Heads of states and governments from across the globe gathered in Glasgow, Scotland, to discuss the issue of climate change. Known as the Conference of Parties (COP), this summit started on 31st October and concluded on 12th November.

Since this was the 26th such annual conference, it has been named as COP-26. Its participants included all those countries that have signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Organized by the United Nations, it took place in the wake of a report released in August this year by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also put together by the United Nations. This report has warned starkly that human activities are making the Earth dangerously hot and that climate change has assumed such serious proportions that, if some urgent steps are not taken to mitigate it, this planet will become uninhabitable by the end of this century.

The COP-26, therefore, concentrated on the following objectives:

1. To take concrete steps to achieve global Net-Zero by 2050 so that all the environment-unfriendly carbon being produced is eliminated from the atmosphere; to take steps to ensure that the increase in global temperature does not go above 1.5 degree Celsius

2. To enable human settlements and natural habitats across the world to adapt to the adverse effects of climate change

3. To mobilise financial resources for vulnerable countries so that they can better handle the impacts of climate change

4. In order to achieve these objectives, a global consensus among governments, business entities and civil society be developed so that a joint strategy can be put together to mitigate the consequences of climate change.

These are, more or less, the same objectives which were set out in the Paris Climate Accords -- known as Paris Agreement -- in 2015. That accord, for instance, too, set a target of keeping the rise in global temperature within 1.5 degrees Celsius.

While it apparently contains everything that is essential to tackle climate change, this agreement has a major drawback: it does not make it obligatory for governments to take the required steps. It also does not set any mandatory targets for reducing the emission of gases responsible for global warming.

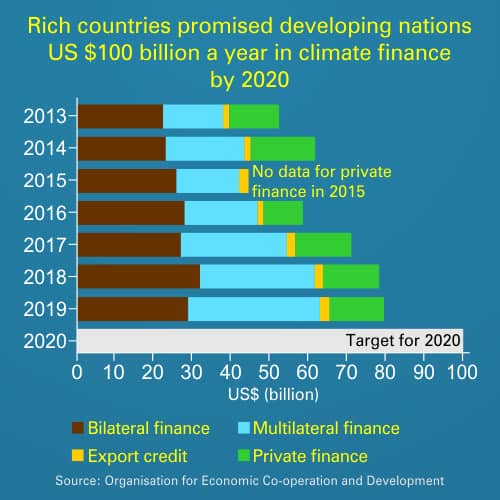

Then there is another problem with the agreement. Its Article 9 stipulated that t the countries with the largest economies shall spend 100 billion dollars annually till 2020 on tackling climate change. The main chunk of this money was supposed to go to the developing countries.

But statistics relevant to this money reveal that the developed counties gave only 79.6 billion dollars to the developing countries in 2019 -- the largest amount given in a calendar year since the former countries first pledged it in 2013. The numbers for 2020 are not yet out but experts believe that its target might have been missed too. They, in fact, fear that due to the Covid-19 pandemic the money spent on climate change in the last year could be even less than that spent in the previous years.

Who is paying how much?

The Paris Agreement did not determine the share of each country in the 100 billion dollars committed by the developed economies. If, however, the respective population of donor countries, their wealth and their economic activities which lead to the emission of gasses causing global warming are taken into consideration, then the United States should have contributed 40 per cent to 47 per cent in it.

But the ground reality is starkly different.

The World Resource Institute, a leading organization that collects data on climate change and other related issues, says the United States disbursed an average of 7.6 billion a year between 2016 and 2018. Australia and Canada have also failed to meet their targets. And, though, Japan and France have contributed more than their fair share, they have given a larger part of this amount in loans and not as grants.

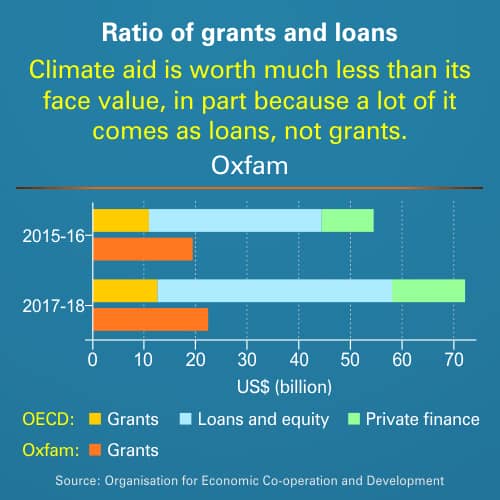

An international donor agency, Oxfam, seconds this. It says the amount given by the developed countries to the developing countries to deal with climate change is much less than it is projected to be because it mainly consists of loans, not aid, and is thus increasing the financial burden of the recipient countries.

The developing countries also say 100 billion dollars a year are not enough to cope with the effects of climate change. On July 8th this year, finance ministers of these countries held an online meeting. They stated in that meeting that since the developed countries did not fulfil their earlier commitments, they should now pay 500 billion dollars by the end of 2025 – all in the form of cash grants.

Some developed countries, indeed, announced even before the COP-26 summit that they will meet their targets in the future. In June 2021, for example, Canada, Japan and Germany announced at the G-7 summit that they would ensure the provision of 100 billion dollars every year to the developing countries till 2025.

Likewise, in September 2021, the European Union pledged that it will provide 5 billion dollars every year till 2027 in addition to its earlier commitments. The United States President Joe Biden, too, has announced that his country would disburse 11.4 billion dollars annually till 2024.

Given the past experience, though, it is pertinent to ask: will the developing countries trust these promises?

Experts say the veracity, or otherwise, of these promises will be assessed in COP-26. This conference will not only discuss the unhonoured commitments but the rich countries participating in it will also promise how much financial resources they will provide in this regard after 2025.

Barriers to achieving climate targets

The factors responsible for the failure to achieve the targets set for controlling climate change are complex. Many experts, however, believe that one of its main reasons is the absence of a focus on climate justice in all the debates about it so far. They, therefore, say the success of COP-26 depends on whether there is a serious discussion on the issue of climatic inequalities or not.

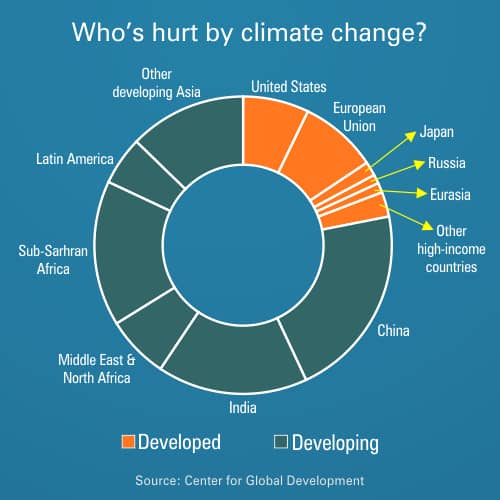

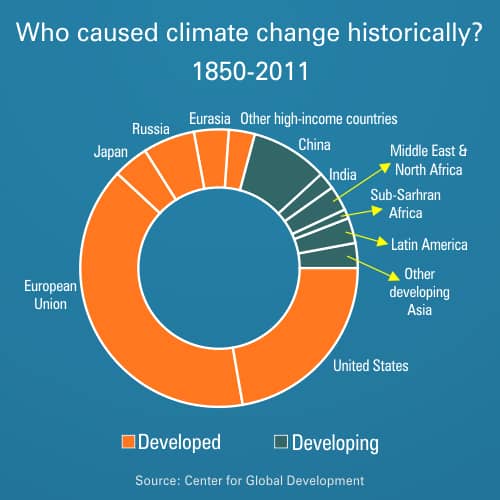

The main reason why this issue has not been taken seriously so far is that the countries playing a central role in global negotiations on climate change are the ones that emit the most amount of carbon but are relatively less affected by climate change. This explains why they are disinterested in reducing the emission of gasses responsible for global warming.

On the other hand, the countries that are being severely affected by the negative effects of climate change -- but have a smaller role in global warming -- are not considered important in international negotiations mainly because most of them are economically small and backward.

Talking about this inequality, Isaac Stoddard, a meteorologist working at the University of Uppsala in Sweden, says: “The richest one per cent of the world’s population emits twice as much carbon as half of the world’s population. The 10 per cent richest population of the world is responsible for more than half of the world’s total carbon emissions.”

Stoddard and several other researchers have published a study recently in an academic journal, Annual Review of the Environment and Resources.

They say climate change is, in fact, just a symptom of an economic and social crisis that originates from an unjust and unsustainable global political economy. They say the centralisation of economic and political power in the hands of the developed countries prevents us from transforming the world and our own societies in such a way that we can rapidly reduce carbon emissions.

Anju Sharma, an environmentalist from India, is among these researchers too. She also represented India at the first Summit on Climate Change held in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan. She says the accumulation of power and authority in the hands of the developed countries and their failure to ensure climate justice is also evident from the fact that the entire problem has to be discussed under the auspices of the United Nations.

Sharma also says the developing countries wanted to address the issue of climatic inequality even at the Kyoto conference and they also made some serious suggestions in this regard. But the United States kept on opposing those proposals throughout the summit, she says. “We were told time and again that if we talked about the issue of equality, the developed countries will not take the responsibility to solve this problem,” she adds.

Also Read

Global warming: An international panel of scientists identifies the most lethal threats to life on Earth

But the persisting demands by the developing countries made the then-United States Vice President Al Gore to hold a press conference towards the end of the summit in which he said that he would ask his team to show some flexibility. This makes Sharma to conclude that all the decisions on global climate issues are subject to the whim and fancy of the world’s major powers.

Another main reason for an unequal debate on climate change is that those participating in it from the developed countries are highly qualified and vastly experienced while the developing countries lack such human resources.

For example, the United States’ delegation to the Kyoto Conference had many climate change experts who were accompanied by lawyers and economists with specialized skills. India, on the other hand, was represented by only three people. Similarly, many African countries had only one participant each taking part in those highly technical negotiations. This way a number of proposals that could have helped solve some of the most serious climatic issues were rejected owing to the dominant role of the United States and other developed countries.

Sharma and her team, however, still succeeded in convincing the Indian government to resist the demands of the developed countries by founding and leading a bloc of the developing countries. In the end, however, the developed countries prevailed and the then-American President Bill Clinton spoke directly to India’s environment minister and later with its prime minister, urging them to soften their stance.

Published on 15 Nov 2021