In 2011, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government decided to include five mother languages in the province’s educational curriculum, including Pashto, Hindko, Seraiki, Khowar and Kohistani. Four of these languages started being taught in schools by 2016 but the same could not be done with the Kohistani language.

Despite sincere efforts by the government, teaching of the Kohistani language faced a serious issue. When the Kohistani curriculum preparation began, a dispute arose between the Shina Kohistani and Indus Kohistani speakers.

Both insisted that their language was the original Kohistani language. As a result, a curriculum for this language could not be prepared.

What is the actual Kohistani language?

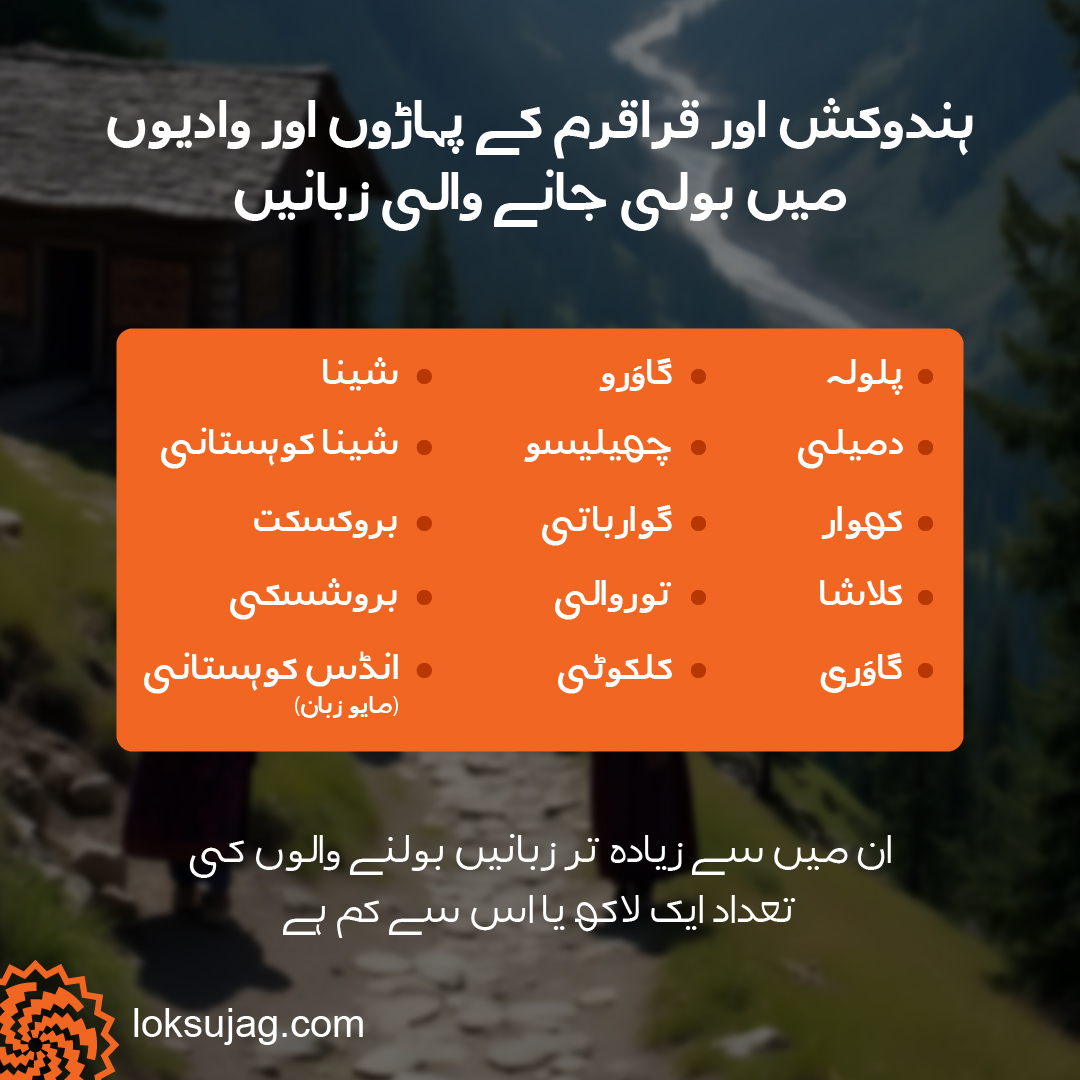

The various communities (tribes, groups or clans) living in the mountains and valleys of the Hindu Kush and Karakoram (including the Kohistan region) have been speaking their own separate languages for centuries. These languages include Shina, Shina Kohistani (Shina dialect), Indus Kohistani (Maiya language), Khowar, Gawri, Torwali, Kalasha, Palula, Dameli, Gawarbati, Kalkoti, Chilliso, Gowro, Brokskat, and Burushaski, among others.

According to experts, except for the language of Hunza, Burushaski, these languages belong to the same linguistic group, Dardic, which is itself a branch of the Indo-Aryan mega-group. However, each of these languages has its own distinct vocabulary, phonetics, grammar and sentence structure.

None of these communities or tribes can understand or speak the language of the others. Even the speakers of Shina Kohistani and Indus Kohistani rely on Urdu to communicate with each other. So why did the misunderstanding of considering these two separate languages as one language arise?

Kohistani – just a geographical reference

The word Kohistani means ‘mountainous people or their way of life’. It is neither a specific name of a language or community nor a culture or race. This geographical reference was given to the local inhabitants and everything associated with them by the foreign invaders and rulers who, by depriving them of their original identity, wanted to turn them into a subsidiary or additional unit. However, due to its continued usage, the term became common, and the new generations of local people began to incorporate the word Kohistani into their identity.

The Kohistan region is a vast area, which includes the regions of Hazara Kohistan, Indus Kohistan, Swat Kohistan (Kalam), and Dir Kohistan (Kumrat, etc.), where different languages are spoken.

Shina Kohistani, which is actually a dialect of the Shina language, is spoken in areas of Hazara Kohistan such as Battiara (Lower Kohistan), Palas, Kolai (district Kolai Palas), Dasu, Jalkot, Sazin, Harban, and Bhasha (Upper Kohistan). Meanwhile, the Maiya (Mayon) or Indus Kohistani language is spoken in Lower Kohistan in the areas like Pinkhad, Ranovali, Dubair, Jejal, and Pattan, and in the Upper Kohistan district in areas like Kamila, Seo, and the Kandia valley.

Online language databases like Ethnologue, Glottolog, and UNESCO also list Kohistani languages as Shina Kohistani and Indus Kohistani. However, the government and policymakers are not willing to discard the convenience of considering and referring to these different cultures as a single Kohistani.

Census worsens ambiguity

In the 2023 census, 14 languages of the country were included in the category of mother tongues, and Kohistani was included as a single language. With this ambiguous term, the mother tongue of about one million people in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa was recorded as Kohistani. Since no distinction was made between Shina Kohistani and Indus Kohistani, the confusion about them being the same language has become even more complicated.

According to unofficial statistics, more than 450,000 people speak Shina while approximately 300,000 speak Indus Kohistani. However, a large number of both linguistic groups still consider themselves Kohistani.

Since the term Kohistani is a geographical reference rather than an actual name, it is not just the Maiya and Shina speakers who call themselves Kohistani. In the Kumrat valley, some Gawri speakers and in Bahrain (Swat), some Torwali speakers also refer to their languages and themselves as Kohistani. These two groups, however, cannot understand each other’s languages and rely on Urdu or Pashto for communication.

However, in the 2023 census, more people from Bahrain did not consider their mother tongue to be Kohistani. In the entire tehsil, more than 141,000 individuals put their language under the ‘Other’ category, while about 30,000 wrote it as Kohistani, including Torwali, Gawri and Gojri.

Call to abandon ambiguous, non-indigenous terms

According to unofficial estimates, the number of people speaking the Torwali language in the Bahrain tehsil now exceeds 100,000, the Gawri community has about 60,000 speakers, and the Gojri community has a population of around 40,000.

However, it is being said that in the recent census, the mother tongue of some of these three communities was recorded as Pashto. According to the 2017 census, the Pashto population in this tehsil was about 60,000, which was reported to have increased to over 96,000 in 2023, while the total population of this tehsil only increased by 20,000 during this period.

Similar to Torwali, Gawri, and Gojri languages, the categories for languages like Gawarbati, Khowar, and Palalu in Chitral were also missing. Here too, some people were placed in the Kohistani category.

Whether Torwali or other Dardic-speaking linguistic groups of this region, all of them are closely related to the ancient Gandhara civilization of the Abasin and Swat regions. For them, the use of the term Kohistani is equivalent to marginalising them and cutting them off from their culture and history.

These languages represent the distinct culture, social traditions, and identity of the ancient inhabitants of this land. Instead of using ambiguous and non-indigenous terms for these languages, the names that are more local and well-known in academic and research circles should be used.

Published on 7 Mar 2025