The ‘Grapes of Chaman’ are famous all over the country. When someone seeks good grapes in the market, they often ask the shopkeeper for ‘Sundar Khani’ grapes from Chaman. These grapes are abundantly available in the markets during certain seasons. However, only a few people know that the grapes they buy might not necessarily come from Chaman.

Most of the grapes in the market are imported from Afghanistan, and their only connection to Chaman is that they come to Pakistan through the Chaman border.

Imran Kakar, the former president of the Chaman Chamber of Commerce, says that the production of grapes in Balochistan is ready in June and reaches the markets across the country within a month.

“When the local grape season ends, Kandahar grapes are ripe in Afghanistan by July 10. Most of these grapes come from the Afghan province of Kandahar and are transported to Pakistan via Chaman. These grapes are sold across the country as ‘Chaman’s Sundarkhani’ grapes.”

Imran Kakar explains that Chaman does not produce grapes on a large scale to send them to markets across the country.

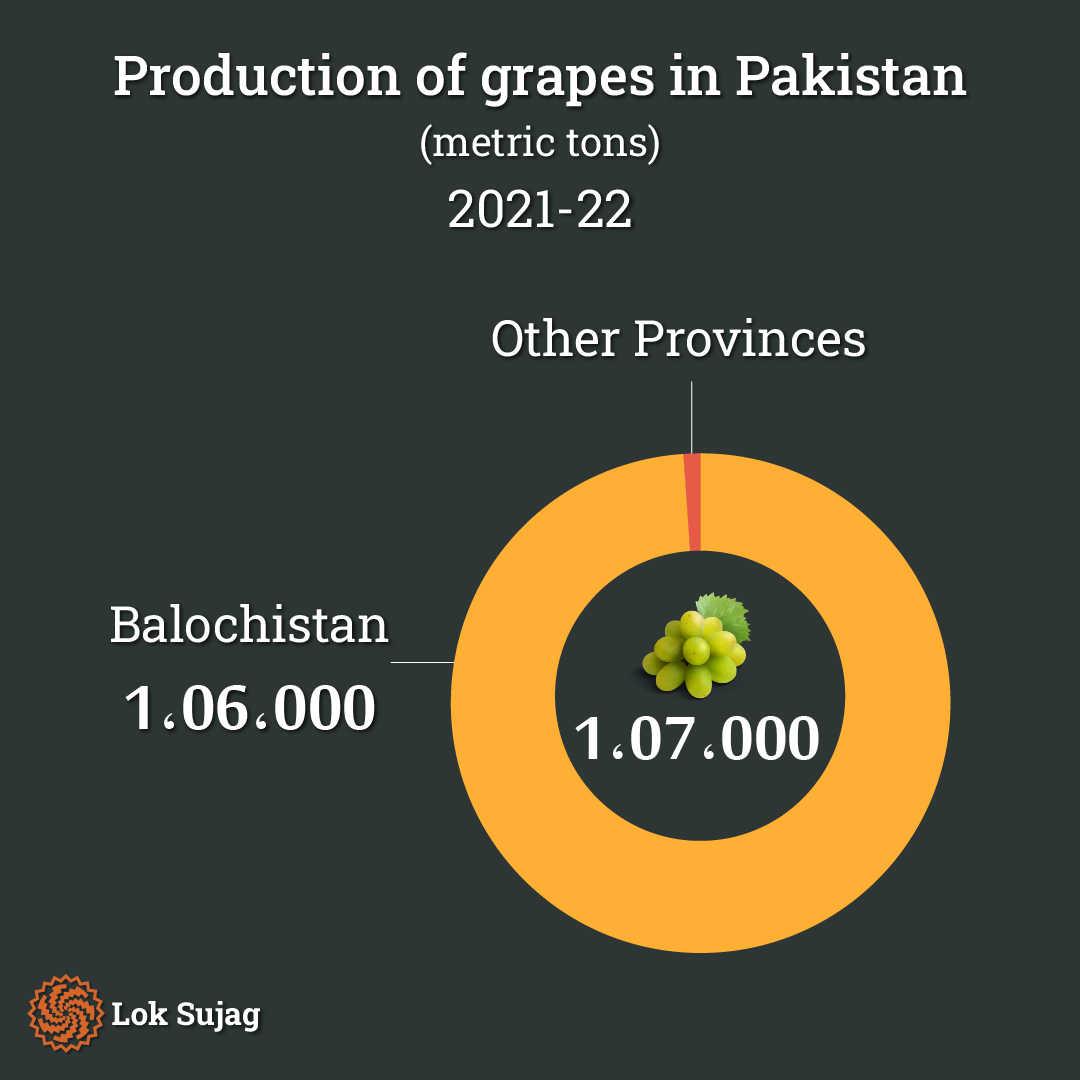

According to official statistics, grapes were cultivated on 39,500 acres across Pakistan in 2021. This year, the total domestic production was 170,000 metric tons, and 99 per cent of it, 160,000 metric tons, came from Balochistan.

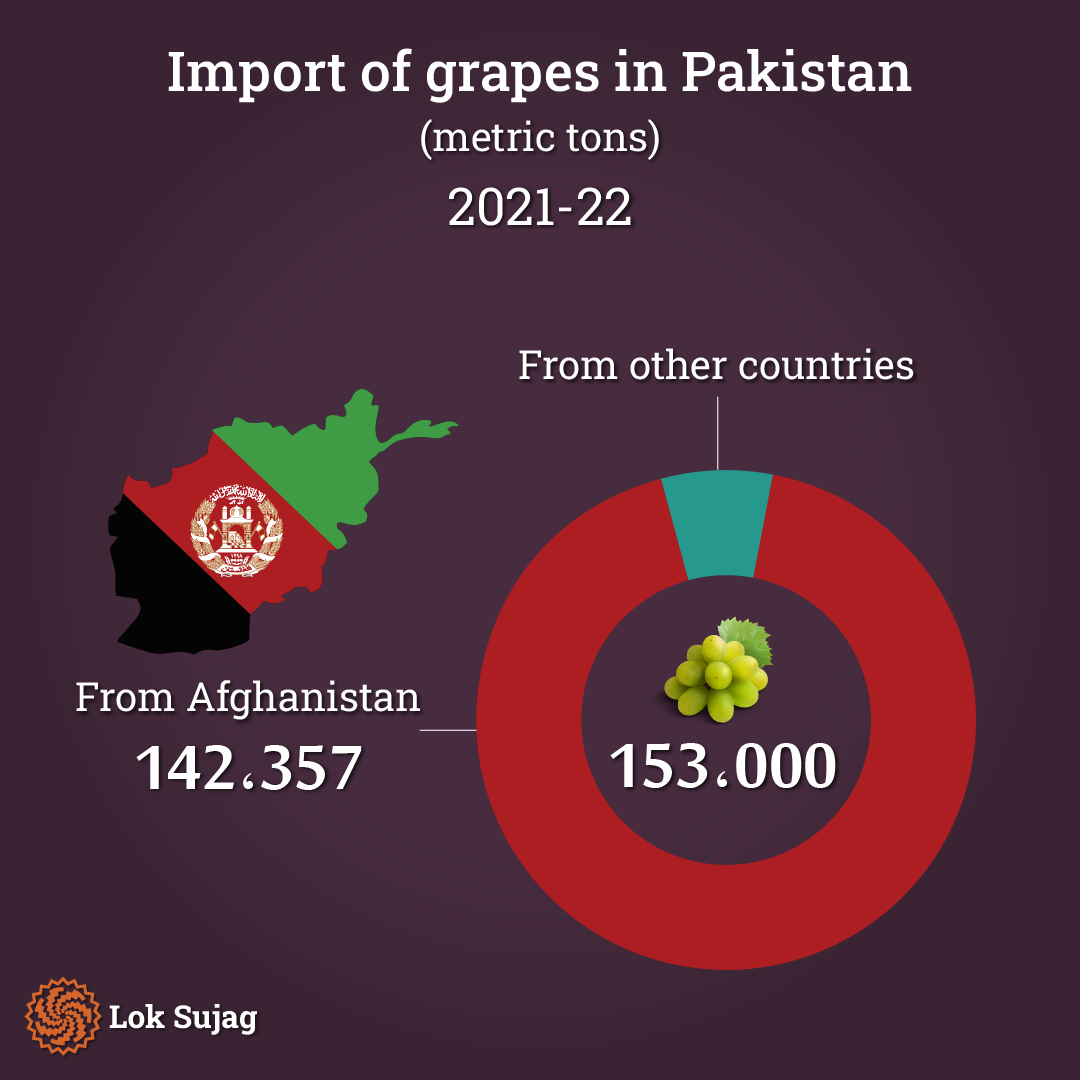

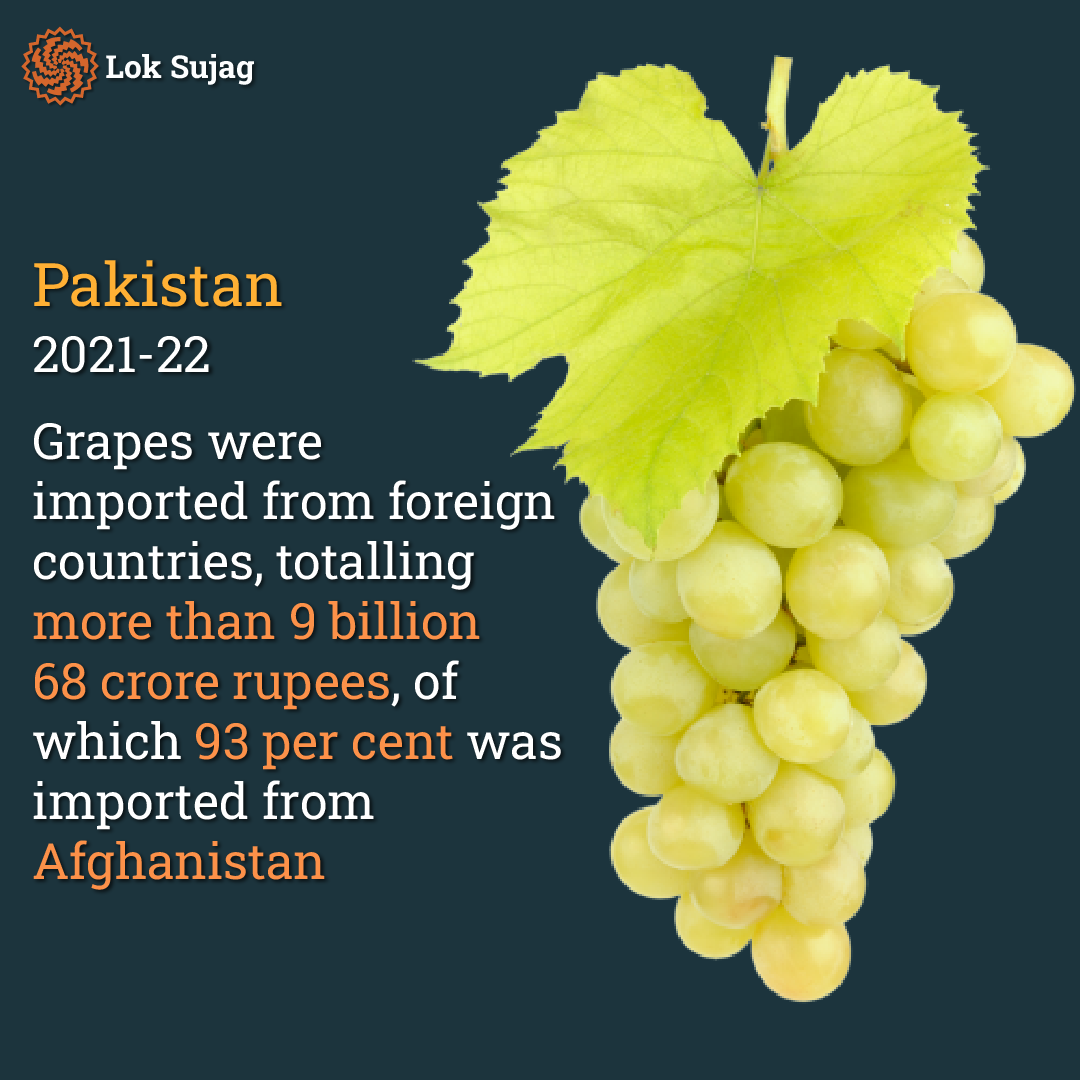

That year, 153,000 metric tons of grapes were imported from abroad, worth more than nine billion and 68 crore rupees. Out of this, one lakh 42,357 metric tons of grapes came from Afghanistan.

Chaman was separated from Qila Abdullah two years ago to form a separate district. In 2020-21, the area under grape cultivation in these two places was about five thousand acres.

According to Salim Yousafzai, director of agricultural research of Balochistan, the annual production of grapes in Chaman is 1600 metric tons.

Over 65 per cent of farmers in Chaman irrigate their grape orchards with Kariz. Kariz is an underground natural stream from the mountains and provides water for irrigation.

It has a safe flow of water from the spring to the winter season.

Aliullah, who hails from a village in Sui Kariz, grows grapes in his six-acre orchard. He says that due to drought in the last decade, the water has decreased in the Kariz, which has also affected the cultivation of grapes.

Apart from Kariz, farmers have now started relying on tube well water. But during summer, when grapes need water, load shedding also increases. Therefore, the conditions are not so favourable for optimum production of grapes.

Muhammad Zai usually grows Sundarkhani and Khimshi grapes in his two-acre garden in the middle of Chaman. This garden was cultivated by his elder brother two decades ago. In 2021, he earned one lakh 65 thousand rupees; in 2020, he earned one and a half lakh rupees from this garden.

He says that the grapes were damaged last year by rains and floods, and he could barely earn Rs 50,000 from the crop. This year, he has given his garden on contract for one lakh 85 thousand rupees.

Aliullah says that the entire province is affected by climate change. Last April, there was a lot of hail; in some places, stone-like hail fell, completely destroying the grape crop in certain areas.

“When it starts raining, it doesn’t stop. Too much rain damages the vines and causes diseases. Taking the grapes to the market becomes another problem. The roads are bad, and sometimes they get closed due to strikes or protests, causing the grapes to spoil in the vehicles.”

Balochistan grows six varieties of grapes, including Kalmak, Aita, Sundarkhani, Kishmshi, Toor, and Rocha. Grapes are cultivated more frequently in Chaman, Rocha, Sundarkhani, and Khimshi.

Rocha grapes are the first to be produced and reach the market by June 10, lasting about one month. After that, we get raisins, black grapes, kalmak, and sundarkhani. Finally, ita grapes arrive in the markets, which are ready about twenty days before autumn.

Mutiullah has cultivated four acres of grapes in the Kali Lindi Kariz area of Chaman, and he gets two hundred maunds of produce from it every year.

He says that the average cost of a new grapevine, from cultivation to production, is about 500 rupees. An acre has about 500 vines, so the cost per acre from cultivation to the first production of a new garden is around two to three hundred thousand rupees. The cost of irrigation alone is about 95 thousand rupees.

He says that the production of his garden is 50 maunds per acre. The production can increase if the agriculture department provides guidelines and the government offers cheap fertilisers and sprays.

Also Read

What is the threat to Mankira Melons?

Muhammad Zai, another farmer of Chaman, also says that the grape growers here have yet to receive any help from the agriculture department.

No cultivator ever came to inspect the crop in the orchards. The production of grapes in this area can be increased manifold, but the government will have to step up and provide support.

On the other hand, Sanaullah, the Deputy Director of the Agriculture Department, claims they provide all possible support to the grape growers to help them achieve a good harvest.

As proof of this, he also claims that grape cultivation in the Chaman district has increased by 40 per cent in the last five years. The area under grape cultivation is 180 acres, and the production has risen by about 400 metric tons.

He also mentions that occasional mites, aphids, and American cycads can affect the crop in June and July. However, this year, no disease has affected the grapes in Chaman.

Published on 27 Jul 2023