Munir Hussain is a resident of Bhamman Jhagian, a suburb of Lahore. His house is 20 km away from the city. In his village, he owns a fruit cart on which his family’s livelihood depends.

He says that his third child was about to be born four months ago. When his wife suddenly started experiencing pain at night, he immediately took her to a local midwife who is employed at a private hospital and has set up a clinic at home.

“At the midwife’s home, my wife went into labour, but moments after the birth of the newborn girl, she passed away. I am deeply saddened, but thanks to God, my wife’s life was saved.”

Munir Hussain said that the Basic Health Unit (BHU) is seven kilometres from his home but closes in the afternoon.

However, he had taken his wife there once for an ultrasound. The second time when he took his wife to the hospital, the medical staff ignored them by giving a receipt without conducting a check-up. Therefore, no complication in the pregnancy was recorded.

Resident Bushra Bibi from the nearby village of Attoke Awan explains that whenever she visits the local Basic Health Unit (BHU) to get medicines, she has to wait for hours. Then, the dispenser gives everyone the same pills and syrup. If a pregnant woman comes, she is given a prescription for medicines to be bought from the market, costing around two and a half thousand rupees.

Kiran Bibi, present along with Bushra Bibi, shares that her delivery took place at the same Basic Health Unit a few months ago. She complains about the female hospital staff’s behaviour being extremely humiliating. Now, she only comes here for medication for common ailments such as cold and fever.

Not only Bushra Bibi, Kiran, or Munir Hussain, but also most people living in rural areas face difficulties seeking medical treatment. As a result, reliance on quackery is on the rise.

According to recent census data, out of Punjab’s population of over 12 crore and 76 lakhs, 59.30 per cent of people reside in rural areas. Based on this, out of Lahore Division’s approximate population of 227 million, around 139 million people live in rural areas.

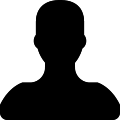

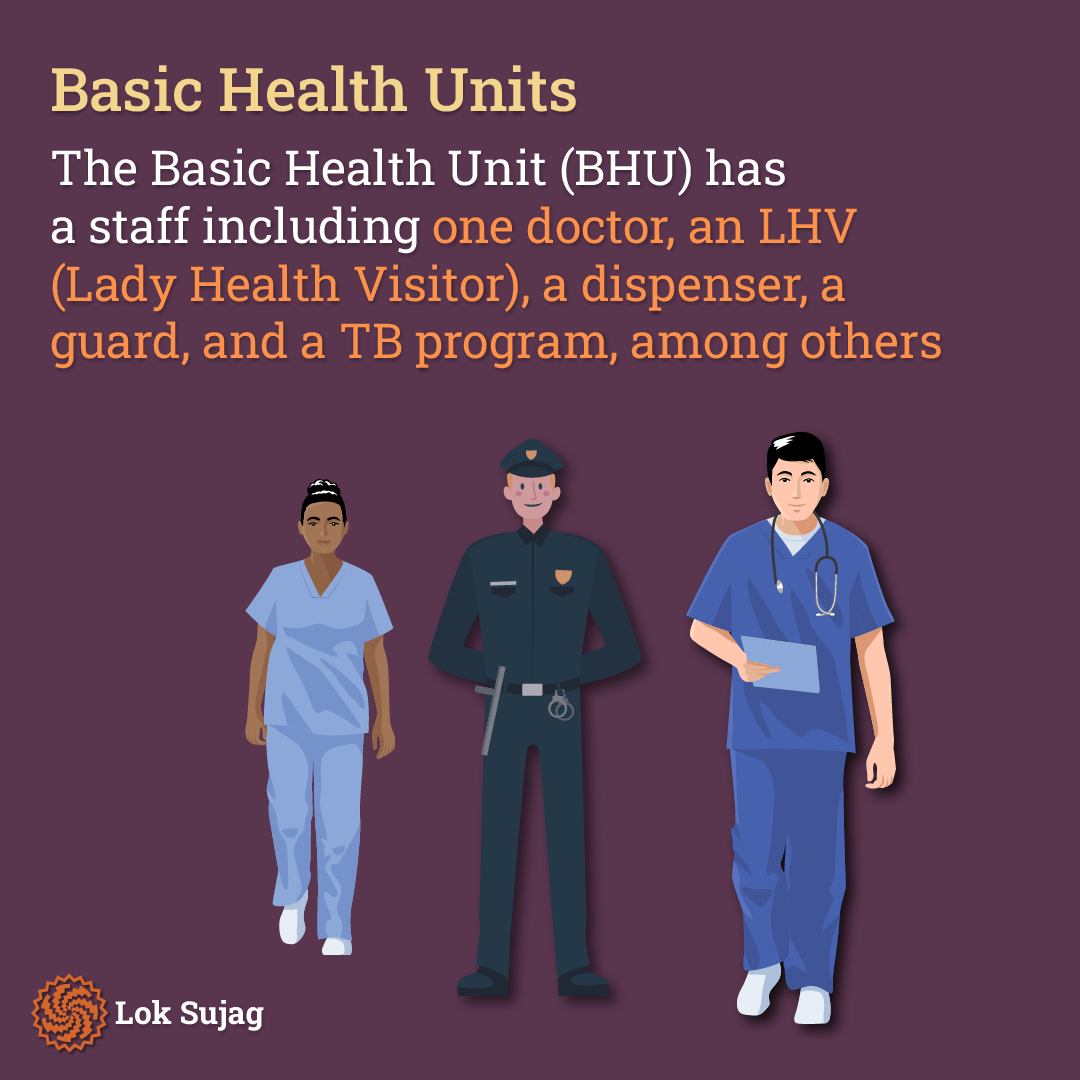

The Health Department (Specialized Health Care and Medical Education) of Punjab’s website states that there are 293 Rural Health Centers and 2,461 Basic Health Units in towns and villages across the province. The Lahore Division has 34 Rural Health Centers (RHC) and 246 Basic Health Units (BHU) operational.

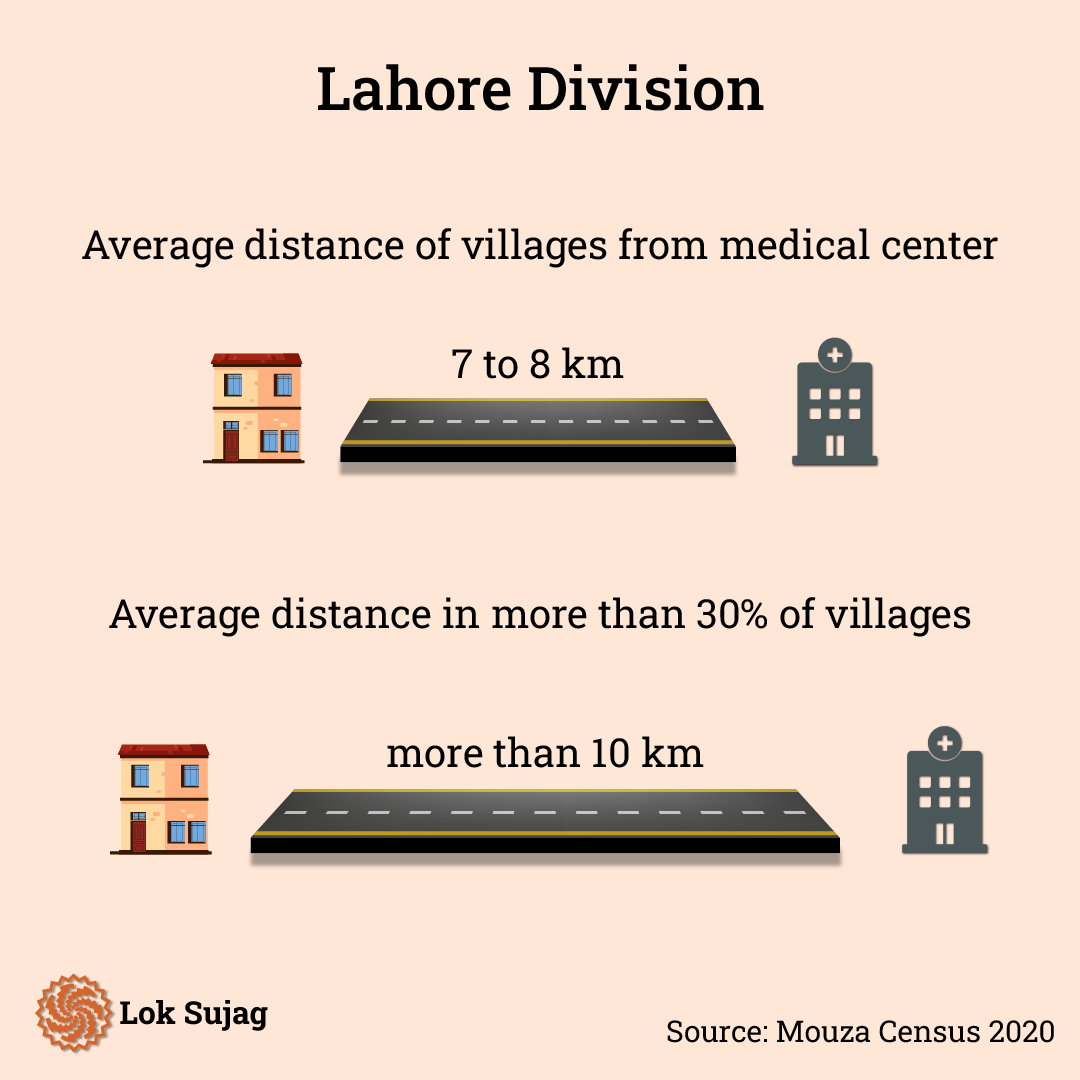

Mouza Census 2020 data indicates that of approximately 1,566 villages in the Lahore Division, around 34 per cent have either a Basic Health Unit (BHU) or a Rural Health Center (RHC). The average distance from villages to medical centres in the division is seven to eight kilometres, while over 30 per cent of the villages are more than 10 kilometres away.

According to the census, in the villages of Lahore Division, no doctor’s private clinic or even a trained midwife is available at a distance of less than ten kilometres. Despite this, the government health centres here are closed only in the afternoon.

For the past fifteen years, Dr Shakeel Ahmed has served at the Basic Health Unit in Dograi Kallan, near Wahga Town. Approximately 70 to 80 individuals visit here for treatment daily. Dograi Kallan is located 16 kilometres from Lahore city, and the population of Union Council exceeds 50,000.

Dr Shakeel confirms that there are insufficient staff and facilities at the Basic Health Unit (BHU). He mentions that the government has made online registration mandatory for patients. Entering details about the patient, illness, and medication on a mobile/tablet consumes considerable time. As a result, the number of patients coming here has also decreased.

He says that the Out-Door Patient (OPD) facility at the Basic Health Unit (BHU) is available until two in the afternoon, while the maternity services are accessible 24 hours a day. An LHV (Lady Health Visitor), midwife, and security guard are on duty even at night. Basic diagnostic tests are available here, but they are charged a separate fee.

“At the BHU, the staff includes one doctor, an LHV, a midwife, a dispenser, a security guard, and a TB program staff member, etc. On the other hand, the situation of doctors and staff at the Rural Health Centers (RHCs) is relatively better. There, facilities like a 20-bed ward are available for patients.”

Dr Shakeel Ahmed says that BHUs and RHCs were established in the 1970s under the Primary Health Program. At that time, one BHU was built for a population of five to ten thousand. The population has increased significantly, but the staff numbers have not been increased accordingly.

He mentioned that in the rural areas of Lahore District, along with BHU, six RHCs are working. Apart from this, there are two government hospitals in both Kahana and Manawan, run by an NGO called Indus. However, these additional facilities are not available in every village.

Residences were also constructed for doctors in every BHU and RHC. However, most of them have now turned into ruins. Their windows and doors are missing. In any case, doctors were not inclined to stay there.

According to Dr Shakeel, the buildings of Basic Health Units (BHUs) and Rural Health Centers (RHCs) have now completed their lifespan.

Rana Ijaz Ahmed, the former chairman of the Union Council of Wahga Town, says that public transport is not readily available from Wahga Town to Awan Dhaiwala for RHC services. As a result, some people take patients to the government hospital in Manawa.

He says that most people here cannot afford the expenses of private hospitals. Therefore, they resort to charlatans.

In the villages, no MBBS doctor sets up a clinic. Doctors are available in nearby towns such as Jalomorh, Batapur, Manawa, Barki, etc., but none charge less than two hundred rupees. They also close their clinics in the evening and leave.

Rana Ijaz mentions that emergencies become more critical at night. At such times, charlatans provide services. They provide medicines for fifty rupees and, if necessary, administer injections at home.

Alina Azhar, a representative of the non-governmental organisation ASRA, working for women and children, shares that the condition is worse in rural areas of other villages as compared to Lahore division. BHUs are the best model for basic health in rural regions, but unfortunately, these centres have not been upgraded according to the population’s growing needs.

According to her, if rural health centres can have at least two shifts of doctors, it would significantly improve the situation. Similarly, providing free medicines and diagnostic facilities here would reduce people’s problems and diminish reliance on quackers.

Also Read

Critical healthcare crisis in Tando Mohammad Khan District Hospital reveals severe shortcomings and depleted facilities

Regarding the Basic and Rural Health Centers, the concerned Provincial Minister and Secretary of Primary Health have not responded to any queries. However, the spokesperson of the Health Department, Sohail Janjua, says that 24-hour maternity services have been made available in the province’s 855 Basic Health Centers.

He says a thousand doctors have been hired for maternity services, and 400 lady doctors are being recruited. BHUs and RHCs report regularly every month, and the staff’s attendance is checked through the online system.

These initiatives are improving the condition of health centres.

According to the latest report from the World Bank, Pakistan spent $38.18 per capita on health in 2020, while the World Health Organisation recommends a minimum of $44 per capita.

The Economic Survey of Pakistan for the year 2022-23 indicates that the health budget for the fiscal year 2023 in Punjab was reduced by 50 per cent compared to the previous year. Similarly, the budget for Specialised Health Care and Medical Education was cut by three per cent.

Published on 30 Nov 2023