Sardar Khan migrated to Lahore some 30 years ago to improve his life and livelihood. He and his family, however, are yet to be officially recognized as local citizens.

His ancestral home is in Bada village of Topi tehsil in Swabi district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Presently, he lives with his five sons and other family members in a small rented house in Al-Falah Town in eastern part of Lahore.

All five of his sons work in private sector in different parts of the city. One of them, 26-year-old Murad Khan, works as a driver in Defence area and is also studying as a private student. “Even though I have spent all my life in Lahore, I still cannot vote in this city,” he says.

His vote, indeed, is not registered here. The government officials told him that this is because the name of his ancestral village is still listed on his national identity card (NIC) as his permanent address.

Khalil Khan has the same complaint. He has been running a clothing business in Lahore for the last 10 years. Both his shop and residence are located in Bhatta Chowk area in eastern Lahore though Zaray, his hometown, is located in Mamond tehsil of Bajaur tribal district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Khalil Khan, 30, says a military operation was launched in 2008 against religious militant groups based in his area. This led to the displacement of thousands of local residents. He was also uprooted owing to the military swoop and was forced to take refuge in Lahore. After some time, he set up his business in the city and later also brought his family here.

Khalil Khan says the census officials did visit his house in 2017. But, after seeing his NIC, they refused to count him and his family in Lahore’s population because the name of his village was listed as his permanent address on his identity card.

What makes Pakhtuns resent 2017Census?

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics — the federal agency responsible for compiling national statistics — has recently released the final results of the 2017 census. These put the total population of Lahore at 11.12 million. Compared to the 1998 census, the city’s population has increased by 4.8 million people in 19 years.

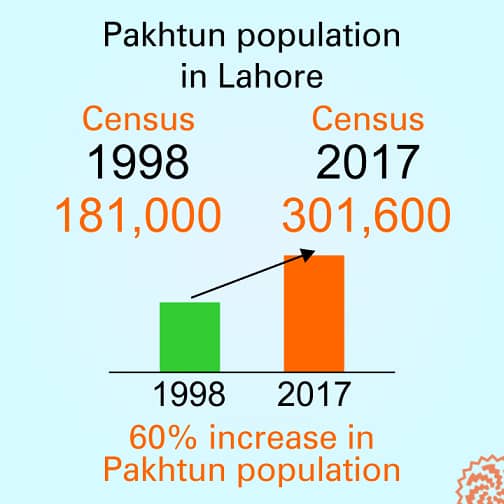

According to the latest census data, a large portion of this population (80.94 per cent) consists of Punjabi speakers while 12.62 per cent of it speaks Urdu. Pashto is the third largest language spoken in the city, with more than 300,000 speakers. This number has increased by 181,055 as compared to 1998.

It means that Lahore’s Pakhtun population has increased by 60 per cent between the last two censuses. The city’s total population, on the other hand, has increased by 43 per cent in the same period.

But, despite the fact that Lahore’s Pakhtun population has grown faster than its total population, Murad Khan, Khalil Khan and members of various Pakhtun nationalist parties in the city are not happy with the 2017 census. They claim that a large number of local Pakhtuns are either not counted in it or are deliberately portrayed as residents of other places.

Ameer Bahadur Khan, provincial general secretary of Awami National Party, the largest Pakhtun nationalist party in Pakistan, claims that at least 1.5 million Pakhtuns live in Lahore but most of them are not recognized as locals. The permanent address given on their identity cards is the basic reason why this is so, he says.

Gul Muhammad Regwal, a member of the Lahore chapter of Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party, also claims that the total number of Pashtuns living in Lahore is more than one million. He insists that 300,000 Pashtuns live and work in the walled city area alone and alleges that they were not properly counted in the 2017 census as part of a “plan” to keep their representation in local politics to a minimum.

Many of those who have been living in Lahore for the last 10 to 20 years, he says, are also considered non-residents. Among them are a large number of people who have been displaced due to military operations in their native areas but they are facing discrimination here as well because they are not being recognized as residents of Lahore, he complains.

How many Pakhtuns were not counted?

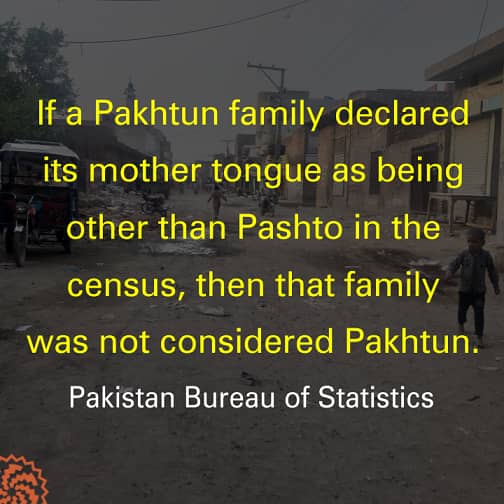

Saeed Ahmed, a Lahore-based assistant commissioner of the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, says mother tongue was determined during the 2017 census on the basis of the information provided by people. “This means we did not automatically consider a family as Pakhtun if it declared that its mother tongue was not Pashto but some other language,” he explains.

So, he says, if a linguistic group complains that the census did not show its correct number then it could be because its members did not declare their mother tongue as such. In this case, he adds, the census staff cannot be blamed.

Ahmed also clarifies that the 2017 census was not conducted on the basis of permanent addresses given in national identity cards. Rather, he says, it was not necessary for the census staff to view anyone’s identity card before including them in the population. “A person who has been living in the same place for six months was considered a resident of that place,” he says. The census staff could have demanded to see identity cards only if they felt that the information being provided to them was exaggerated or fraudulent, he adds.

He, nonetheless, acknowledges that the census staff was instructed not to count those in Lahore’s population who had moved here from the tribal districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa due to military operations. In the light of these instructions, he believes, “such people living in Lahore were counted in the population of their native areas.”

Based on his confession, it can be safely said that not all Pakhtuns living in Lahore were counted in the city’s population in 2017. But the question is: what is their actual number?

Ahmed suggests the number of such people could be in thousands but not in millions. In his own words, “the Pakhtun population of Lahore in the census certainly looks a little less than its actual number but the difference is not as big as being claimed by Pakhtun nationalist parties.”

Published on 27 Sep 2021