Munir Ahmed stares out at what was once a thriving 10-acre guava orchard in tehsil Sharaqpur of district Sheikhupura. Now, it’s a wasteland of silt and stagnant water. Just months ago, he had leased the land and invested around a million rupees on nurturing the fruits. His hopes for a good harvest that would have allowed him to feed his family for the coming months have been completely washed away.

“The flood has destroyed everything,” Munir says, the despair evident in his voice. “I am now looking at a loss of between Rs2.5 million and 3 million.” Like many farmers who don’t own their land, Munir’s investment was financed through debt. “I had taken a loan from a fruit supplier in Timergara, Lower Dir, and that debt has now become a burden. We cannot buy the seed for next crop. We cannot afford to buy it if we have no money.”

He had also leased 20 acres of land to plant sorghum, maize and rice, which has also been destroyed in the floods, causing about Rs5 million losses. While the rivers may have calmed down a crisis of survival is just beginning for farmers like Munir.

Munir’s story is one of thousands of farmers across Punjab where the scale of destruction is at a level not seen in more than three-and-a-half decades, since the disastrous floods of 1988. According to the preliminary Flood Loss Assessment Report of the Crop Reporting Service Punjab released in the late September, nearly 2.5m acres of farmland have been damaged, destroying the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of people.

Floods destroyed half of vegetable fields

This year’s floods have hit vegetable crops the hardest, with the damage estimated at 44% (51,000 acres) of the total cropped area (115000 acres) in Punjab. Enormous damage has been inflicted on the epicenter of the province’s vegetable production, with the divisions of Lahore, Sahiwal, and Faisalabad losing 175,000, 177,000, and 492,000 acres of total cropland, respectively. This widespread damage has directly affected key vegetable producing districts, including Pakpattan, Kasur, and Sheikhupura, which will result in a significant decrease in the supply of fresh produce to urban centres across the country.

The district of Sheikhupura, a major agricultural area due to its closeness to the market of Lahore, faced the Ravi River’s fury directly. In Sharaqpur, where Munir Ahmed lives, the river surged nearly 5km inland, submerging numerous villages and their farmland. The farmers here often cultivate vegetables alongside their main crops of rice and orchards to meet urban demand in Lahore.

Malik Jahangir Manzoor, a farmer from Bholay Shah in Sharaqpur tehsil, had his crops of ladyfinger, ridge gourd, potatoes and bottle gourd completely wiped out by the flood. “These vegetables were going to the market every day and prices were low. Now, the prices have all shot up,” he says.

“I had planted ladyfinger, ridge gourd and bottle gourd, and spent Rs100,000 per acre on them,” says Abdul Sattar, a farmer from the neighbouring Faizpur Kalan. His story is the same as that of Jahangir.

A major factor behind the damage was the timing. According to Ghazanfar Hammad, a principal scientist at the Vegetable Research Institute in Faisalabad, says the floods struck just when summer vegetables, such as ladyfinger, bitter gourd and round gourd, were being harvested. This immediately caused a huge spike in prices. In the last week of August this year, prices of Kharif vegetables were significantly higher than last year. Ladyfinger, bitter gourd, bottle gourd, and watermelon saw a 98pc, 87pc, 55pc, and 36pc increase, respectively.

Consumers in Lahore are facing price hikes due to decreasing supplies of essential vegetables, a direct consequence of floods that devastated farmlands and severed supply chains. The crisis is hitting both vendors and households, with no short-term relief in sight.

The disruption is clearly visible in Lahore’s main fruit and vegetable market. Muhammad Farman, a vegetable vendor at the Ravi Road market, says that bitter gourd, which used to be sourced from flood-hit areas like Shakargarh and Narowal, now has to be brought in from Sindh, doubling transportation costs.

“Before the floods, bitter gourd sold for Rs500-600 per 5kg. Now its rate is Rs1,000–1,200,” Farman explained. “Our sales have dropped, and the public is also suffering.”

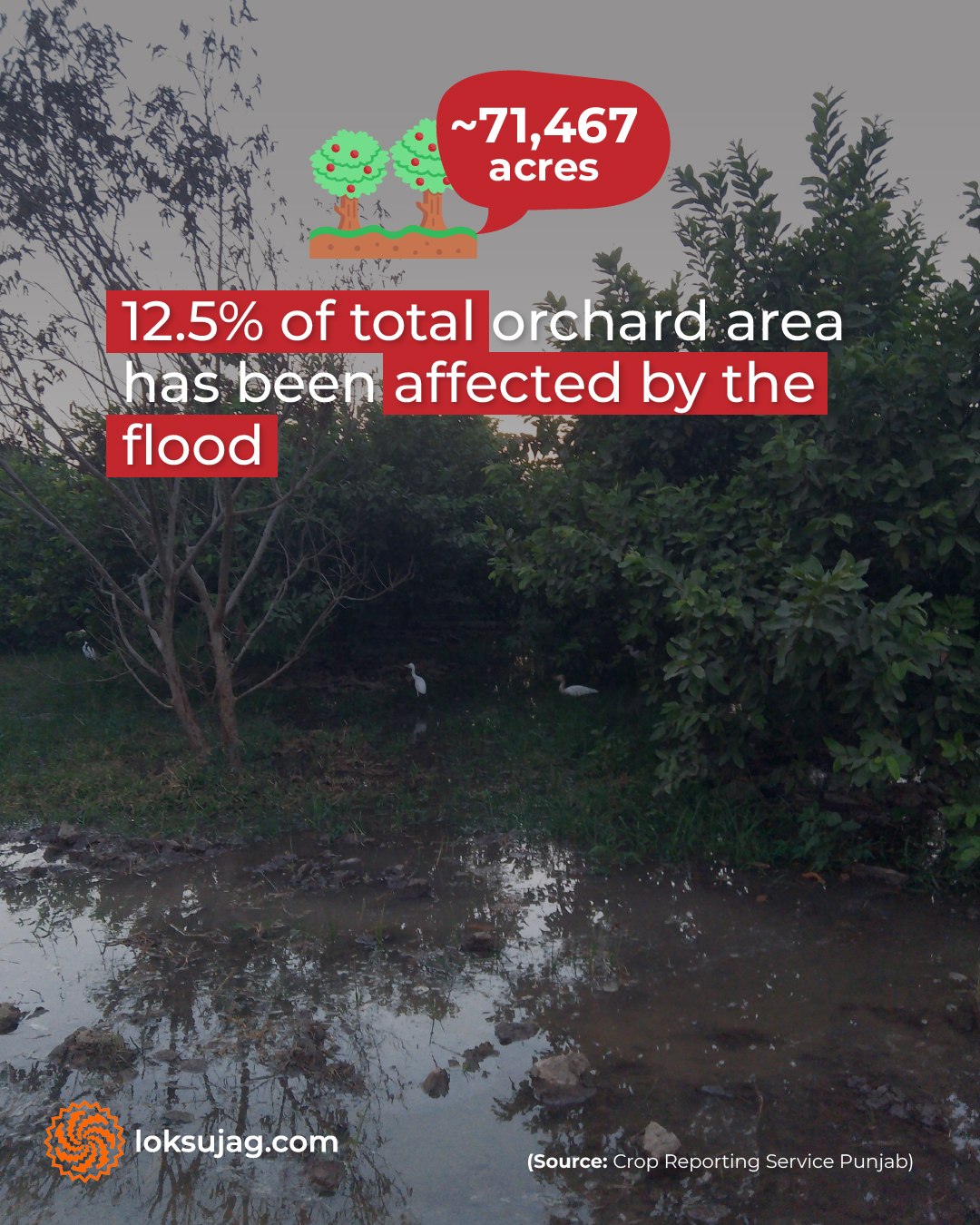

Orchard may take longer to recover

Beyond the annual vegetable crops, the floods have inflicted long-lasting damage on Punjab’s orchards. An estimated 71,467 acres of orchards—12.5% of total orchard area—have been affected by the flood across the province, according to the Crop Reporting Service Punjab. Of this, 64,480 acres are mango orchards. The Multan Division has been hit the hardest, with 38,355 acres of its mango orchards inundated. There have also been significant impacts on other fruits like pomegranates and guavas.

Sheikhupura and Nankana Sahib districts have 28,000 acres of guava orchards, and account for 41pc of Punjab’s total guava production. Sheikhupura alone produces 29pc of Punjab’s guavas. These districts are among those badly hit by the flood and the wholesale prices for guavas in September this year are 21pc higher than the corresponding month last year.

In Munir’s orchard, fruits have shriveled up and blackened while Salamat Ali, another farmer, laments: “I had two acres of orchards, which I had leased for Rs250,000 per acre, and the expenditure of the orchard was more than Rs100,000 per acre. I have lost around Rs0.8m.”

Numerous farmers like him, whose lands were in low-lying areas, have no idea how they are going to survive.

In Muzaffargarh, one of the largest mango-producing districts of Pakistan, Habibur Rehman, the deputy director of agriculture department, says 14,000 acres of orchards are submerged, with 80pc of the trees being three to four years old that will have a zero or near-zero percent chance of survival.

Javed Iqbal, a senior scientist at the Mango Research Station in Shujabad, says standing water creates an ideal environment for soil-borne fungal diseases and pathogens to attack the weakened roots and the tree's bark at the waterline. Even after the water recedes, fungal and pathogen attacks can still damage trees and it requires proper pesticides and antifungal sprays, and fertilizer use to bring the trees back to full health, he adds.

This represents a major blow to Pakistan’s mango and fruit production that will harm thousands of farmers and will take years to recover from. Unlike a vegetable crop, which can be replanted in a season, a mango orchard takes four to five years to regrow and start producing fruit, and almost eight years to reach maximum yield, according to Javed. Similarly, a guava plant takes two to three years to start producing fruit and eight to ten years to reach maximum yield.

The looming crisis of inflation and hoarding

The economic fallout from this year’s flood is expected to be severe. It is likely to create a supply gap that will last for months and result in a manifold increase in prices, according to Muhammad Sajjad Saeed of the Vegetable Research Institute, Faisalabad.

The flooding has also created a long-term obstacle for farmers. Malik Jahangir explains, “Our low-lying areas have five to six feet of silt deposited in the fields, with standing water still present. I doubt the next crop will be planted there at all.”

This damage threatens the sowing schedule for key Rabi season vegetables—such as carrots, radishes, turnips, spinach, coriander, and onions. As a result, these crops will likely be planted late, leading to diminished yields, or they may not be planted at all this season.

Sajjad says the full recovery for vegetables will take two to three years as the flood has deposited layers of silt and sand across vast swathes of land. It could take up to two to three years to clear this out and make the land cultivable again, which will have long-term effects on soil health and yields that affect farmers the most, while timelines for orchard recovery are even longer.

Besides yield and prices issue, there is a lurking danger of hoarding. Aamer Hayat Bhandara, a progressive farmer from Pakpattan district, cautions against hoarding.

“We also need to look at how market factors are playing this and whether or not a shortage is being artificially created.” For him, the main question now is whether the waters will recede in time for the Rabi crops to be planted - a factor upon which the fate of millions of farmers depends.

A long path to recovery

In the face of this enormous challenge, agricultural experts suggest a multi-pronged approach focused on immediate drainage, soil reclamation, and adaptive farming. The single most important step right now is to pump water out of the fields and orchards so that the damage from waterlogging can be minimised and recovery efforts can be started but most farmers do not have the resources to do so.

The government must launch a large-scale programme to provide farmers with gypsum, potassium, and sulphate, which, according to Ghazanfar Hammad, help in repairing the damaged soil. While the soil recovers, he further suggests, vegetable farmers can plant short-term, water-tolerant plants like moong bean or leafy vegetables to generate some income and improve soil health. Water-loving plants like cocoyam (Arvi) are also a wise choice in this situation.

The scientist also suggests the use of raised bed nurseries and drip irrigation to avoid overwatering of plants. Offseason crops, like tomatoes and watermelons, can also be planted to utilise the field conditions, he says, and these strategies can help minimise the long-term economic issues for the farmers who are unable to plant their usual crops.

For orchards, Javed Iqbal of Mango Research Station, suggests that replantation of trees can start four to five weeks after floodwaters recede but recovery from floods will take a significant time as water and silt seep into the soil and stop the healthy growth of trees. This means that new plantations will require substantial financial investment from the farmers in the form of water-draining machinery, fertilisers, pesticides, and fungicides but many of them lack such resources.

The compensation that’s not enough

The Punjab government has announced a compensation package of Rs20,000 per acre for submerged farmland, Rs50,000 for each goat or sheep lost, Rs500,000 for each head of large cattle that perished in the flood.

Director General of Agricultural Information, Naveed Asmat Kahloon, further detailed the ongoing damage assessment. He states that more than 2,000 teams are currently deployed in the field to evaluate the devastation. These teams are tasked with compiling a detailed report on the scale of impact, including the total acres of land submerged, houses destroyed, and livestock lost.

Farmers say that the compensation announced by the Punjab government is nowhere close to what they need to plant next season’s crops and fix the damage to their land.

“With Rs20,000, we can’t even manage the sowing for one acre. What will we do with 20,000?” laments Munir Ahmed, a sentiment shared by other farmers like him who have borne huge financial losses.

Those in the urban heartland may perceive the floods to be over but for the farmers, the troubles have only just started and the urban consumers may feel the crunch in the coming months.

Published on 9 Oct 2025