Former Brigadier Shuja Hassan’s appointment as chief executive officer of Pakistan Steel Mills last week is the most recent instance of the deployment of serving and retired military officers in civil institutions.

Only days earlier, Major General Amer Aslam Khan and Brigadier Nasir Manzur Malik were appointed to work respectively as the deputy chairman and executive director of Naya Pakistan Housing Project. The recent announcement by the federal government that the military and its affiliated institutions, such as Frontier Works Organization (FWO), will work on improving Karachi’s sewerage and sanitation system can also be seen as another example of the military’s expanding footprint into the civilian domains.

Many in Pakistan do not see any problem in that. They argue that, apart from religion, military is the only glue that is keeping today’s Pakistan together (though they seldom acknowledge that both these factors failed to stop East Pakistan from becoming Bangladesh in 1971). Otherwise, they contend, some parts of Pakistan might have already gone their way – just as Bangladesh did – due to ethnic and geostrategic reasons.

A Lahore-based political analyst, Dr Saeed Shafqat, who has written extensively on civil-military relations in Pakistan, argues that, within the current institutional landscape of Pakistan, only the military has been able to portray its self-interest as the national interest. “And in doing so, it has been able to secure the position of the savior.”

There is also no dearth of people who believe that the military is an island of excellence in a sea of mediocrity. After all, they say, it is a highly disciplined and efficient institution which, many a time in the past, has worked on rescue and relief work during natural disasters and ran administrative and justice systems in troubled parts of our homeland.

They cite the examples of Air Marshal Asghar khan and Air Marshall Nur Khan who are said to have successfully run the state-owned Pakistan International Airline (PIA) in the 1960s through to the 1980s. In the same vein, the names of some former military men are also dropped when it comes to the running of the country’s beloved sport, cricket. Nur Khan gets a prominent mention in this regard too – as he does with reference to the administration of Pakistan’s national game – hockey.

Other military officers to have headed Pakistan’s cricket administration include Lieutenant General (retired) Khwaja Muhammad Azhar, Lieutenant General (retired) Ghulam Safdar Butt and Lieutenant General (retired) Zahid Ali Akbar Khan (who later pleaded guilty for embezzling 200 million rupees as the head of Water and Power Development Authority – Wapda) and Lieutenant General Tauqeer Zia who was director general military operations during the Kargil War in 1999.

Wapda, too, has been a familiar domain for senior military officials. Both Ghulam Safdar Butt and Zahid Ali Akbar Khan have worked as its chairmen – as has Lieutenant General Zulfiqar Ali Khan (who, in 2002, also headed Pakistan’s contingent for Commonwealth Games held in Manchester). He also headed another civilian institution, Evacuee Trust Property Board, in 2000s (and was once accused by the National Assembly’s Public Accounts Committee of causing a loss of more than 2.4 billion rupees to the national exchequer).

Not so surprisingly, the trend of appointing serving and retired military officers to civilian jobs increases during military regimes though it is certainly not limited to them. General Ayub khan, General Yahya Khan, General Ziaul Haq and General Pervez Musharraf – the four military rulers that Pakistan has had so far -- all assigned important civilian posts to their trusted military colleagues.

Major General (retired) Sher Ali Khan Pataudi was Yahya Khan’s information and broadcasting czar, so was Lieutenant General Mujeebur Rehman during Zia’s regime. Bother Major General (retired) Sahabzada Yaqub Ali Khan and Major General (retired) Rao Farman Ali Khan has worked as central ministers under Zia. During Musharraf’s rule, he appointed military officers also as the vice-chancellors of universities and as heads of the National Accountability Bureau (NAB).

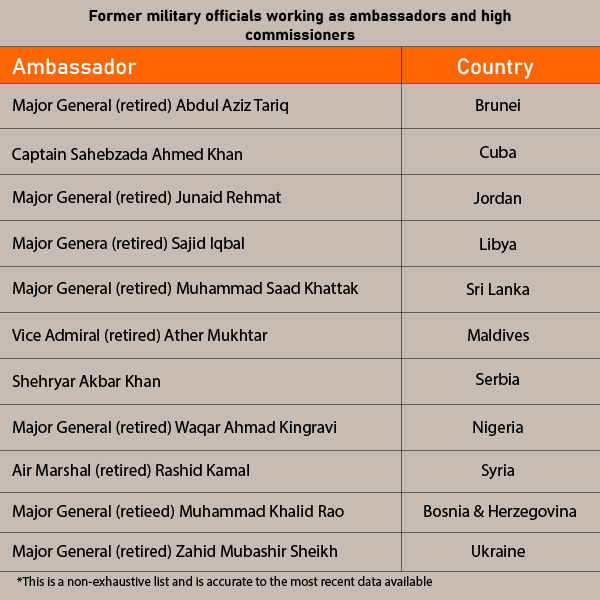

Civilian governments, too, have relied on military officers to do important assignments – including ministerial responsibilities. Pakistan’s two consecutive national security advisors under the governments of Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz between 2008 and 2018 were retired generals. The foreign minister in Benazir Bhutto’s first government (1989-90) was also a retired general.

Some ostensibly civilian institutions – such as National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and National Institute of Health (NIH) – are also being led by serving generals – while Pakistan Telecommunication authority, Wapda and PIA are being run by retired military officers.

Khaki over mufti

Military’s intervention in Pakistan’s civilian sphere has been a classic chicken and egg story. Which one came first: a strong military or a weak civilian polity?

Long before General Ayub Khan imposed martial law in 1958, he would sit in cabinet meetings without having a ministerial portfolio. Pakistan’s first president, Iskandar Mirza, was also a military man turned bureaucrat. In those early days, there had been numerous other instances of the military moving political strings from behind the scenes – such as when Governor General Ghulam Muhammad was forced to quit by Ayub Khan in 1955.

Even after the long military rule that Pakistan experienced between 1958 and 1988 – with a brief civilian interregnum of seven years – ended, civilian politics was always overshadowed by men in khaki. And then General Pervez Musharraf imposed another military regime in 1999.

In 1988, the then army chief General Mirza Aslam Beg was instrumental in ensuring that the government of Prime Minister Muhammad Khan Junejo was not restored even though the Supreme Court had declared its dissolution as unconstitutional. Beg also overtly supported President Ghulam Ishaq Khan when he removed Benazir Bhutto’s first government. Later, he would oppose the civilian government’s policy to support American war effort against Iraq in 1992.

His successor Asif Nawaz Janjua never had an easy relationship with Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. The next army chief Waheed Kakar went on to play the role of ultimate arbiter of Pakistan’s politics when there seemed to be no other way out of a stalemate between President Ghulam Ishaq Khan and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif – he sent both of them home.

Next came the tussle between Nawaz Sharif and General Jahangir Karamat who supported the setting up of a military-dominated National Security Council to supervise Pakistan’s security and foreign policy establishments. The only not-so-unexpected denouement of General Karamat’s premature exit as army chief was the overthrow of Nawaz Sharif’s government by his successor.

That Karamat would become Pakistan’s ambassador to Washington DC under Pervez Musharraf only raised the same question again – was his appointment an effect of the military’s indisputable predominance of Pakistan’s polity or did it show that civilian politicians are too weak to fight off its dominance?

That is what brings us to the most popular argument in favor of deploying military officers in civilian affairs: that civil institutions are not just weak, they are also corrupt and inefficient.

As Dr Hassan Askari Rizvi, a political scientist based in Lahore who has also briefly worked as Punjab’s caretaker chief minister in 2018, says: “As long as civilian institutions do not build their own capacity and keep on calling the army for every little crisis that befalls them, we cannot move towards a state where we are less reliant on military than we are now.”

He blames Pakistan’s political divisions for being a major reason for an increased need for the military’s presence as a stabilizer. “Parties in government and opposition are spent fighting with each other so much that their fight weakens civil institutions,” he says. “Nearly every political party relies on the military during its own term in power but criticizes its rivals for doing exactly the same when it is in opposition.”

Dr Saeed Shafqat also puts the onus for an imbalance in civil-military relationship on political parties. “They have used democracy not to strengthen political system and institutionalize dialogue, delegation of power and parliamentary consensus etc but only as a rhetoric to come into power”.

Even more importantly, as many analysts have argued, political parties start to crawl when the military asks them to bend. For instance, no major political party objected to a recent change in the Army Act which has given the prime minister the power to extend the tenure of a serving army chief beyond his original date of retirement. Similarly, every political party voted in favor of military courts in 2015 when the military insisted that it wanted these courts to conduct speedy trials of suspected terrorists.

Under the current administration, this trend has only intensified. In recent months, there has been a rapid increase in the number of serving and retired military officials being given civilian assignments. Perhaps the most important of them is Lieutenant General (retired) Asim Saleem Bajwa’s twin appointments as the chairman of the recently sent up China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Authority and as a special advisor to the prime minister on information and broadcasting.

Even when the military intervenes and interferes in such civilian and political matters as holding of elections, the big parties never go beyond making press statements to complain about it. Citing ‘supreme national interest’ as the reason for their restraint, they never seek, or order, a thorough inquiry into these electoral manipulations.

Mehmood Khan Achakzai, a senior parliamentarian from western Balochistan, accuses both Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz and Pakistan Peoples Party – two of the oldest parties in the country – of harming the long-term development of democracy by sidestepping the question of the military’s meddling in elections. “But they must remember that history is brutal and it does not like dishonesty,” he once famously quipped.

This lack of resistance to the military can also be seen as a survival strategy for political parties. They, after all, have suffered heavily under various martial law regimes – having faced Elective Bodies Disqualification Ordinance (EBDO) under Ayub Khan, partly-less elections under Zia and lopsided and manipulative accountability under Musharraf. In between, one prime minister was hanged, another was overthrown in a coup, two were sacked by courts and still, others had their governments overthrown by ways and means of dubious constitutional vintage. Consequently, political parties have realized the importance of and the need for making compromises – just in order to stay in the political arena.

Also Read

Books versus bullets

Saeed Shafqat explains this institutional landscape by arguing that there is a “super-ordinate and sub-ordinate” relationship between the military and the civilians in the country. “It is not a predator-prey relationship,” he says and adds that this helps the military work effectively both with and within civil institutions.

It’s the money, stupid!

The most significant reason for this massive gap between the institutional power of the military and the lack thereof among the civilian parts of the state is money. Pakistan’s military expenditure as a percentage of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is highest in South Asia.

The military budget has also increased by 73 per cent between 2009 and 2018 and by 11 per cent between 2017 and 2019, according to a report prepared by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

On the other hand, in Punjab, the largest province in the country, the percentage share of education in overall provincial budget has decreased from 24 per cent in 2014-15 to 19 per cent in 2018-19. In Sindh and Balochistan, it has gone down from 21 per cent to 18 per cent in the same period.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 12 August 2020, on its old website.

Published on 4 Oct 2021