Hassan Naqvi, 30, traverses a little under 40 kilometers daily using a locally-manufactured electric motorcycle. He lives in southern Lahore's Khayaban-e-Amin residential area and works in Johar Town, about 17 kilometers north of his residence.

Naqvi says he decided to buy an electric motorcycle because of constant increases in petrol prices in the last couple of years. Now his family has three of them but charging them causes an almost inconspicuous addition to the family’s monthly electricity bill.

He, though, is not sure if he is making any savings. "The cost to replace inefficient batteries and chargers used in electric motorcycles nullifies what I save in fuel costs," he says. "The estimated annual petrol price for covering a daily distance of 40 kilometers is 84,000 rupees but the cost of annual replacement of five batteries used in one motorcycle, combined with the bi-annual replacement of chargers, is also roughly the same," he says.

According to him, the other problem with driving an electric motorcycle is its limited range. "If I charge it for six hours a day, it can only cover 50 kilometers," he says. In case of unusual route changes or emergencies, the absence of infrastructure to recharge it quickly makes it a frustrating choice, he explains.

Pakistan's National Electric Vehicle Policy, prepared in 2019, also underscores this problem and discusses a progressive rollout of this infrastructure: from major cities to motorways and highways. Since the launch of this policy, though, no visible efforts have been made to lay out the charging network. The major reason for this inaction is a dilemma: to set up the infrastructure first or wait until a reasonable number of electric vehicles are on the road. If the infrastructure is there, but there are not enough vehicles around to use it, then it will not be a financially viable option for those who have invested in it. On the flip side, not enough people will be incentivized to buy and use electric vehicles without a charging infrastructure.

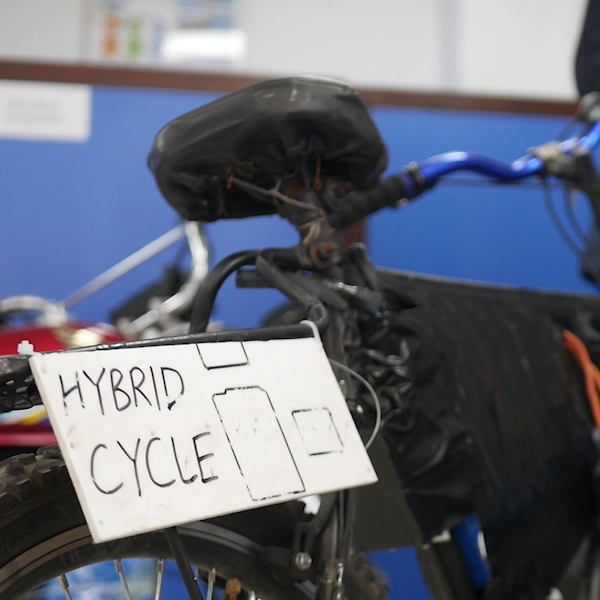

Researcher at the University of Lahore converting petrol motorcycle to an electric bike

Researcher at the University of Lahore converting petrol motorcycle to an electric bikeDr. Aazir Anwar Khan, director of the Integrated Engineering Center of Excellence at the University of Lahore, argues that the infrastructure needs to be built first, and the government should bear its cost. His calculations suggest that running 418 electric vehicles (a combination of motorcycles, rickshaws, cars, buses, and trucks) will require 16 charging stations across Pakistan. These stations, according to him, can be built with 4.4 million US dollars while their total running cost will be 960,000 US dollars. Since the production or retrofitting of the vehicles will also cost roughly 15 million US dollars and research, quality control and market regulation for them will need 1.7 million US dollars, the total price tag of this infrastructure will be 22 million US dollars, he says.

He, however, says all this cost will be recovered within seven years because running these 418 vehicles on petroleum would cost slightly less than three million US dollars each year. Running them on electricity will save all this money, he says.

Furthermore, if this charging infrastructure uses only renewable sources of energy – such as solar and wind – then this will result in even higher savings due to a reduction in environmental pollution, allowing the country to recover the cost of laying out the charging infrastructure in only five years, Khan reckons.

Capital costs versus fuel costs

These reported benefits notwithstanding, people in Pakistan seem reluctant to shift to electric vehicles. Though exact statistics are hard to come by as they are not being collected through any centralized system, the total number of electric motorcycles plying in the country would be barely a few thousand. The number of electric cars is not even in the hundreds; hardly any buses or trucks are running on electricity.

The public reluctance to not buy electric vehicles is mainly caused by the fact that electric vehicles cost way more than traditional vehicles. And, as Naqvi's experience suggests, people experience 'range anxiety’, the fear that their vehicle will run out of battery before reaching their destination.

Khan believes that Pakistan needs to overcome this reluctance as early as possible for reasons other than the environmental benefits of electric vehicles: an ever-widening gap between its imports and exports. This gap - called trade deficit - means that Pakistan's dollar earnings through selling products and services to other countries are much lower than its expenditure on buying products and services from abroad.

A LUMS Energy Institute report – published in 2019 and titled Electric Vehicles in Pakistan: Policy Recommendations – says that a sizable portion of this deficit (or 3.3 billion US dollars as of August 2022) is caused only by petroleum imports. In a business-as-usual scenario, petroleum imports will amount to 30.7 billion US dollars in 2025, which, in turn, will further increase their contribution to the trade deficit. He, therefore, argues that Pakistan needs to introduce electric vehicles immediately to bring down its petroleum imports and decrease its trade deficit.

Hafiz Owais Ahmad, a research associate at LUMS Energy Institute housed at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), says another possible financial benefit of electric vehicles is that they can help Pakistan get rid of the capacity payments. These charges are paid to the private sector's electricity generation plants which can produce more electricity than is purchased from them.

Consequently, the government pays them to maintain their extra capacity so that it can be utilized if and when the demand for electricity rises.

National Transmission and Dispatch Company (NTDC), a government entity that buys electricity from private producers and provides it to distribution companies, estimates that Pakistan will have an excess electricity production capacity of 15000 megawatts in 2025, costing the country 1500 billion rupees in capacity charges every year. Ahmad says introducing electric vehicles can absorb a large part of this excess capacity, thus reducing the payment of capacity charges. For instance, he says, bringing merely 500,000 electric vehicles to roads will cut this payment by 21 billion rupees.

Another LUMS Energy Institute report, Developing EV Infrastructure Across Highways and Motorways of Pakistan, talks of another benefit of electric vehicles. It says that running the country's entire mechanized ground transport on electricity will cause 63 per cent less emissions of hazardous substances when compared wheel to wheel with other vehicles, consequently reducing healthcare costs for those affected by pollution and the money required for managing and mitigating the natural disasters caused by climate change.

Pledges and problems

Data released by an inter-governmental entity, International Energy Agency (IEA), shows that transport running on fossil fuels – such as oil and gas – accounts for 37 per cent of all global carbon dioxide (CO2) gas emissions. This gas is considered one of the main contributors to climate change.

Electric vehicles have long been touted as a solution to its emissions. It was under the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, however, that the long-running discussions on these vehicles turned into a pledge for their promotion.

This pledge became more specific subsequently. At a Conference of Parties (COP) – an annual meeting of the countries signatories to the Paris Agreement – held in Glasgow, Scotland, last year, 38 countries pledged to stop using all means of ground transportation running on oil or gas by 2040.

Also Read

How the use of coal in cement production is increasing carbon emissions in Pakistan’s air

Though Pakistan is not among those countries, its National Electric Vehicles Policy states that 30 per cent of all new cars and 50 per cent of all new motorcycles, rickshaws, and trucks will run on electric power by 2030. Khan calls this policy proposal a progressive step though he also believes that "it does not go deep enough."

One of his main concerns is that it does not clearly state how the targets set for introducing electric vehicles will be achieved because, as he puts it, “we do not have a concrete plan to implement this policy”.

He says the policy is also silent on developing quality standards for such vehicles and regulating their market, a flaw that could result in producing low-quality vehicles whose batteries and chargers will need to be changed frequently. These changes, as Naqvi already testifies, will easily negate the financial benefit of the reduced energy costs.

Other energy experts say the policy does not explain what type of electricity these vehicles should use. "Electric vehicles charged with electricity produced from fossil fuels may not produce any pollution while they are being driven, but the electricity they are using has already emitted pollutants in the environment during its production process," says Atif Pervez, a battery research scientist working in Toronto, Canada.

Zian Moulvi, a Lahore-based lawyer, specializing in the energy sector, also says that charging electric vehicles with electricity produced from fossil fuels only shifts the problem of poisonous emissions from the transport sector to the electricity generation sector. In a webinar early this month on Pakistan's transition to renewable energy, he argued that even hydroelectric power must be excluded from the energy sources used for charging electric vehicles. "The environmental, hydrological, and social problems caused by large-scale hydroelectric power plants far outweigh their supposed benefits," he said. He, therefore, wanted the government to promote the use of only alternative renewable sources (mainly wind and solar panels) for charging electric vehicles.

However, he complained that the government was not making any serious changes in its electricity production mix to promote electricity production through alternative renewable sources. To back his argument, he referred to the latest iteration of the Indicative Generation Capacity Expansion Plan (IGCEP 2021-30), a government document that explains which source will produce how much electricity in the next nine years. According to him, this plan indicates incremental changes in the share of energy produced through wind turbines and solar panels but only 11% of Pakistan's total electricity in 2030 will be produced by these two sources.

So, he argued, even a large-scale introduction of electric vehicles will not make any major difference to Pakistan's emission of poisonous gases in the atmosphere since they will still be charged with electricity produced with dirty technologies.

To Dr. Irfan Yousuf, on the other hand, all this criticism of the National Electric Vehicle Policy appears misplaced. He works as an advisor at the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (Nepra) and says the basic objective of this policy is to reduce the poisonous emissions of the transport sector. This objective, he argues, cannot be achieved without synching it with the government's policy to produce electricity from alternative renewable sources.

So, in his view, introducing electric vehicles and increasing the share of electricity produced from alternative renewable sources should – and will – go hand in hand.

Published on 18 Sep 2022