Sohrab Somro and his family reside in the ‘Jalo Jo Chuniro’ village in the Umerkot district. He works as a watchman at the local primary school. Three months ago, his 12-year-old son was crushed by a speeding long Jeep (Jaggado).

Injured Shah Nawaz was rushed to the hospital, but he succumbed to his injuries before reaching there.

The incident occurred on the Khokhra Par Chor Road in the Thar Desert. Sohrab Somro wanted to take legal action against the driver responsible for the death of his teenage son. However, due to pressure from the community, he had to pardon the guilty jeep driver, Ghulam Samejo.

Mohammad Fazal Somro, the uncle of the deceased Shah Nawaz, recounts that his innocent nephew’s body had just been placed in the courtyard of their home when the jeep driver, Ghulam Samejo, arrived with more than 50 respected members of his family. After the final rituals, all the respected visitors began seeking forgiveness.

“For centuries, the ‘Medh Manet Qaflay’ tradition has been prevalent in Sindh. The person responsible for an incident comes to the affected household, confesses the crime, and seeks forgiveness (known as ‘Tado Bakhshana’ in Sindhi), and he is pardoned.”

He says that as per tradition, Sohrab Somro also pardoned the driver. However, everyone unanimously agreed to restrict driver Ghulam Samejo from driving the off-road jeep on the Khokhra Par Chor route.

In Umerkot and Tharparkar, not just Shah Nawaz but several individuals, including the renowned ultrasound specialist Dr Niaz Samejo, have lost their lives in accidents involving these off-road long Jeeps. However, these incidents were not reported due to pardons, compensations, or the ‘Meerth Manet’ tradition.

For a long time, apart from camels, a particular type of truck (locally known as Kekra or Chakra) has been used between major towns and cities in the Thar region for transportation. These vehicles were indispensable for swift travel on sandy and uneven roads.

In the 1980s, jeeps became visible in certain areas along the Pakistan-India border. Most of these were models manufactured by Suzuki, called the ‘Samurai’ and ‘Shera,’ which were 5/7-seater four-wheel-drive vehicles. These cars were slightly longer than the typical jeeps; hence, they were also called long ones.

Due to their powerful engines (ranging from 1000 to 1500 cc) and off-road capabilities, these vehicles were used for smuggling along the border. However, fencing of the border by the late 1980s terminated this practice, leading these cars to be used for transporting passengers and goods instead. Since then, they’ve become the most popular mode of transportation in the desert.

Shafi Mohammad Bhambhro was involved in the car business for five years. He says that after 1986, the production of long jeeps had ceased. At that time, there were few Jeeps available, but as demand increased, the production of “cheap quality” long Jeeps began, and this business has been ongoing ever since.

“Local mechanics and denters buy old models such as the Half Hood, Pothohar, Shera, etc. They cut the back part and weld additional sections with the chassis (lower frame). Extending the frame about one and a half to two feet, they reshape the body into a ’long jeep.’ Locals refer to this as a ‘Juggaar.’

He says that alterations are made to the structure of these vehicles and the engines. This involves converting petrol engines into diesel. He claims that in Tharparkar and Umerkot, around 90 per cent of the jeeps (Juggari jeeps) running on roads are of cheap quality.

Mechanical engineer Nareesh Kumar Khatri explains that vehicles made through Juggaar lack safety standards.

“Adding length to the original chassis disrupts the vehicle’s balance.”

“He says that the jeep designed for five individuals has room for six, whereas the original long jeep can accommodate up to eight people. This means the company had allocated a capacity of around 300 to 400 kilograms of load.”

“The vehicles modified through Juggaar often bear five to six times more weight. Most of this weight sits on the extended part of the chassis, weakening the front tires’ grip on the road and compromising the vehicle’s control. Resultantly, accidents are more likely to occur during emergency brakes.”

Arshad Khaskheli is a workshop mechanic at Zero Point in Umerkot. He says that if a vehicle sells consistently, he can assemble one or two long jeeps within a month with the help of two labourers. He can save up to a hundred thousand rupees by managing the expenses.

“Converting a vehicle into a long jeep costs a minimum of five hundred thousand rupees. This includes fifty thousand for the front hood, fifty thousand for painting, two hundred thousand for the body, fifty thousand for wiring, and another two hundred thousand for converting petrol engines to diesel.”

Umerkot’s Bus Stand Manager, Jan Mohammad Mangrio, says that approximately 700 long jeeps arrive daily in Umerkot from Tharparkar and desert regions. These jeeps come from various routes, including Chhachhro, Koho via Ratnawar, Khokhra Par, Kunri via Chel Band, Khapro, and Achhro Thar routes.

He says there are around seven stands of these ‘Juggaari jeeps’ in Umerkot city. In various small and large towns in Tharparkar, numerous jeeps are parked, operating as local taxis.

Rano Mangrio has been driving his long jeep on the Umerkot-Dhebri route for 20 years. He says a newly built jeep costs at least 1.2 million rupees, and diesel is quite expensive.

“If I don’t take on 40 loads of goods and 25 to 30 passengers in the jeep, it doesn’t make ends meet. Sand dunes severely affect vehicles, and nothing can be saved from 3000 daily earnings.”

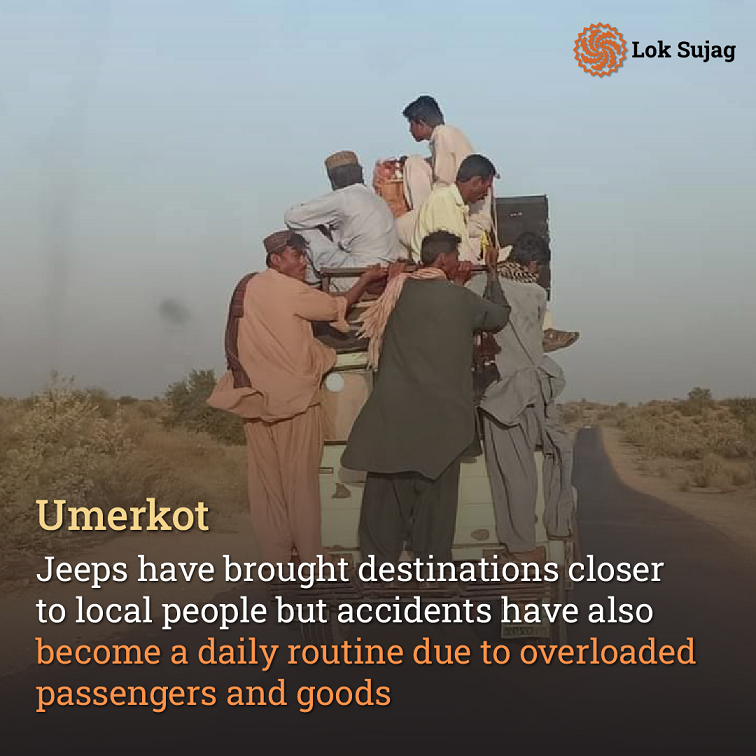

These jeeps have brought local destinations closer for people, but accidents have become a daily occurrence due to overloading with passengers and goods. However, neither the police have records of these accidents nor do the authorities have an estimate of the number of these Juggaaro jeeps on the roads.

Also Read

Multan Vehari Road: deterioration, accidents, and the long wait for repairs in seven key Punjab Constituencies

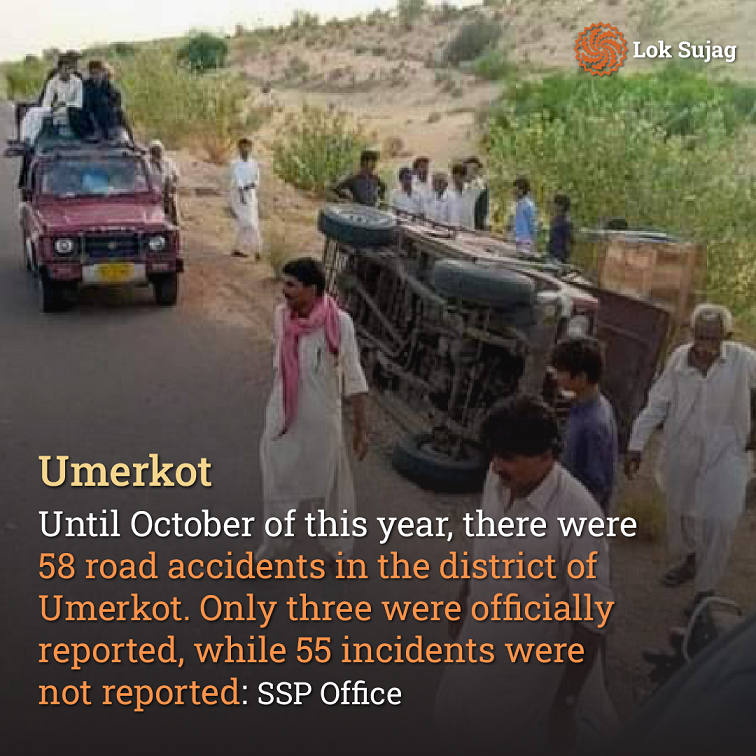

The SSP office in Umerkot lacks complete details of incidents in its data file. However, according to the available figures, until October of the current year, there have been 58 road accidents in the district, with only three being reported, while 55 couldn’t be documented.

“Abdul Sattar, the head of traffic police at Umerkot Traffic Police Station, acknowledges the negligence of the traffic police. He says that although numerous long jeeps arrive here daily, none of these vehicles have proper documentation. Most drivers lack licenses.”

“The entire system is running on political interference and recommendations. Whenever a sergeant intercepts a vehicle or driver, an assembly member or influential figure immediately calls to release their man. Forgiveness and settlements occur in case of an incident, even before an arrest. We are all helpless.”

Inspector Shah Mir Samoo confirms that most ‘cheap quality’ (illegally altered) cars are being driven in the area. He says that the alteration of these vehicles is not only illegal but also a crime. However, the registration of these cars takes place in Karachi; hence, they don’t have data for these jeeps.

Secretary RTA Umerkot Syed Shiraz Shah said, “Long jeeps do not fall under the category of commercial vehicles, so we cannot restrict their owners. However, last year, we issued tickets to 50 jeeps for not having licenses, route permits, and traffic rule violations.”

Fateh Ali Junijo has been driving in Thar for 23 years. He believes drivers, not the jeeps or vehicles, are responsible for accidents. He says that due to excess weight, long journeys, and rough roads, sometimes the axle, sometimes the chassis, or even the tie rods of the vehicle break.

“There is hardly any driver who has not met with an accident. If the traffic police and authorities desire, accidents can be reduced, but no one seems interested.”

Published on 29 Nov 2023