Residents of Natt Kalar suspected that some of their fellow villagers had become addicted to some powerful drug.

These villagers worked at a nearby factory and seemed completely normal on Thursday evenings when they would come back home for a weekly holiday. On Fridays, though, they seemed to be experiencing serious withdrawal symptoms. Totally devoid of energy, they would not leave their beds throughout the day and would not have the strength to walk even to a corner shop. As soon as they returned to work the next day, though, all their energies would come back.

After spending almost two years in this situation, these laborers started to develop severe difficulties in breathing. This problem then aggravated to such an extent that it became difficult for them to even get up, walk and work.

Soon, they began to die -- one after another.

Over the last 15 years, 14 of them have lost their lives while three more await death.

Deadly working conditions

Located in Kamoki tehsil of Gujranwala district, Natt Kalar consists of around 150 households. Some of the families living here lost their agricultural income in the early 2000s following a land dispute with a local member of the National Assembly. This forced several men from these families to seek work in nearby towns and cities – with some getting jobs at a stone grinding factory, owned by one Muhammad Ashraf Ansari and located close to Lohianwala bypass in Gujranwala city.

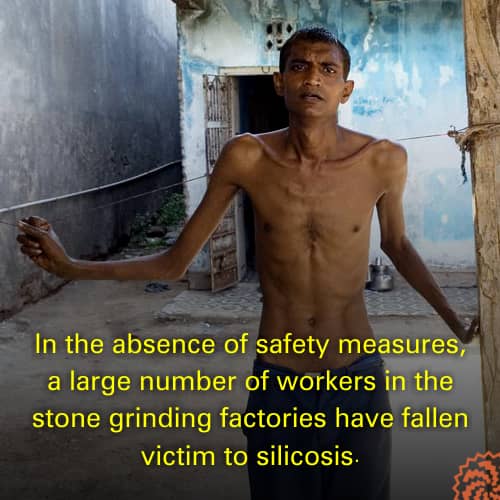

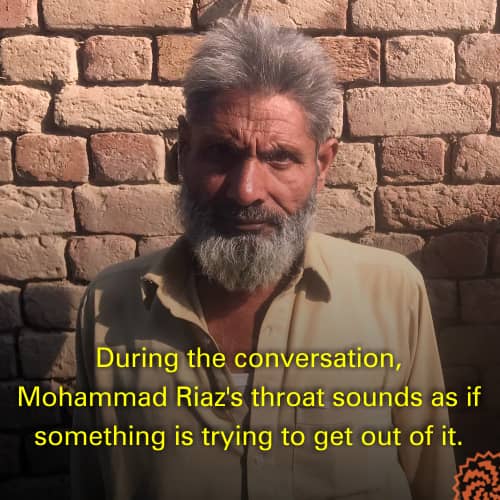

Muhammad Riaz was one of these workers.

On a November evening in 2021, he is sitting in his living room in Natt Kalar. The grey walls of the room are not painted and a worn-out carpet covers half of its uneven cemented floor. Riaz says he is about 55 years old but he looks much older. He talks in short sentences because every few words he speaks are followed by a fit of cough. While he talks and coughs simultaneously, it seems as if something is boiling in his throat and is struggling to get out.

He has been suffering from these problems since 2006.

Riaz says he – as well as other workers from his village – would grind stones and mix boric acid in the powdered stones often with their bare hands. They would later put the mixture in sacks with shovels.

His brother, Muhammad Shahbaz, used to work the same way. He had not yet completed two years of his job at the factory when he suddenly became extremely sick. He would often have high fever, his cough would hamper his speech and he would run out of breath after a short walk. He soon lost his job because his condition would not allow him to do any work.

Doctors told him that he had contracted tuberculosis but his condition continued to worsen despite using medicine prescribed to him. He then died in 2007 -- before his illness could be properly diagnosed.

Before his death, some other factory workers from his village also started experiencing similar medical symptoms. Many of them would die over the next five years.

A professional hazard

Usama Khawar, who also belongs to Natt Kalar, was studying law at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) in 2012. That summer, he went back to his village for a vacation and found that people there were dying after developing the same medical symptoms.

He contacted several doctors – operating around Natt Kalar as well as in Lahore -- to probe the nature of the disease. He also did some internet research on his own and found that the ailment they were suffering from was silicosis.

He then took two of these patients to Lahore for diagnosis and treatment in 2014. Dr M A Javed Siddiqui and Dr Khawar Abbas Chaudhary, both working at a private hospital, Surgimed, later confirmed that these patients, indeed, had silicosis.

All patients belonging to Natt Kalar had previously sought treatment from Dr Munir A Bhatti, a pulmonologist who runs a private clinic behind a police station on Imam Sahib Road in Sialkot city. According to him, one of the main reasons why it took so long to diagnose the disease was that “in the whole of Punjab, the equipment and technical skills required for its diagnosis are available only in Lahore”.

Dr Abdul Wajid Khan, who heads the pulmonology department at the Central Government Hospital in Sialkot, confirms this: “Facilities such as lung biopsy and bronchoscopy required to diagnose silicosis are not available in any local hospital in Sialkot or Gujranwala”.

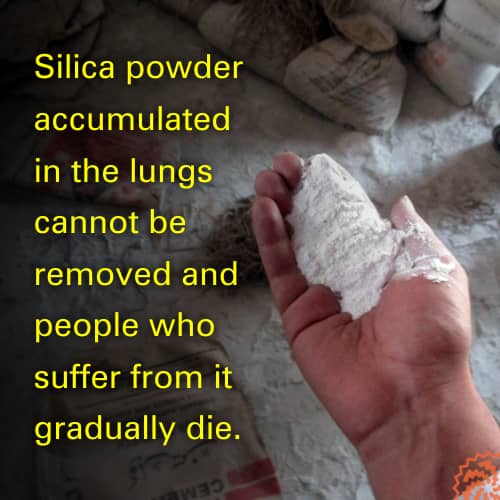

World Health Organization (WHO) and International Labor Organization (ILO) consider silicosis to be an “occupational disease” which only affects people working under certain conditions. It cannot be contracted by anyone else.

Dr Bhatti says factory workers get silicosis while working on stone-grinding, glass-making and acid lining because in these professions they become exposed to silica dust (which gets suspended in the air as a result of these industrial operations). As this dust accumulates in their lungs through the respiratory tract, it reduces their ability to absorb oxygen, he says. “There is no cure for this disease because silica particles trapped in lungs cannot be removed,” he adds. Consequently, those who suffer from silicosis, die slowly and painfully.

Medical experts say it is necessary to install air purifiers and vacuum cleaners in factories so as to remove silica dust suspended inside them. They also say it is necessary for those working in stone-grinding factories that they cover their faces with masks and protect their hands with gloves to avoid contracting the disease.

Dr Bhatti, however, points out that the mere fact that a worker has contracted silicosis is a proof that his workplace does not have any of these protective measures in place.

Crime and punishment

Khawar and the families of silicosis victims in his village filed a petition at the Lahore High Court in early 2014. In this, they asked the court to set up a commission to investigate the deaths caused by it.

When no serious action was taken on their petition, Khawar sent an application to the Supreme Court of Pakistan on July 1st, 2014, asking it to take suo moto cognizance of the matter. His request was granted. On April 14th, 2015, the Supreme Court directed the Punjab government to immediately inspect stone grinding factories to find out the safety measures they were taking – or not taking -- for their workers.

The next day, Zaigham Abbas, the then director of the provincial labor department in Gujranwala, and his subordinates raided five large factories in the city. These raids revealed that four of these factories had absolutely no safety measures in place. In fact, none of them had a government-issued license to grind stones. They also had not obtained any no-objection certificate from the Environment Protection Agency for their operation.

Abbas and his staff were not allowed to enter the fifth factory, Master Tiles, which was – and still is – among the largest stone grinding units in Gujranwala. According to a report submitted to the Supreme Court by Punjab’s labor department, when the raiding party reached the factory’s gate, its management locked it from inside. Despite this blatant violation of the court orders, however, no action has been taken against the factory.

Later, in 2018, the same department told the Supreme Court that it had carried out 591 inspections in factories around Punjab in the previous year and took action 15 times against the delinquent ones among them. But the total fine imposed in all these cases was as meagre as 35,000 rupees.

Also, the department still does not have a complete record of stone grinding factories in Punjab. Only once in 2014, and that too at the behest of the Supreme Court, more than 100 such factories were identified across the province. They have never been counted before or after that.

When this record was presented in the Supreme Court, it also contained the shocking revelation that more than 80 per cent of stone grinding factories in Punjab were operating without any official registration or license.

Data deficit

According to the government figures, more than 100 people have died in Punjab in the last one decade from occupational diseases related to lungs. Many of them died of silicosis, with 34 of them belonging to a single village, Chak Nangar, located in Dera Ghazi Khan. Even now, at least 400 people are suffering from this disease in different parts of Punjab.

A large number of these patients live in Gujranwala division and they have worked in dozens of stone grinding factories in and around Gujranwala city.

But these official figures, published by the Directorate General Health Services (DGHS) Punjab, are neither final nor completely accurate. The first problem in them is that no government department had ever maintained any record of silicosis patients in Punjab before 2014.

Another problem with these numbers is that they are based on the patient data taken from the government hospitals in the province. Since most of these hospitals do not have the equipment and skills required to diagnose silicosis, many of the patients visiting them continue to suffer from undiagnosed silicosis. Similarly, those being diagnosed and treated at private hospitals are not included in these statistics.

There are also many serious errors in this data. For example, the DGHS annual report for 2015 states that the number of silicosis patients in Punjab reached 467,505 in that year. This was thousands of times higher than their number in the previous year. Head of the Punjab health department’s information management systems says the number was inaccurate and was “clearly included in the report as the result of a typographical error”. Six years later, however, the error is still to be rectified.

Factories of death

In the wake of news reports that 34 workers had died after contracting silicosis in Dera Ghazi Khan district, the then Punjab Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif formed a special investigation team in 2012 to look into the matter. This team not only confirmed these deaths, it also pointed out that 134 other people were still suffering from the same disease in the same settlement.

Khawar, in the meanwhile, visited six different localities in Punjab and found out that more than 100 workers had succumbed to silicosis there. Based on his findings, he later expressed a concern at the Supreme Court that “if Muhammad Ashraf Ansari's small factory…can cause fifty deaths, then considering that there are thousands of stone factories in Pakistan employing thousands of workers, the number of people being killed each year must be in thousands.”

To address this problem, the investigation team appointed by the chief minister recommended that factory owners and government officials responsible for deaths from silicosis be prosecuted on the charges of criminal negligence and that workers suffering from the disease be compensated by their employers. So far, though, no lawsuit has been filed against any factory owner and no significant amount of compensation has been paid to the affected workers.

The only outcome of all these proceedings is that Muhammad Ashraf Ansari has shifted his factory from Gujranwala to Daska tehsil of Sialkot district. Similarly, only 300,000 rupees have been given to the relatives of each laborer who died of silicosis. Not a single penny, though, has been paid to the patients who are still alive.

Riaz, on the other hand, says his monthly medicine alone costs around 20,000 rupees. He also needs thousands of rupees every month to run his household. Since he can no longer do any paid work, he has been dependent on his extended family and other villagers to meet these expenses.

Carrying a plastic bag full of medicine, he recalls how an elderly woman in the early days of his job used to stop him and other workers every day at the factory’s main entrance. She would warn them: “This factory has consumed my seven sons; it will eat you up too”.

The workers used to regard her as insane so they never paid any heed to her.

But Riaz admits 17 years later that “we should have listened to her because the factory has actually consumed us all too”.

Published on 15 Dec 2021