Nine-year-old Ishraq Ahmed, lovingly called Bobby, went out to play as soon as he came home from school.

His mother Salma Bibi got worried when he did not return even after the sunset, forcing her to go out into the streets to look for him. Her husband Munawar Husain is suffering from paralysis and was unable to carry out the search for their son. So, despite feeling weak on account of having given birth to a baby girl a few days earlier, Bibi continued her quest for Bobby until late in the night. All to no avail.

The next day, she lodged a First Information Report (FIR) with a nearby police station about his disappearance. A day later, the police found his body in a sugarcane field not far from his home. He was strangulated with his own shirt. His autopsy report later confirmed that he was killed after he was raped.

This incident took place between January 9th and January 11th in 2018 in Dholan village (Chak No 27) in Pattoki tehsil of Kasur district. It, thus, coincided with the rape and murder of a seven-year-old girl, Zainab Ansari, in the same district. Her case was making headlines daily then, resulting in huge pressure on the district police to take effective measures for putting an end to the burgeoning incidents of sexual crimes against children.

Consequently, the police arrested a number of suspects from Dholan village and tortured them at Saddar police station in Pattoki to extract confessions. This arrest and torture operation gave the residents of the village an impression that it was being done at the behest of Bibi. Many people who had earlier joined her search for her son, thereafter distanced themselves from her.

During the controversial investigation process, however, the police also collected deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) samples from several locals which were matched with the DNA found at Bobby’s body. The analysis of these samples finally established that his neighbour, Farhan Ahmed, 20, had committed the crime.

Ahmad was arrested on May 5th, 2019. He revealed during interrogation that he, along with his neighbour Salman Rafique, took Bobby to a sugarcane field where they raped him before strangling him to death.

Following his arrest, Ahmad was tried in the court of Kasur’s additional district and sessions judge and was sentenced to death towards the end of 2019. He is currently imprisoned in a Lahore jail while his appeal against his death sentence is pending before the Lahore High Court.

Bibi, on the other hand, is still awaiting the arrest of his co-accused.

During initial investigation in the case in May 2019, a police official told the investigating officer that all his efforts to apprehend Rafique had borne no fruit. Bibi believes that he had flown to Saudi Arabia after having his name changed to Irfan Rafique in his national identity card and passport.

This is the main reason why he is still at large. Whenever the police approached his family for his arrest, they would say they did not know anyone with the name of Salman Rafique, says Bibi.

Due to his constant absence from the proceedings of the case, the court has declared him a proclaimed offender. Bibi claims to have informed the police about his presence at his home when he recently returned from abroad. But, she says, the police was too disinterested to take any action to arrest him.

Also, she alleges, to prevent her from pursuing the case, Rafiq’s family lodged a fabricated case of armed robbery against her paralyzed husband. The police dismissed the case on their own after seeing his condition.

After this incident, Rafiq’s family shifted to some unknown place. Had the police acted in time, says Bibi, they would not have succeeded in fleeing from the village.

In 2020, she, too, had to sell her house to defray the expenses of the case. She then shifted to a rented house in Khuddian Khas area of Kasur district, about 50 kilometres east of Dholan. But she regularly calls the investigating officer at Saddar police station in Pattoki for updates on Rafiq’s arrest. At times, when she does not get a proper response, she also visits the police station herself.

These visits, however, are becoming increasingly difficult for her because, after shifting to a new locality, she has to cover a long distance to reach the police station. In addition, she has to take care of her paralyzed husband and three young children whom she cannot always leave back at home.

She is also facing financial constraints because her only source of income is the salary of her son, Zain, who works as a gardener at a government school on a monthly salary of 16,000 rupees.

Money matters

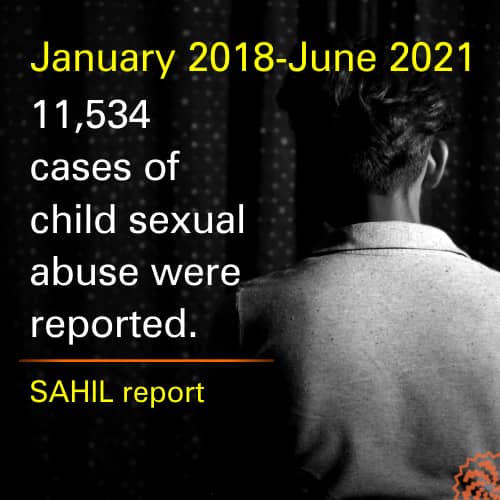

According to a report compiled by SAHIL, a non-government organization working on child rights, hundreds of children are sexually abused in Pakistan every year. In the first half of 2021 alone, 1,896 such incidents have been reported.

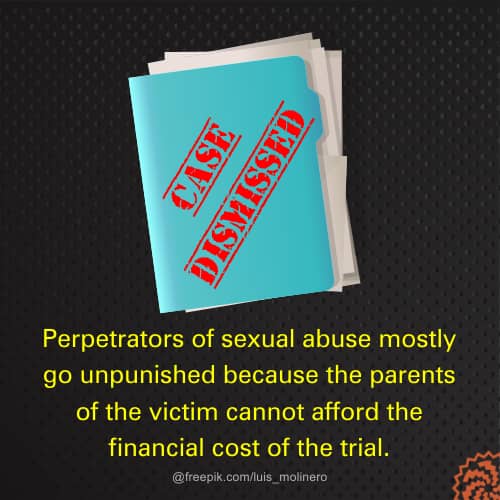

SAHIL’s provincial coordinator Ansar Sajjad Bhatti says most of the accused in these incidents go unpunished because, just like Bibi, the parents of most of the victims do not have adequate financial resources to pursue cases.

He knows about a number of incidents in which “despite the presence of solid evidence, the perpetrators of sexual abuse could not be convicted mainly because of the inability of the victims’ parents to bear the financial burden of litigation.”

One such incident took place at the Audit and Accounts Housing Society in south Lahore last year.

Its 16-year-old resident Waleed was going somewhere one day when his motorcycle ran out of petrol. A stranger -- later identified as Shahbaz, aged around 27 years -- came to his rescue. After he arranged fuel for Waleed’s motorcycle, the two exchanged phone numbers and became friends.

But, on March 3rd, 2020, Shahbaz and one of his friends abducted Waleed and gang-raped him at gunpoint. When their victim’s father Riaz Akbar came to know about the incident, he lodged a First Information Report with the area police. Resultantly, Shahbaz was put behind bars.

Akbar claims the accused comes from an influential family so he ensured, through bribes, that his DNA analysis report never became known. In the meanwhile, he also started threatening Akbar of dire consequences if he continued to pursue the case.

These pressure tactics notwithstanding, Akbar was determined to follow the case but, as he says, he did not earn enough money from his job as an audit officer to cover legal and judicial expenses. He, therefore, lost interest in litigation and, as a result, the court released Shahbaz on bail in August 2020.

Dearth of sufficient financial resources for litigation also forced Ghulam Sarwar to pardon a man who had tried to rape his 10-year-old son Hasnain in Khayaban-i-Amin, a residential area in south Lahore.

Sarwar works as a security guard in the same locality for a meagre monthly salary of 16,000 rupees. Hasnain used to bring lunch for him every afternoon from their home in Halloki village, located three kilometres from Khayaban-i-Amin.

On June 8th, 2020, Hasnain was taking the meal to his father when Aftab Hasan, a vegetable seller in Khyaban-i-Amin, abducted him and tried to rape him. Hasnain’s loud screams to resist the assault, however, drew the attention of a passer-by who not only rescued him but also handed over the perpetrator to the police.

A few days later, Hassan’s mother, aunt and grandmother went to Sarwar’s house and put their shawls on his feet — a centuries-old tradition of Punjab to get pardon from the offended party — and asked him to forgive him. Sarwar accepted their request which subsequently led to Hassan’s release on bail.

But two months after his release, Hasnain went missing. His mother Farzana Bibi suspects that Hassan has abducted her son but Sarwar does not agree with her. They, therefore, have not yet taken any legal action against him.

Going scot-free

Atif Khan, a Lahore-based lawyer who works with SAHIL, has appeared as counsel for a number of children subjected to sexual abuse. This crime, he says, is punishable by death under a law promulgated in 2006 yet there has been no significant reduction in its incidence.

According to a report compiled by SAHIL, a total of 3,832 cases of child sexual abuse were reported in national newspapers in 2018. Their number declined to 2,846 in 2019 but it rose again in 2020 to 2,960. In other words, an average of nine children were sexually abused every day over the last three years.

Legal experts are of the opinion that most of the people involved in such cases were never convicted because of various lacunas in the judicial process. “In most cases, families of the victims pardon the perpetrators because they either do not have adequate financial resources to pursue cases or they do so due to social pressures and to avoid reprisals,” says Khan.

Under Pakistan’s laws, rape is not a compoundable offence. In theory, this bars the families of rape victims to enter into any compromise with the perpetrators. But, after having an out-of-court settlement, they intentionally change their statements in courts so as to change the nature of the crime, he says. “Making such changes in statements before a court is itself a crime but the police never takes action against them for doing this.”

The spokesman of Punjab Prosecutor General’s Office, Nadeem Iqbal Khakwani, contends that courts are equally responsible for this state of affairs. “Instead of relying on forensic evidence, they usually decide cases on the basis of verbal testimonies,” he says and regrets the fact that even such solid evidence as medical reports and DNA analysis stand irrelevant if a plaintiff resorts to changing his verbal statement.

Published on 18 Oct 2021