Salma Bibi, a resident of Sultanwala village in Mianwali, tied the knot outside her family 15 years ago. Today, she is a mother of three children, all actively engaged in their studies. The family grapples with financial constraints stemming from her husband’s modest income.

A few years back, Salma Bibi’s father passed away, leaving behind approximately 12 acres of agricultural land for his two sons and a daughter. However, even after three years, Salma finds herself as the ‘nominal’ owner of the land, navigating the intricacies of this unexpected situation.

She says that about 19 kanals of her share of land is being used by her brothers.

“Until now, I have neither the land nor a share of the harvest income. My brothers refuse in case I ask for my share. If I go to court, we will all be defamed, so I’m quiet.”

Similarly, the inherited land of 58-year-old Kaniz Fatima, a resident of Wan Bhachran, is also with her brothers. Her children have grown up, but she never asked her brothers about their father’s land, nor has anyone ever told her.

She points out that the tradition of granting a share of property to sisters or daughters is nonexistent here. While the land may be registered in their names, it effectively stays under the brothers’ control.

“Our mothers and grandmothers were also deprived of inherited property. The land had come to my share. But I am silent so as not to cause a rift in the dear relationship of brothers and sisters for the land.”

According to prevailing Islamic principles, a daughter is entitled to half the inheritance of a son. This right was recognised in the Muslim Personal Law Application Act of 1937, before the creation of Pakistan. It was later upheld in the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance in 1961 and 1964.

Article 23 of the Constitution of Pakistan guarantees every citizen the right to property (without discrimination of sex). The laws of the country and several judgements of the High Courts also protect the right of women to inherit. Yet many women are being deprived of property.

To keep women from inheriting, the backward patriarchal society had ‘invented’ many methods and customs centuries ago. Foremost among them was ‘marriage to the Qur’an’. Women’s property is often transferred to the brothers in watta satta (bride exchange), Swara, or Vani marriages.

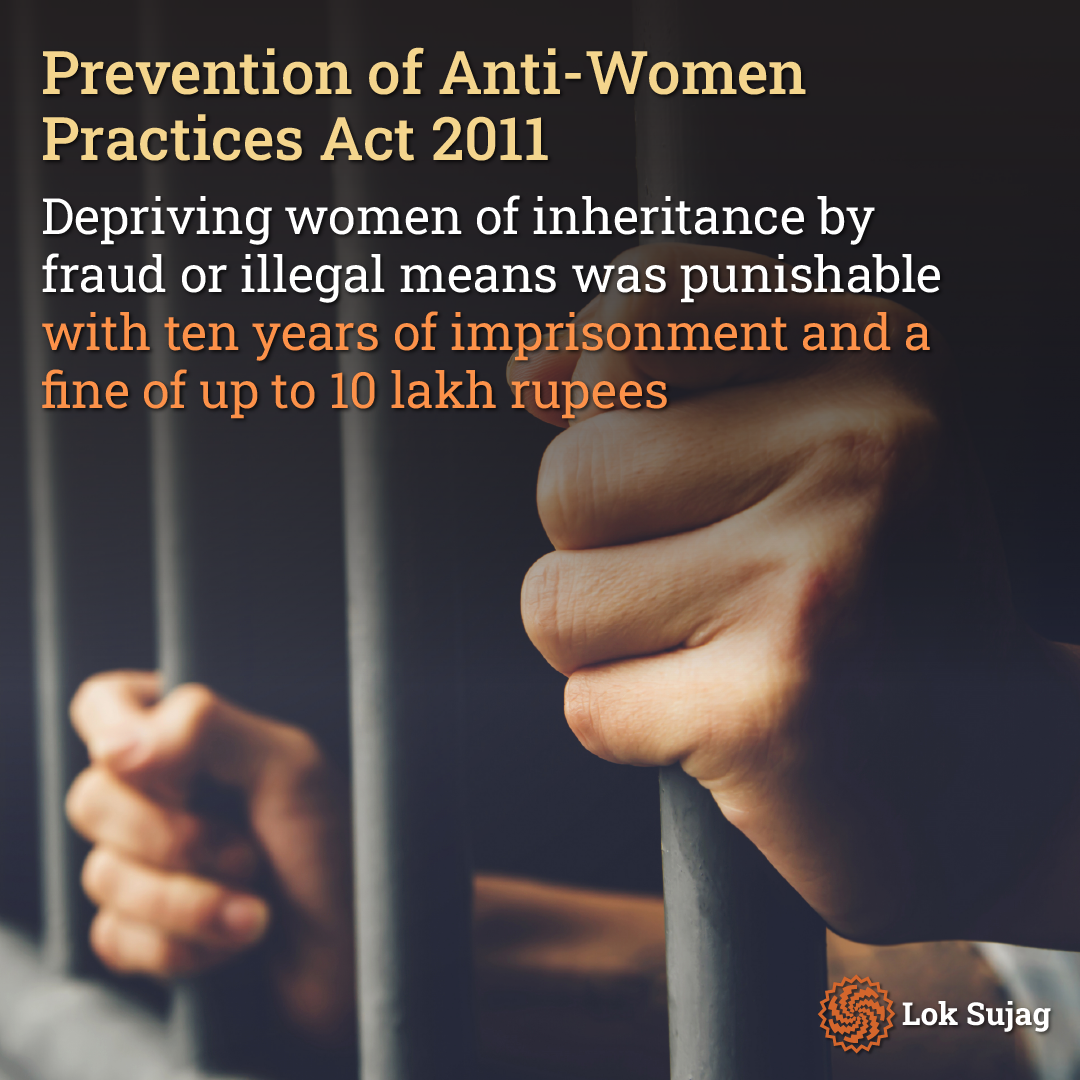

In 2011, the Prevention of Anti-Women Practises (Prevention of Anti-Women Practises) Act was passed to end this trend. Under Section 498-A, the punishment for depriving women of inheritance by fraud or illegal means was fixed at imprisonment for ten years and a fine of up to 10 lakh rupees.

But the process of grabbing the inherited property of women has not stopped.

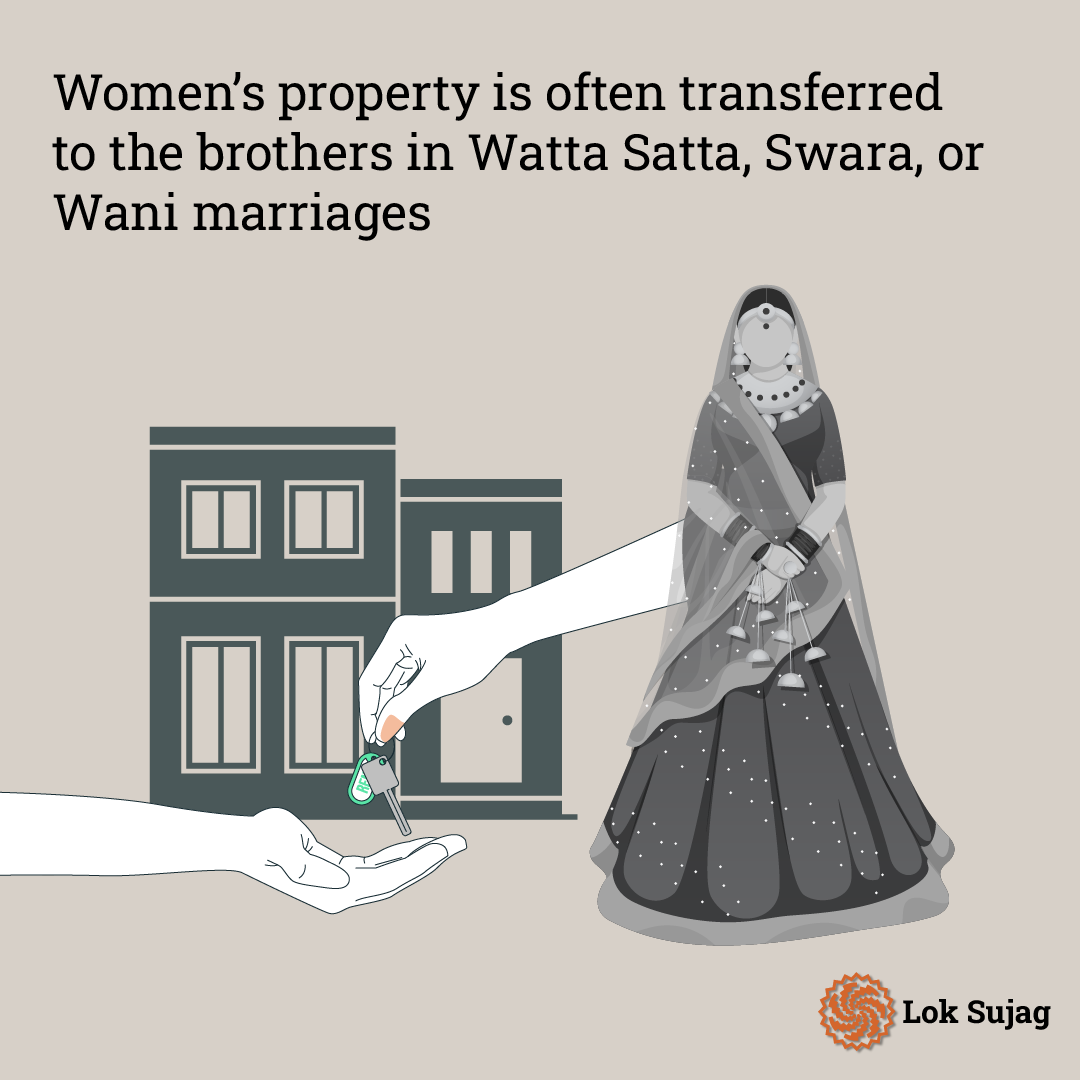

According to the Punjab Gender Parity Report (PGPR) 2021, the number of land owners in Punjab is around two crores and 60 lakhs. Of them, one crore, 77 lakh men and around 81 lakh women are landowners. This rate is 69 and 31 per cent, respectively.

In 2021, inheritance property was transferred to more than 23 lakh people. However, the ratio of legal heirs shows gender equality, where 11 lakh 57 thousand men (50.3 per cent) and 11 lakh 43 thousand women (49.7 per cent) received inherited property.

The digitisation of land records due to the amended Punjab Land Revenue Act 2012 and 2015 has positively protected the land rights of senior citizens and women.

District-wise data highlights the gender disparity among landowners in different districts of Punjab.

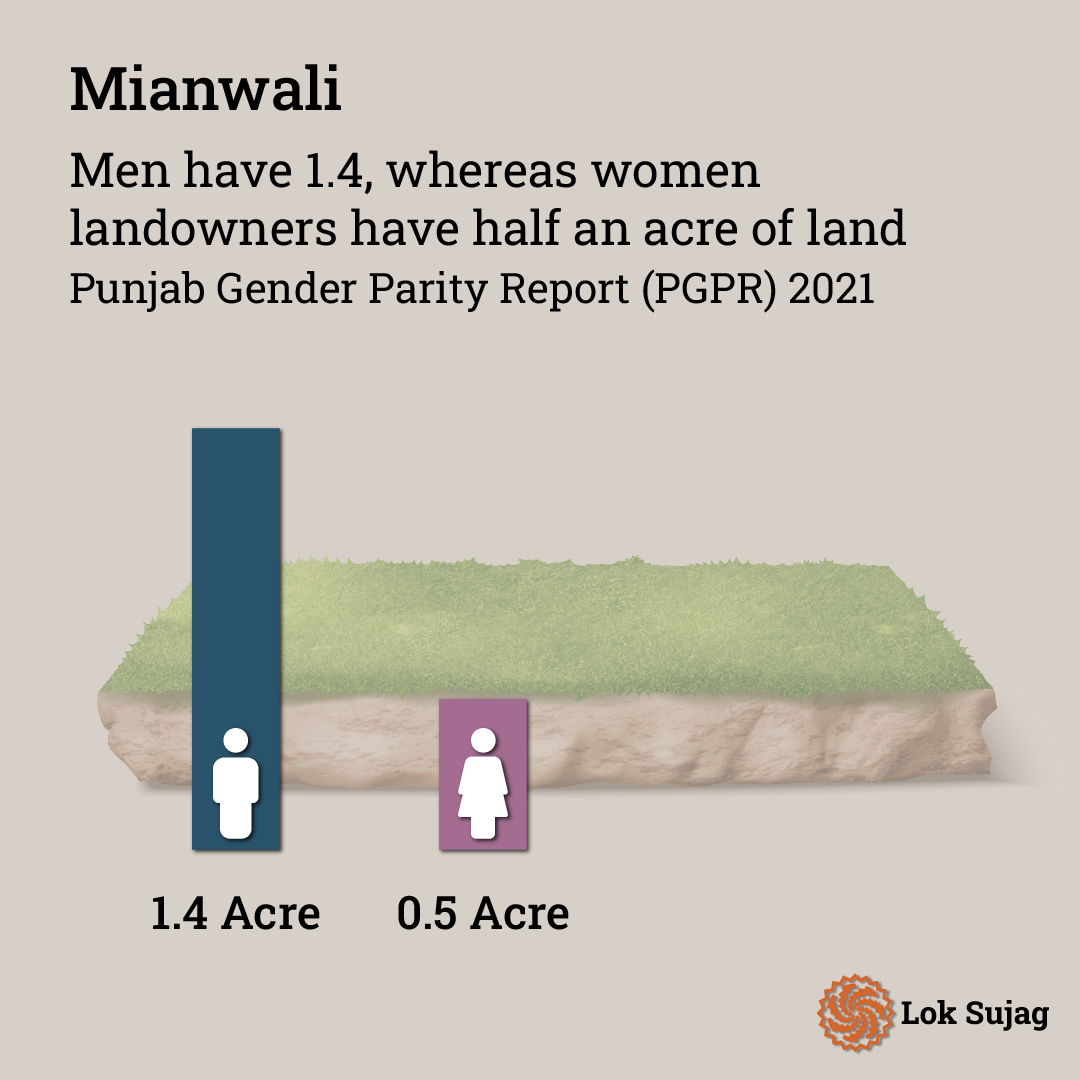

According to the report, the average land owned by men in Khushab is 3.2 acres, compared to 0.9 acres per capita owned by women. In Mianwali, men own one-tenth and women landowners own about half an acre of land on average.

Contrary to statistics, in most cases, women’s ownership is limited to documents.

After Khushab, Mianwali is the second district of the province where the difference in ownership between men and women is the highest. There is no change in people’s behaviour in this regard.

Tehsildar (revenue officer) Abdul Rasheed, posted here, confirms that in Mianwali, inheritance is transferred to women according to the procedure and law, but brothers usually use this land.

District Bar Association Mianwali official Babar Khan believes there are loopholes in the Act to prevent anti-women behaviour, which is why the problems persist. The Act does not define ‘fraud’ and ‘unlawful practise’.

He says the law does not clarify whether emotional blackmail and “persuasion” also fall under illegal methods. Often, women are disinherited through emotions or persuasion.

Irfan Khan, in charge of judicial complexes of women’s inheritance cases in Mianwali courts, said that on May 9, the complex was set on fire, burning the records and IT rooms. So, it is impossible to provide data.

Also Read

Inheriting inequality: The long struggle of a Hindu woman to inherit her ancestral property

However, according to the Benazir Centre for Women’s Rights (Women’s Crisis Centre) data in Mianwali, 13 complaints by women were registered for property this year. Five have gotten a share of the property under the court order. The cases of others are pending.

Samira Siddiqui, a social welfare officer posted at the crisis centre, says that very few women come to the centre with complaints. The majority are not aware of their rights; the main reason for this is the lack of education among women. If a woman comes, the institution arranges legal assistance from the government.

Amara Niazi, a Women’s Protection Committee member, says it is common for women not to have a share in inheritance here. Most women do not ask for a share because of family marriages. Even if the inheritance is transferred to the name of these women, they do not claim their right over it.

Religious scholar Qari Zafar Iqbal says that the people of Mianwali do not consider anyone to be their equivalent in the matter of honour.

“But I don’t know where our honour goes when we are taking away the rights of our sisters and daughters. We have neither fear of law nor fear of God.”

Published on 1 Dec 2023