Some 15 years ago, followers of the banned sectarian outfit Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP) forced a Hindu sculptor Krishan in Tandu Ghulam Ali area of Sindh into abandoning his profession. Panicking in the face of threats from SSP, Krishan not only quit his profession but also left his home, relocating to the nearby Tharpharkar district.

Krishan was not alone in receiving such threats. Many of the Hindu sculptors of Hindu deities in the area still live with threats of violence. Raghu, a sculptor who taught the art of sculpting to others in the area, was threatened on several occasions to quit his profession. Raghu said he was told to stop sculpting or be prepared to meet a grisly end.

“I am 54 years old and it is not possible for me to learn something else for a living at this age,” he said.

Raghu said that without making sculptures he could not meet his family expenses. Besides, he asked, why should he quit sculpting something which did no harm to other religions.

A government official at the Tandu Ghulam Ali confirmed that many of the Hindu sculptors living there had approached authorities with complaints about the threats they were receiving.

The official who did not want to be named due to the religious sensitivity of the issue said that authorities usually calmed the sculptors saying no one would bother them in future. However, such threats and complaints continue to surface after a month or two.

He said that inaction on part of authorities was due to the fear that any action on the complaints could spark sectarian riots and destroy the area’s peace.

Syed Ejaz Shah, a local leader of the ruling Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), blamed the government policies of the past four decades that, he said, had fuelled intolerance and extremism in society.

The outfit - SSP - threatening the sculptors had been banned by the federal government, Shah said. "Despite the ban, its influence has increased over the past 15 to 20 years in our area."

However, he claimed, that most of the people in the town were tolerant to minority faiths. On their part, said Shah, the Hindu community and sculptors distribute rice dishes among mourners in the Muslim holy month of Muharram. "They feed the mourners in the Muharram processions that pass through their neighbourhoods and also set up sabeels [community stalls serving drinks to mourners] for them."

In addition to this, the sculptors also perform paint jobs in most of Muslim religious places.

The changing fortune of sculpting

Among the sculptors in Tandu Adam Ali is Wigha Ram, who sculpts his statues in the courtyard of the Rama Pir Ji temple. He lit a cheap cigarette while working on a sculpture of Shairanwali Mata along with his 19 years old assistant Mukesh and said the days they would receive orders from all over the country and all of them had jobs were long gone. “These days we wait for customers for days so we can pay for a square meal,” he said.

His father Bikha Ram helped build the Rama Pir Ji Mandir in 1971 but for many years, it remained without an idol as no one among the local Hindu community knew sculpting.

Wigha’s father sent Raghu to one of his relatives in Mirpur Khas, a city some 60 kilometres north of Tando Ghulam Ali, to master the art of sculpting.

On his return from Mirpur Khas, Wigha sculpted the first idol that was placed inside the temple.

Wigha said that this sparked a sculpting trend among the local Hindu youth. He said that a large number of children used to mill around the temple, hoping to learn sculpting.

“My younger brother would dash to the temple after school and stay here till late in the day, working on sculptures,” he said.

Resultantly, in the 1980s a large number of sculptors were working in the Tando Ghulam Ali and other villages on its outskirts. And all of them were making good money out of it.

Cheela Ram, a pupil of Raghu, said that in those days they would need to hire help to meet their orders. “I have made this house with income from sculpting, “ he points to a small, two-room house.

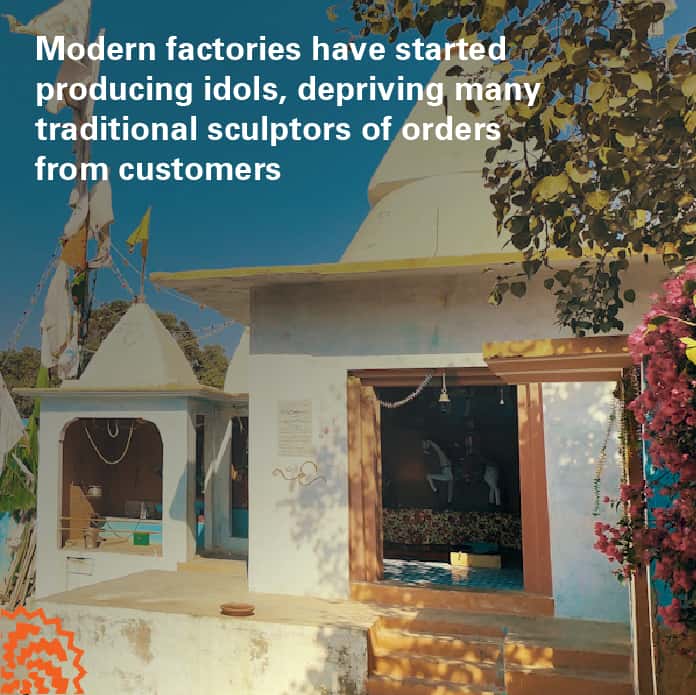

However, Wigha Ram said that over the past 15 years, modern factories of sculpting have opened up, dealing a death blow to the community sculpting culture, forcing many to take up something else to earn a livelihood.

Cheela Ram, 37, has now become a cobbler. "It is like someone has cast an evil eye on sculpting and it went up in smoke all of a sudden."

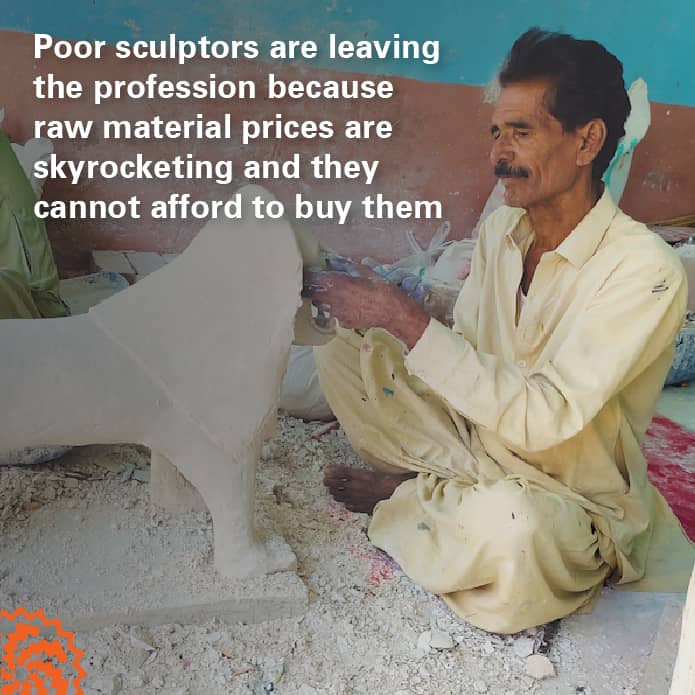

Another sculptor Nathu Mal said that the prices of items used in sculpting had skyrocketed and poor artisans could not afford to buy them, which was why the craft of sculpting was in decline.

Sawun Thakur, a sculptor living in Tandu Adam Ali, quit sculpting some 10 years back. "A sculpture costs Rs 10,000 to make but a customer is not ready to pay even Rs 7000 for it," he said.

Also Read

Karoonjhar range: Granite mining posing a threat to the ecologically diverse mountains of Nangarparkar

Thakur who now runs a rickshaw said that he had to take care of his children. He, therefore, quit the profession. “How is one supposed to carry on when the income from a thing is less than what you invest it,” he said.

Ban on holding melas due to Covid-19

Biman Das, caretaker of the Rama Pir Ji temple, said that before the pandemic, there used to be a three days festival arranged in Tando Ghulam Ali every year.

He said that people from all over Pakistan and India used to attend the event and local sculptors would earn good money from orders on the occasion.

However, he said the government had banned the event for the past two years to respond to the pandemic. "That closed down the few existing avenues for Hindu sculptors to earn."

PPP's Syed Ejaz Shah acknowledged banning the festival, promising the festival would resume soon once the pandemic situation improves.

However, he said, the decision to ban the event was taken in the public interest. “These restrictions have not only stopped Hindu festivals of the Tando Ghulam Ali but annual events of several Muslim dargahs [shrines of Muslim Sufi saints] have also been put on hold.”

Published on 7 Apr 2022