A charpoy rests across the small water channel that irrigates paddy fields outside Chak 25-EB, tehsil Arifwala of district Pakpattan. It is early morning in August and Faryad’s family is having breakfast that includes vegetables and roti with a pitcher of milk water. The family had been at work since the morning prayer call when it was dark in a field flooded with almost knee-high water. They had toiled for two hours, planting paddy in the field. Barring Faryad, it is a predominantly female force that includes his wife, Razia, who seems to be calling the shots, and their two married daughters, Hina and Aisha, who, even after their marriages, have decided not to part ways with the well-oiled team.

Agriculture accounts for around 19pc of Pakistan’s GDP with about 38pc of the country’s total labour force employed in this sector. Furthermore, 55 to 60pc of the country’s agricultural labour is in Punjab and, according to various studies, women constitute around 40 to 50pc of this labour. In no other sector of Pakistan’s economy, the contribution of women is greater than in agriculture. Yet they continue to be treated as informal seasonal workers since the existing labour laws do not apply to the agriculture sector.

The search for more reliable sources of income that do not depend upon the changing of seasons or the vicissitudes of nature has led to the movement of male population to the urban areas of Punjab. In the cities, these men either learn technical skills or find office jobs with a regular pay. Some of them return to their villages to earn the extra buck when harvesting or sowing season starts.

With more number of men heading towards the cities, women fill the vacuum and make about half of the agriculture workforce. Without these women, Punjab’s agriculture industry would be struggling to cope with the growing pressure on the food supply chain.

The landless peasants of Punjab work as tenants, labourers or daily wagers at farms, a seasonal job. When the wheat crop turns golden or the maize kernel starts oozing milk or when monsoon comes and farmers plough fields for paddy, these farm workers know that their hour has come.

Since Faryad doesn’t own land and his family profession has been drum-beating which does not bring in enough money, he must wait for a crop cycle to either start or end to have some earnings.

The land owners sometimes engage contractors for a job to be done in a particular period against a lumpsum payment and the contractor hires daily wagers like Faryad. But most of the land around his village is held by small farmers, generally owning two to three acres, who deal directly with the workers like him without employing the intermediary contractor. “It’s much more convenient this way,” says Faryad while puffing at a cheap cigarette.

No respite from hearth to farm

It is the paddy sowing season. Hot and humid weather conditions make men and animals suffer alike, but it’s ideal for planting rice. Faryad has four days to sow one acre of land with the hybrid rice seedlings before he and his team would move on to the nearby plot of sesame seeds, which look ripe for harvesting.

“They divide up work equally. Weather permitting, they intend to fulfill the contract in four days, putting in eight hours a day, broken into two shifts of around four hours each, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. ‘This will hopefully get the job done,’ says Razia as the quartet gets up from the charpoy, gearing up to work after the meal break.

The women do as much work at the farms as their male counterparts. Whenever a field beckons, they respond in equal force, transplanting rice seedlings from the nurseries, planting the paddy in the fields, picking fruit and harvesting cotton, vegetables and wheat. But once they are home, away from the farms, they are on their own.

Razia’s duty roster is piled too high. Every day, there are chores that need to be done without fail and Faryad hardly ever lends a helping hand at home. She wakes up two hours before her husband, kneads wheat flour to make chapattis for her family at the firewood hearth in the open kitchen in their small courtyard. She wraps some roti in the tablecloth for her sons who go to school and will get up long after the family has left for the fields.

During summers, the family typically takes a late morning break from work, generally at about 10am as it gets too hot to work outside by that time. When they return to their little house on the outskirts of Chak 25-EB, she cannot relax like her husband who finds himself a bed. Her sons return from school and she prepares lunch for them. She has to feed the cows too. Fatima, the youngest daughter, who studies in Grade 8 in school, helps her mother in giving fodder to the cattle. She also milks the cows in the evening and her mother sweeps the cattle pen and cleans manger.

The cattle are kept under an arrangement called adhna, according to which the family takes care of the cattle on behalf of the owner and the milk as well as the offspring are split equally between both parties.

In the late afternoon, when the sun dips towards the west, the family troops towards the field for the last shift. They are rejoined by the two daughters, who had returned earlier to their homes to finish their chores. On their way, the party exchanges greetings with Tanzeela, a thin, middle-aged woman with deep wrinkles that belie her years, who is taking her water buffaloes to the village pond. Tanzeela has done her service to the family and farm for the day. It is time to tend to the beast.

A detailed study by the Food and Agriculture Organization on the state of farm workers concludes that in addition to their household chores, rural women also “manage the household livestock and poultry including feeding, cleaning sheds, fodder collection from the fields, milking and collecting produce such as milk and eggs”.

On the other side of the village, a cloud of chaff engulfs another couple, Rafique and his wife Sameena, who are vigorously threshing the sesame seeds out of the dried pods. This young couple belongs to a larger group of 16 cousins and relatives who work as a team. They hope to complete their contract within two days before they gird themselves to work in the rice fields.

Minimum wage—a foreign concept for workers

Effective from July 1, 2024, the Punjab government has set the minimum wage for workers at Rs37,000 per month. This means that no person, man or woman, should be paid less than this amount for a month’s work. Broken down in terms of daily wages, it comes to around Rs1,200.

The average contract rate is Rs10,000 per acre. In the case of Faryad’s family, it takes four persons to sow an acre of paddy field in four days, provided there are no rain interruptions—a common occurrence during the monsoon.

A simple calculation makes it Rs2,500 per head (Rs625 per day), which is about half of what they are entitled to receive by law.

“Even in the best of seasons, we earn somewhere between Rs25,000 to Rs30,000 per month,” says Razia who manages the accounts of her household as her husband is hopeless with figures.

The provincial government is not making any effort to implement the minimum wage law in the agriculture sector. All the farm workers interviewed in the Arifwala tehsil had no inkling of the minimum wage law. Moreover, nearly all the contracts are verbal. There is nothing on paper to refer to in case of a dispute or recourse to law.

Agriculture is not an industry that operates year-round with fixed pay. There are periods when there is no sowing or harvesting, just the wait for the crop to ripen. “There are four months when we find no fieldwork at all. These months are the hardest,” bemoans Razia.

So how do they survive?

“The shopkeepers are kind enough to lend us the groceries. They trust us to repay the loans when the farming season comes,” she replies.

That’s how it has been for as long as she can remember. They work tirelessly in the fields, earn enough to scrape by, repay the loans, remain idle during the dry periods and get more loans to be paid off during the farming season.

Then there are other loans. Faryad borrowed Rs250,000 for the marriage of their second daughter. Half of the loan has since been paid. He hopes to settle it by the time his third daughter comes of age. Going by the ages at which they marry off their girls, it should not be too far. ‘It’s so hard. Our earnings, even during the work season, barely provide subsistence. Then there are the heavy electricity bills that eat up our earnings,” laments Razia.

Work in sickness and in health

Antenatal or postnatal care does not qualify as sufficient ground for leaves for farm workers. Razia recalls that when she was pregnant with her first daughter, Hina. She could not take a break from work since it was the sowing season and the contracts had to be completed. Or the time when she was harvesting wheat with a sickle, carrying her second daughter, Aisha, in her womb while Hina toddled along with her. A few years later, when she and Hina planted seedlings in the field, Aisha rocked her baby brother to sleep on a hammock. Razia remembers breastfeeding all her six children in the shade during her breaks from work.

A report by the Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development on women agricultural workers in Sindh and Punjab states: “Women in rural areas are neglected and often do not receive proper nutritious diets, which results in poor health and leaves them prone to diseases. This, in turn, affects their productivity.” The study also mentions “alarm over pregnant women being forced to carry out challenging work on farms, which is detrimental to both women and their unborn children”.

“I never took time off, even during the pregnancy, even in the later stages when the child was due. There is no other way,” says Razia.

Faryad and Rafique acknowledge the sacrifices their wives make at the expense of their health, yet they will not move a muscle to help them out at home. “This is a woman’s responsibility,” says Faryad by way of explanation.

Farm work is backbreaking. Women who venture into the fields are exposed to great health risks. The constant bending posture required for planting, transplanting and weeding-related activities results in musculoskeletal disorders, such as back pain, joint pain and muscle strain. Insufficient diet during pregnancy and breastfeeding leads to weakness whereas exposure to extreme working conditions causes skin problems and respiratory ailments. Add to this the threat of insect and snake bites.

Razia complains of back pain, which is excruciating at times. Sameena experiences breathlessness and weakness. “It is as if there is no strength left in the body. All one wants to do is just lie down,” says Sameena.

Both women have sought medical help, both allopathic and herbal. Both have been prescribed rest. Both know that rest is not an option. “We also yearn for rest,” says Razia, looking ruefully at her husband.

With so many hands vying for a field job, a woman has only two options: she either works through all the discomfort and pain or risks losing her wages.

No schooling for girls

Sons are valued as families’ ticket out of poverty, that’s why they should be educated. If a boy manages to pass the Matric exams, he can get a job in a government department or the military that would ensure a steady income for the family.

On the contrary, an educated girl would be of no long-term benefit. Nearly all men of Chak 25-EB have this mindset. They hold that the fruits of a girl’s education will be reaped by her future household. But before that she can be of greater utility by working in the fields and adding to the family income.

Razia dropped out of school after the fifth grade. Her two daughters were forced to quit their studies after primary school as the family needed them on the farms. Her sons, though, go to school in the morning and loiter in the evenings.

Sameena never saw school but wants her sons to make it to college. “We have done the hard work. We don’t want our offspring to toil on the farms,” she says.

This way of thinking has led to a high dropout rate among the village girls. Moreover, there is little understanding that girls, too, can vie for the jobs they want their sons to get, provided they are not forced to quit school.

Fathers, due to patriarchal thoughts, want them to be trained in the ways of their mothers, not only on the farms but also at home, helping mothers with the chores and taking care of the younger siblings.

In a typical Punjab village, there is a common sight of a little girl carrying her younger sibling or running after the cattle. The boys, on the other hand, are spotted playing cricket or chasing each other. This makes one wonder who would make a better leader if exposed to higher education: one who has been saddled with responsibilities from the time she learned to walk or the urchin chasing after a stray dog.

Need for legal protection

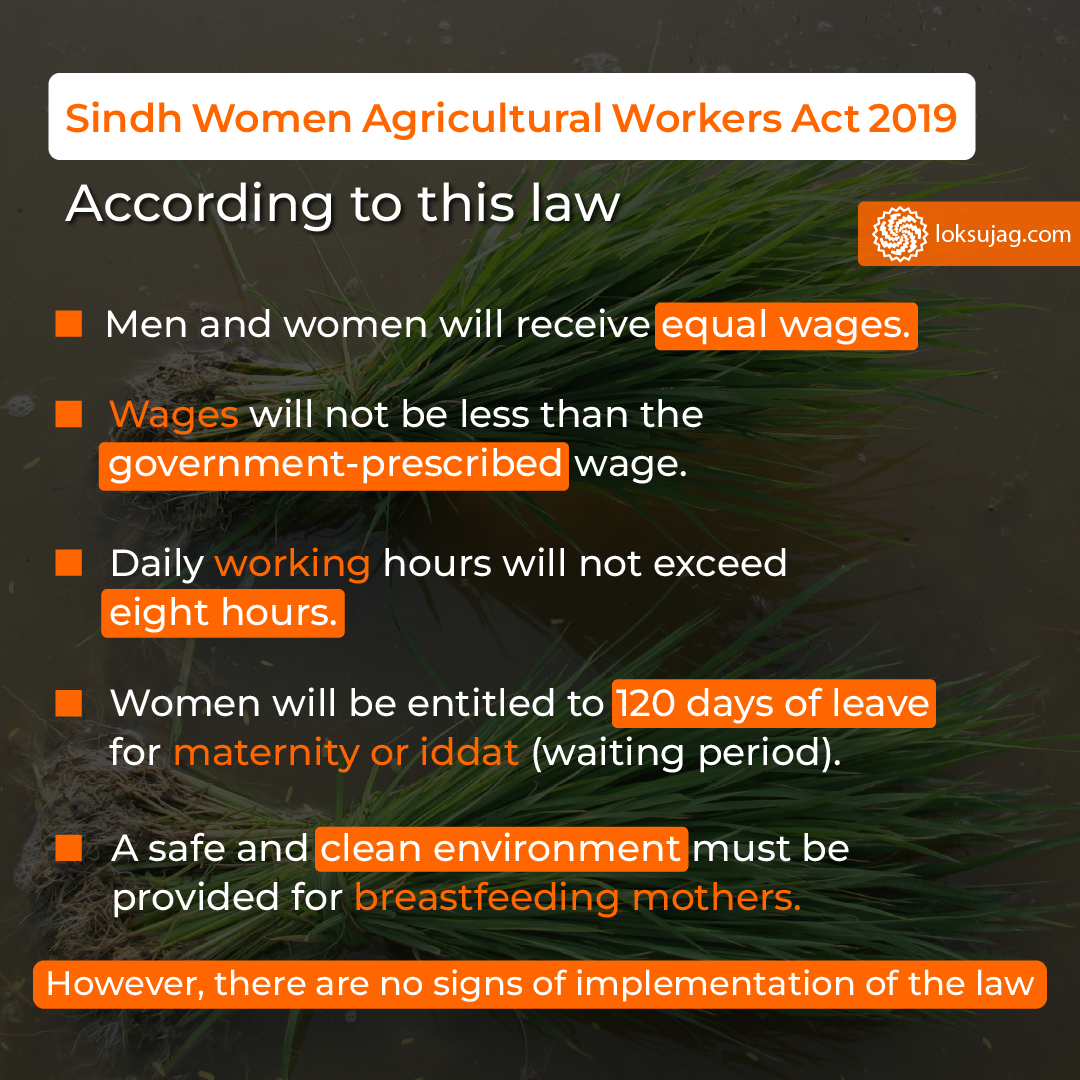

The Sindh government took the lead in recognizing the need to regulate the rights of women farm workers by enacting the Sindh Women Agricultural Workers Act, 2019. Among other provisions, the act decreed equal pay for

women in relation to male workers, which cannot drop below the minimum wage fixed by the government. Moreover, work done in the agricultural sector must be backed by ‘a written contract of employment’.

The law also fixed minimum working hours at eight hours per day and entitled women to 120 days of maternity leave along with Iddat leave. It also dictated that nursing mothers must have access to ‘safe and hygienic conditions’ where they can breastfeed their children.

Also read this

Struggles of women labourers in Hyderabad’s vegetable market: Seeking recognition and fair wages

Five years after the enactment of the law, the Sindh government has little to show in terms of implementation, according to the Hari Welfare Association. Yet, at least it recognises women as a legitimate labour force, with exclusive rights to be protected and enforced.

The Punjab Home-Based Workers Act 2023 is a step towards protecting the rights of informal workers in Punjab, including those working in the agricultural sector. This act makes it binding on the employer to sign a written contract with the home-based worker they seek to engage. It also provides for health benefits and safeguards against discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, creed, gender, etc. Punjab also needs a women agricultural workers law, similar to the one enforced in Sindh, one that will cater to the specific needs of female farm laborers. But no law is good enough unless it is implemented. Otherwise, it is just a gazette notification.

The sun has set, and Razia’s back is killing her. They have managed to complete the task under the contract and it is time for some reprieve. She sends her husband to the grocery shop on the street corner. The shop also stocks some medicine that she needs to alleviate her pain. She takes some money out of their wages and clenches it in her fist. Maybe, after paying for the medicine and Faryad’s cigarettes, there will be some money left for her favourite juice.

This essay was commissioned by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan.

Published on 23 Apr 2025