Ameen Masih’s name has echoed in several legal proceedings since the Lahore High Court made a landmark decision in his favor in 2017 – but not many people know much about him.

A tailor by profession, he married Sonia Aziz in 2004 but, before long, their marriage took an ugly turn. She belonged to a family with a sizeable income so she found it difficult to adjust to his meager earnings. During 10 years of their marriage, says Ameen, they hardly lived together for two years. She would often stay with her parents where her family used to incite her against him over money, he says. Once back home, she would often ask him for a divorce but he was not ready to give up on his marriage because he considered it a sacred union.

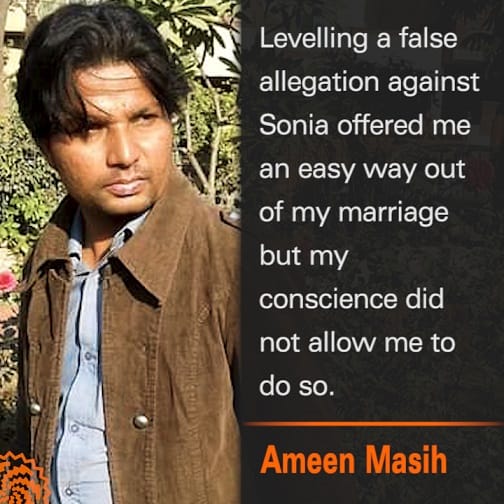

Also, the only ground available to him to divorce his wife under the Christian Divorce Act of 1869 was to accuse her of committing adultery -- which she had not. “Levelling a false allegation against Sonia offered me an easy way out of my marriage but my conscience did not allow me to do so,” he says on a recent Sunday.

Another reason why Ameen thought that he should keep his marriage going was his daughter, Shiza. He knew if he had accused Sonia of being an adulterous, it would have an impact on Shiza too. Nobody would want to marry her and questions would always be raised about her character as well, he says.

But he also knew that his frequent fights with Sonia were similarly unhealthy for his daughter’s emotional and psychological development. So, he and his wife decided to part ways amicably.

He, then, approached Sheraz Zaka, a Lahore High Court lawyer whose mother and sisters were his old customers, to seek his advice on how to go about it without mentioning adultery. When, subsequently, he submitted a petition at the Lahore High Court in 2016, he carved a new path and sought the restoration of Section 7 of the Christian Divorce Act.

This section allows Christian couples to seek and get divorces under the UK Matrimonial Causes Act after an “irretrievable breakdown” of their marriages caused by any reason other than adultery. The government of General Ziaul Haq, however, had removed it from the act in 1981.

Ameen contended in his petition that the removal of Section 7 was unconstitutional and violated the fundamental rights of Christians living in Pakistan. He also argued that it was forcing Pakistani Christians to convert to Islam in order to divorce their spouses.

Pros and cons

During the hearing of the petition, the court summoned Dr Alexander John Malik, Bishop Emeritus of Lahore, who was also the Bishop of Lahore during Zia’s era, to testify. He informed the court in a written statement that Section 7 was removed without consulting any Christian religious leaders. Supporting Ameen’s petition, he also said the section’s removal had made the Christian Divorce Act “restrictive and violative of Human Rights”.

Hina Hafeezullah Ishaq, assistant attorney general of Pakistan at the time, presented the same argument while appearing in the court on the behalf of the federal government. She said the section’s removal was repugnant to the women’s basic rights guaranteed by the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) that Pakistan has signed. She, therefore, argued that the deletion of the section violated Article 8 of the constitution which invalidates any law or custom or usage that is inconsistent with fundamental rights.

She also said that although Article 227 of the constitution guarantees that all existing laws will conform to Islamic edicts, this provision is not applicable to other faiths. So, she concluded, there should be no hurdle in restoring Section 7.

Human rights activist Hina Jillani, Shunila Ruth and Mary Gill, both Christian members of the Punjab Assembly at that time, and Fauzia Viqar, chairperson of the Punjab Commission on the Status of Women, also fully supported Ameen’s petition. Jillani argued in the court that the deletion of Section 7 by a presidential ordinance violated the constitution’s Articles 9 (which protects the life and liberty of a person), Article 14 (which guarantees dignity of person and privacy of home) and Article 25 (which makes all citizens equal regardless of their gender, caste, creed and ethnicity etc).

Khalil Tahir Sandhu, Punjab’s minister for human rights and minorities affairs, as well as several priests from all the major Christian denominations opposed the petition. They stated that a Christian marriage is a sacred union as per the biblical edicts and, therefore, cannot be annulled on any grounds except adultery.

On 19th June 2017, Justice Mansoor Ali Shah, who heard Ameen’s petition, finally gave his verdict. He restored Section 7 and noted in his judgment that its omission was a “regressive” step “driven by oblique ends by the undemocratic regime of the past”. He also stated that the deletion of the section “not only obstructed and frustrated the minority rights but also went against the grain of international obligations entered by the State by ratifying International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Principles of Policy under the Constitution.”

Justice Shah stated that “no-fault divorce or irretrievable breakdown of marriage is an established ground of divorce in Christian majority countries of the world.” Such a divorce, he said, would allow a married couple “to avoid presenting sordid and ugly details in the court, strengthen and preserve the integrity of marriage and safeguard family relationships.”

A few weeks after Justice Shah announced this judgment, Emmanuel Francis, a Christian citizen, filed an intra-court appeal against it. Many eminent Pakistani Christians supported his appeal. They all believed that the statements given by the members of clergy during the hearing of Ameen’s petition were not given due consideration. They also contended that no worldly legislations could replace or contradict the Bible’s teachings.

As Kashif Alexander, a Lahore High Court lawyer who also heads an association of Christian lawyers, puts it, the restoration of Section 7 violates Article 20 of the constitution which declares that “every citizen shall have the right to profess, practice and propagate his religion”. He, therefore, believes that Justice Shah has given “a discriminatory judgment” which, according to him, is a “direct interference” in minority affairs.

Alexander also argues that the restoration of Section 7 has made British laws applicable in Pakistani courts. “Since Pakistani Christians are citizens of Pakistan, it makes no sense that a British law is applied to them,” he says.

Another argument that he offers against the restoration of the section is that parliament, not courts, are the right forum for changing or rectifying a piece of legislating. If the Christian Divorce Act requires amendments, he says, a parliamentary committee should have held formal and detailed consultations with the leaders of Christian community before drafting and approving those amendments.

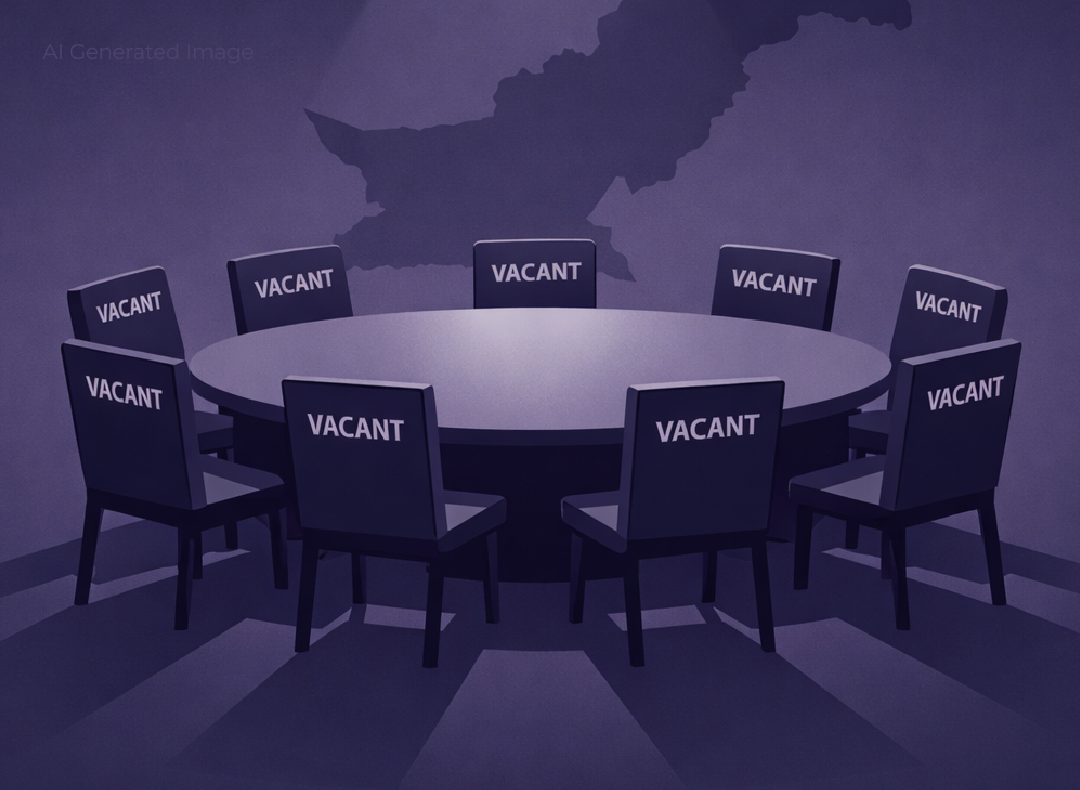

Except that such a consultation, indeed, has already taken place but a proposed Christian Marriage and Divorce Act is still pending passage by parliament only because Christian clergy does not approve of it. Many prominent Pakistani Christians, therefore, do not agree with Alexander’s point of view that a judicial remedy should not be available to Christian couples caught in bad marriages.

Also Read

The cross on their little shoulders: Kidnapping and forced marriages of Christian girls in Pakistan

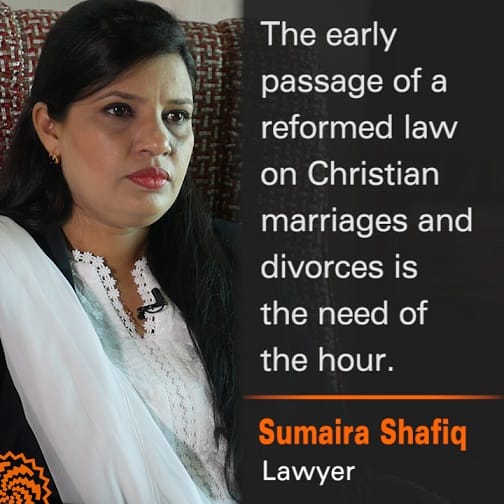

Sumaira Shafiq is one of them. A lawyer based in Lahore agrees that the early passage of a reformed law on Christian marriages and divorces is the need of the hour -- not because courts are inappropriate forums to do so but in order to further legitimize their rulings. “The judgment of a provincial high court is not applicable in the rest of the courts,” she says. “Changes in the laws, therefore, should be approved by parliament so that anyone can utilize them anywhere they need.”

All is well that ends well

Sheraz Zaka ensured throughout the court proceedings on Ameen’s petition that his client did not have to appear before the court. This allowed Ameen to keep his identity secret. In turn, this would help him start his life afresh -- without having to worry about any stigma resulting from a divorce that clergy is unhappy about.

So, following the Lahore High Court verdict in his favor, he left his old job and his old house and moved to another city. His mother chose another woman, Arfa, a Catholic Christian, to be his wife. They soon got married.

Divorce is forbidden in Arfa’s denomination too but, she says, she had no objection to marrying a divorced man. She actually respects Ameen because, as she says, he did not lose his humanity and accuse his first wife of adultery even when his marriage with her was broken beyond repair.

Ameen himself feels relieved that he did not have to lie about his first wife’s character in order to leave her. “I would never be happy if I had ruined her life,” he says.

Sonia, too, has remarried and, according to Ameen, is happy with her new life. “This would not have been possible if I had wrongfully accused her of adultery.”

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 14th July 2021, on its old website.

Published on 17 Feb 2022