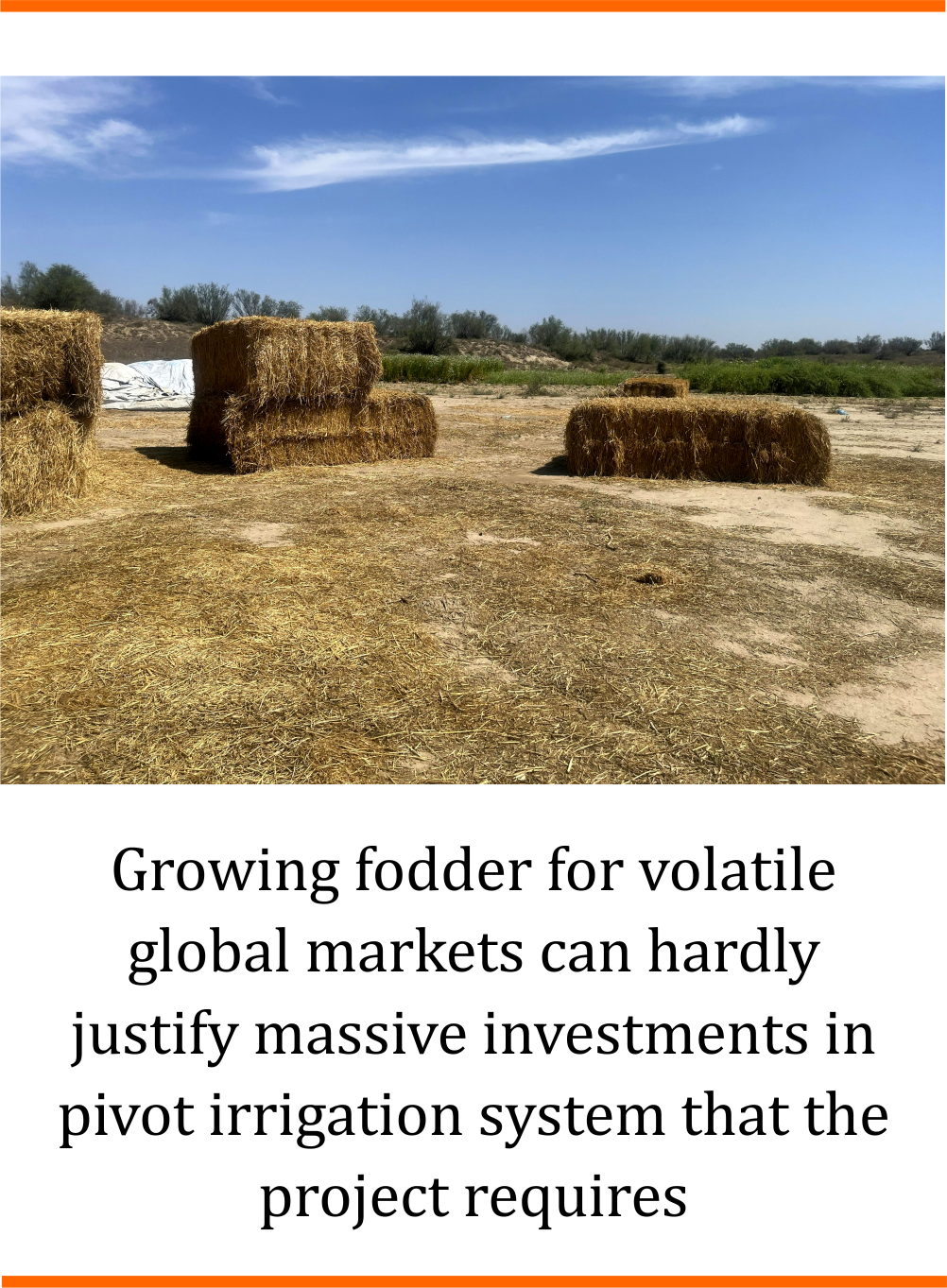

The hidden costs of the new irrigation technology - central pivot system - aside, its upfront financial cost dictates what shall be grown under it. A single unit of central pivot system costs millions of rupees and it is on average good for a 125-acre farm so eight such units are needed for the smallest farm (1000 acres) that the GCI offers to investors.

With such high initial costs, investors obviously prioritize exportable cash crops and not the ones that could directly contribute towards strengthening domestic food security. Fodder crops for exports fit well in investors’ rate of return equations.

A study commissioned in June 2024 by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private-sector arm of the World Bank, identified Rhodes grass as the most lucrative option for corporate farming in Pakistan. Under pivot irrigation, it can yield up to seven harvests a year, making it a prized export to Gulf countries, where it feeds industrial-scale dairy and livestock farms. The IFC report hailed Rhodes as the fastest-paying investment in Pakistan’s corporate farming sector, with payback periods as short as five years.

But five years may not prove to be a short period for volatile and eventful international markets. The IFC report also pointed to Sudan as both a model and a warning for Pakistan. For years, Sudan’s climate and water resources made it a leading supplier of Rhodes and alfalfa to the UAE. But when civil war erupted in 2023, production collapsed almost overnight, leaving Gulf states scrambling to secure new sources of fodder.

Pakistan, the IFC suggested, could step in as a natural replacement, with its vast land reserves and favorable climate offering the scale that Gulf markets demand. Yet the risks are hard to ignore as heavy investment in high-cost pivot infrastructure ties the investors to a fragile global market. If Sudan stabilizes and re-enters the trade, fodder prices could tumble, leaving Pakistan’s ventures stranded.

The central pivot systems are now locally manufactured in Pakistan, by Heavy Industries Taxila (HIT), which is a part of the military’s industrial complex. The HIT frames this effort as its contribution to the national cause of food security. Its first indigenously built system is already operational on a 50 acres farm in Bahawalpur, and according to its website the factory is now mass producing 50 units.

Back to Rakh Ghulaman, a senior official visited the tenants in June 2025. Rana Saleem informed us that the official came up with a new proposal, “Don’t leave. Continue farming. But let us install central pivot irrigation systems. And from now on, pay your rent not to the Punjab government but to the Army.”

It sounded like a compromise but made no sense to the farmers.

Months later in October 2025, members of the AMP got similar vibes when they were invited for a meeting with the higher officials related to the project. Saleem recalls, “The officials assured us that they did not want to uproot farmers from their homes or fields. They also made a conditional offer - if the Punjab government grants ownership rights to the tenants, they [GCI] would not oppose it but if it does not, the farmers should ‘join’ the Green Corporate Initiative’s agenda to modernize agriculture.”

The offer has only deepened uncertainty among the tenants. “How will a system designed for industrial-scale farming work here?” asked Rana Saleem. A pivot machine is designed for mono-cropping over 125 acres. Most of these tenants hold just 4 to 5 acres.

“Will they combine our small plots and ask all of us to sow the same crop? Who decides and who would control the machine? And why should we pay rent to anyone anymore? We are clear that we want ownership rights.”

The tenants are resolute that malki (ownership) and not the central pivot system is the way forward for them but the Green Pakistan Initiative still needs to discover a new pivot to sustain itself.

This feature was produced as part of the Bertha Challenge Fellowship.

Editor: Tahir Mehdi

Research Assistance: Abdullah Cheema, Kaleemullah

Graphics and Design: Shoaib Tariq, Mohsin Muddasar

Pictures: Sumaira Aslam

Published on 10 Jan 2026