If you go southeast of Mingora, the main city of Swat Valley, you will come across the small town of Islampur, 11km away. This village, located at the foot of the mountains, has been there since ancient times but in the last 25 years, it has become a wonderful example of cottage industry and a major centre for the production and sale of Swati shawls.

Weaving and embroidering shawls is an old craft here but now it is no longer just a tradition and identity of the valley but a source of economic support for thousands of families.

Thirty-six years old Shumaila Bibi, a resident of Charbagh tehsil, 30km north of Islampur, has been doing embroidery on shawls for three years. She is not educated but earns enough to provide for her family and children. She says that her husband is a farmer who cultivates wheat, peas, onions, turnips and greens in his two fields (12 kanals). The income from these fields used to support Shumaila’s family but the 2022 floods destroyed both of them.

She says that when it became difficult to run the household in the face of inflation, she started embroidery on shawls. She travels two-and-a-half hours every week to buy shawls from shopkeepers in Islampur, not only for herself, but also for the 20 girls in the village who work with her. She charges these girls Rs50 to Rs100 per shawl in return of bringing the order and the remuneration money, which covers her travel expenses and also generates some additional income.

Small earnings, big dividends

The flood did not only destroy the farmers’ fields, it also swept away many homes. First, due to coronavirus and then the floods, the income of millions of people was severely affected. This was the time when many women in Swat made needlework a source of livelihood.

Hafsa Khanum, a resident of Barthana village in Matta tehsil (Upper Swat), says that her house was completely destroyed in the flood and she was on the verge of starvation. Some women in the village used to do embroidery on sheets. On getting inspiration from them, she also started working. With this income, she first bought some household utensils and is now also helping to meet household expenses. According to her, it is not easy to take time out from her household chores to embroider, but this work has saved her from dependence on others.

Women of Swat used to do embroidery earlier, but changing weather conditions, recurring floods, economic pressure and the demand for Swati shawls have combined to change the situation. Women are now not only supporting their families, but are also learning to stand on their own feet.

Shaheen Bibi, a resident of Islampur, is also involved in embroidery on shawls. She says that in 2019, only 15 women worked with her, but now dozens of women from across the district are associated with her. Women from Upper Swat also take up the work. She says that many women had started embroidery work in 2020 after the pandemic, but their number increased significantly after the floods (2022).

"Shawl-making has made women independent, most of us do not take expenses from our husbands, but rather are sharing the burden of the house."

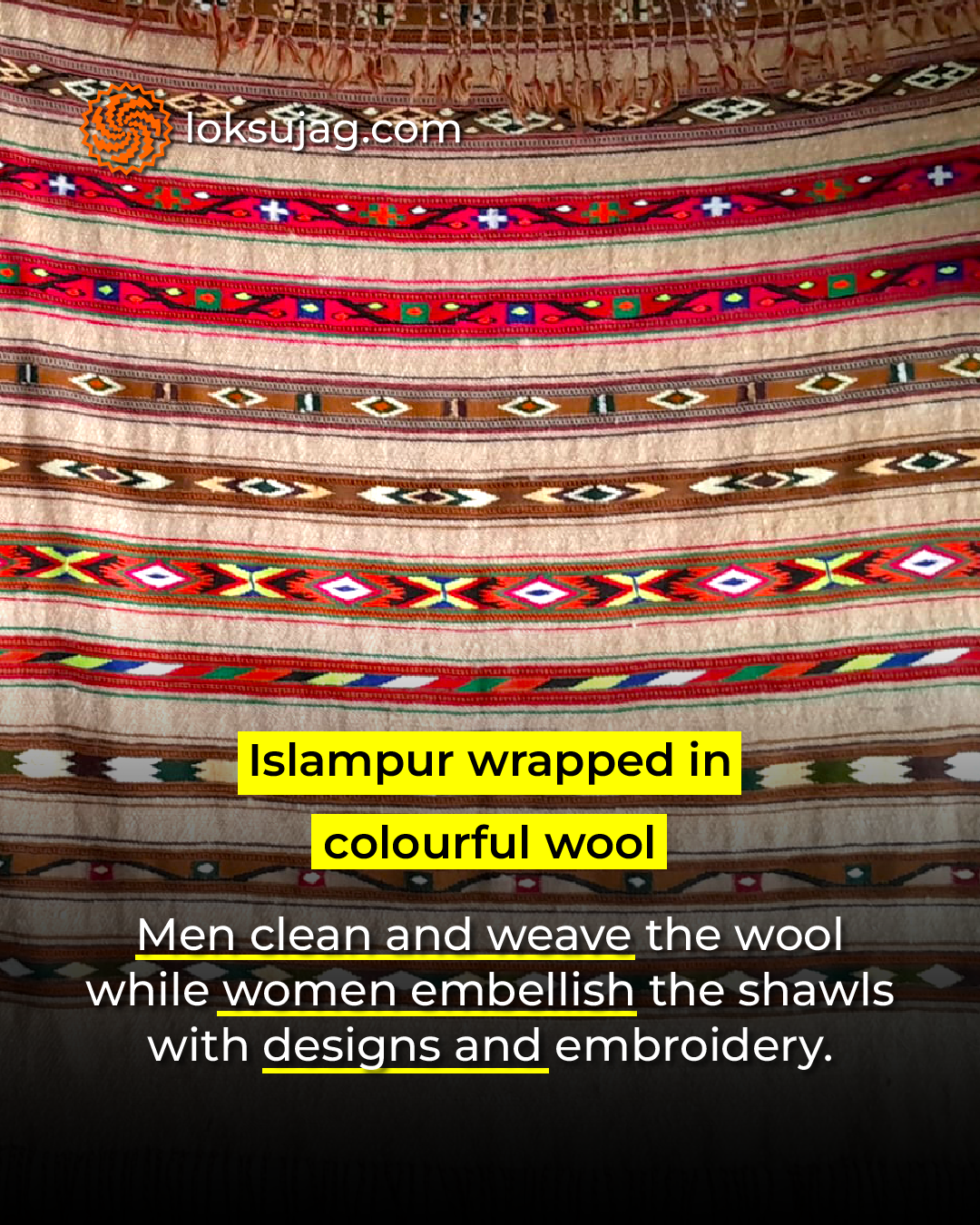

Clatter of looms and colours of wool transforming Islampur

The streets of Islampur are filled with the clatter of looms (powerlooms) everywhere, along with the smell of wool, and the sound of colourful woolen threads hanging on the wires (for drying). Of the approximately 2,500 households, more than 80pc are involved in various stages of shawl-making.

Local traders claim that ancient Hindu and Buddhist engravings and paintings can still be found on stones and wood around Islampur, which are also reflected on modern shawls. According to them, in the olden days, the kings and maharajas of the subcontinent used to order shawls from here and this tradition continues.

Currently, around 90 units (or workshops) are operating in Islampur, consisting of traditional looms (powerlooms) and new machines. Among them, more than 20,000 skilled workers from other areas clean, dye, spin threads and weave the shawls. Shawls are completely hand-made. The stages from cleaning the wool to weaving are generally handled by men while women decorate the shawls by designing and embroidering them at home.

The most popular embroidery styles here are Astari Phool, Mukhi Phool, Ganda Galli, Sindh Yan, Taweez Gali, Brigitte Galley, Do Sooti and Ghota Phool.

Local shopkeeper Muhammad Hafeezur Rehman says that the number of women embroidering increased in 2010 (this was after the Taliban occupation of Swat, the operation and the first major flood of this century). “With the increasing use of social media, more women came to this work.

These events (military operation and floods) affected thousands of families. Due to cultural issues, women cannot work outside, so they are forced to do embroidery at home.”

Rehman says that some traders here also get embroidery done by women from Dera Ismail Khan, Haripur, Multan and other areas but embroidery of Swat is more preferred. Women are the backbone of this entire system, he adds.

How much does a woman earn from embroidery?

Shaheen Bibi says that women are paid based on the quality of work and the number of flowers on the shawl. Gents shawls have a specific type of short embroidery while ladies shawls have it more with multiple types of flowers. Women who do not embroider flowers neatly get paid less while women who embroider well earn more.

She says that in the market, the wages for embroidering flowers are usually between Rs300 and 3,500 per shawl, depending on the work. If a buyer wants to get a special design made, that work is given only to expert women, the payment increases.

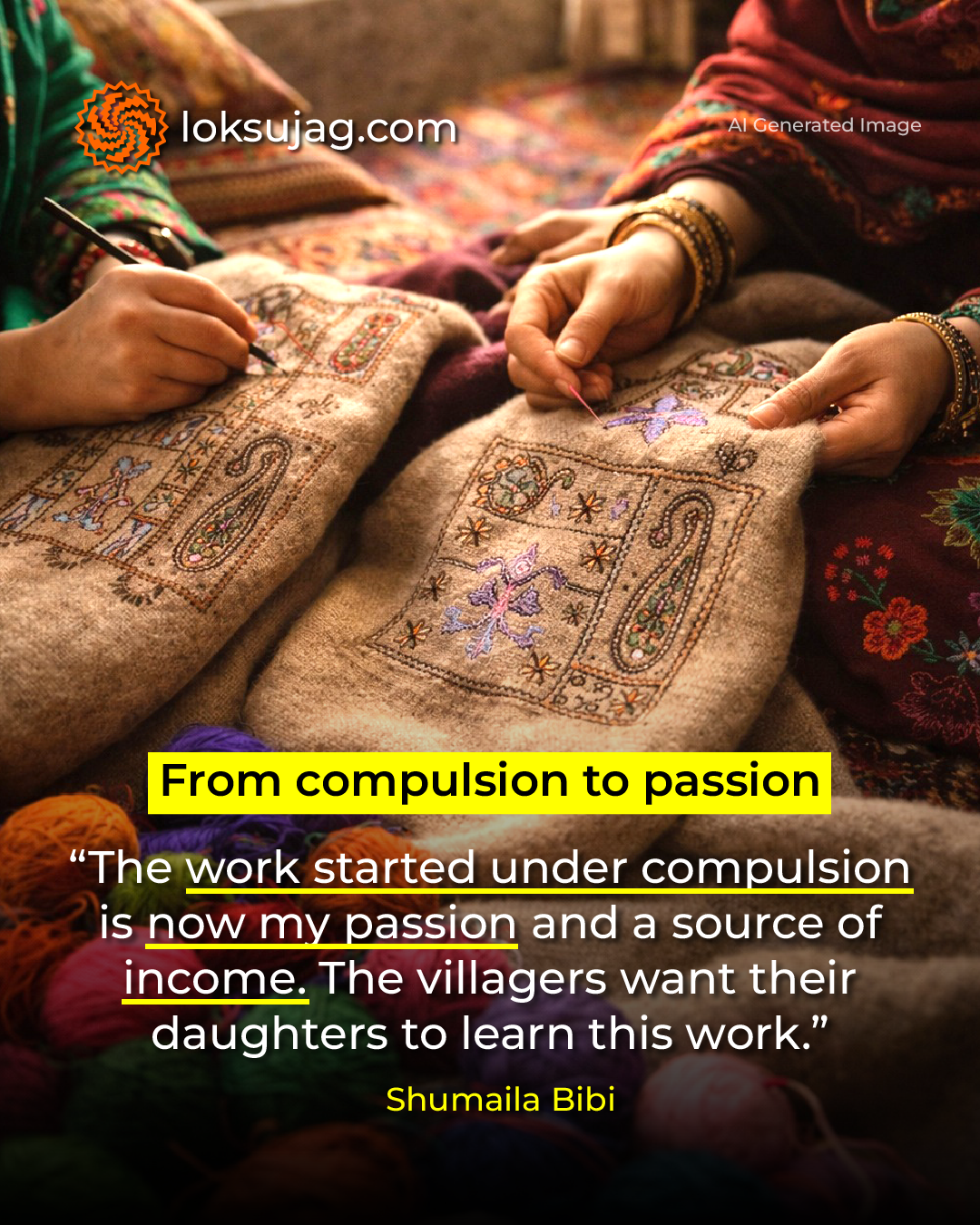

Shumaila Bibi says that since she makes flowers immaculately, she gets paid more, which is Rs3,000-3,500 per shawl. If she has more time, she takes two days for a shawl; otherwise, it takes three days. “The work I started under compulsion is now my hobby and source of income. My family fully supports me and the villagers also want their daughters to learn this work,” she adds.

According to Hafsa Bibi, she does not know how to do very complex embroidery, so she gets a low pay (Rs700) per shawl. Due to her household chores, she can complete a shawl in four or five days, but if she gets a needle wound on her hand, it can take even longer.

“I do not go to Islampur myself, I order shawls from the women of the neighboring village and pay them Rs200 as rent. Once or twice a week, these women come and take the shawls and give her new ones.”

When eyesight fails, women take up related work

Shaheen Bibi says that some women do not know how to embroider or weave well, or their eyesight is weak are given the job of making bombalak (tying the threads that come out on both sides of the shawl by twisting them). Necessities have also pushed older women to work day and night.

Sixty-year-old Zahida Bibi says that her daughters-in-law do the housework, so she makes 15/20 bombalaks, for which she gets Rs15 per shawl. With this money, her personal needs are met, and she does not have to look towards her children or husband for support. It means this woman can’t earn more than Rs600 per day on average.

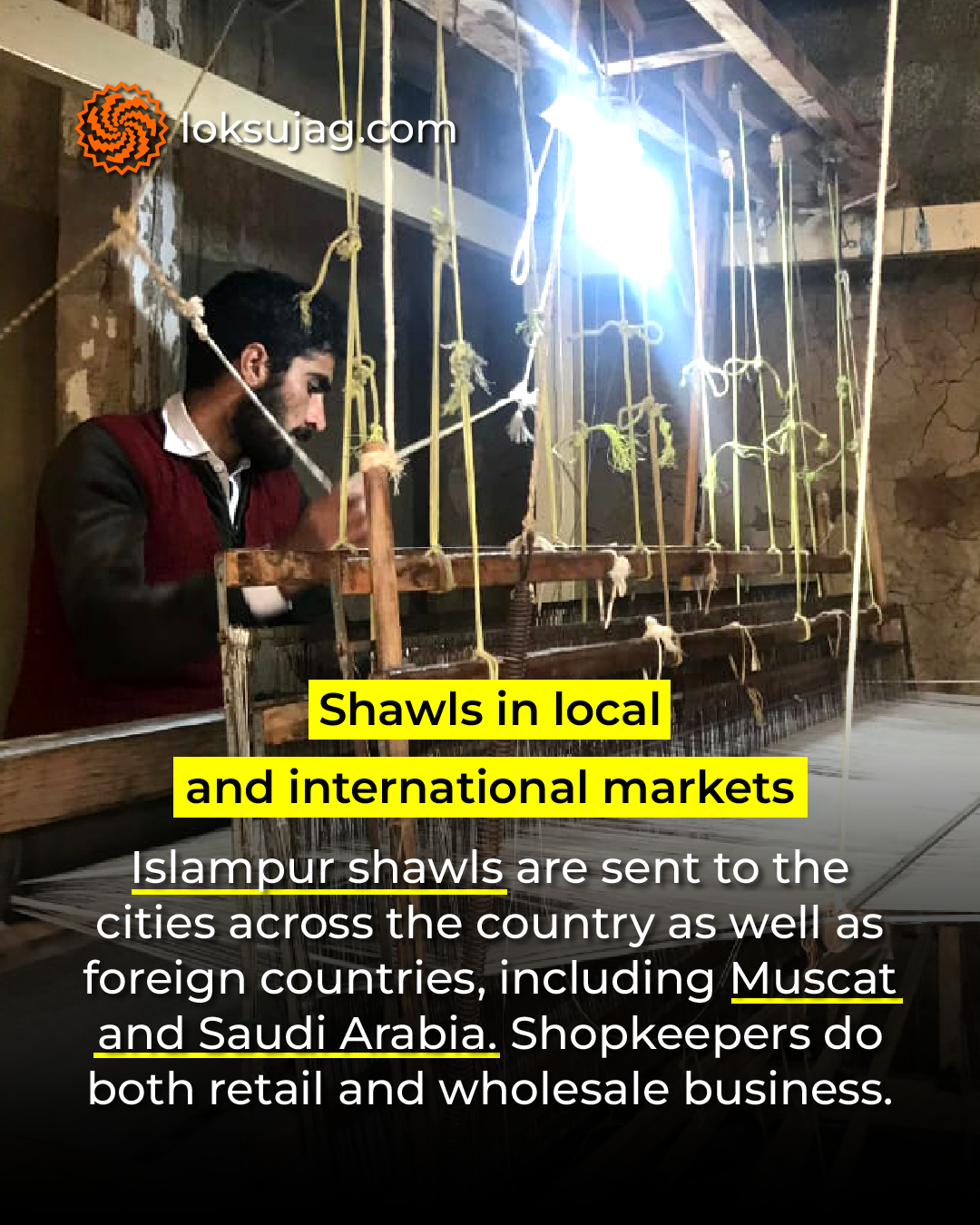

Swati shawls from the Islampur market go to various cities across Pakistan as well as to many countries, including Muscat and Saudi Arabia. The shopkeepers here do both retail and wholesale business of shawls.

Muhammad Hafeezur Rehman says that Chinese, Australian and local wools are used in making shawls in Islampur. From the Swat Chamber of Commerce and Industry to the organizations working for the promotion of handicrafts, no one has any reliable data on the volume of business being done in the Islampur market annually.

No one can even tell the exact number of women who are working in the cottage industry here and making woolen shawls attractive and beautiful.

According to local traders, men’s Swati shawls are sold for 10,000 and women’s for 30,000.

However, an average plain shawl in the market is available for about Rs2,000. After embroidery and bombalak, this same shawl sells for Rs5,000 to 6,000, but for a woman gives this work her life earns only Rs600 to 700.

Published on 13 Feb 2026