Before Hanju Kolhi got married in February 2017, no one asked her if she agreed to it. She did not even know the name of her future husband.

She belongs to a scheduled caste Hindu community and lives in Bhoro Kolhi village, eight kilometres west of Badin, where her parents work as peasants for a local landowner. She was married to a boy named Raju (who is a resident of Valo Kolhi village in Tandobago tehsil of Badin district) from her own caste but the couple started fighting within a few months of their marriage.

Hanju says her husband’s attitude towards her changed suddenly and he started quarrelling with her over minor issues. “The situation soon became so bad that he would often tie me in the sun and hit me with a slingshot,” she says. “I was also locked up in a room for two days, kept hungry, stripped naked and then beaten up.”

She continued enduring all this violence, Hanju says, but when her husband said in front of everyone, including her parents, that she had a wayward character, “I felt very bad and told him to kill me but not to make such an accusation.” Her husband became so angry at this that he left her at her parents’ home in July 2017.

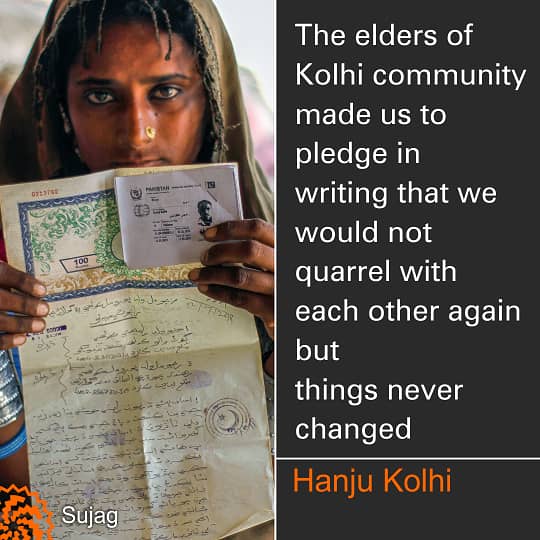

But, at the request of Hanju’s parents, the elders of Kolhi community reconciled the couple. The two were made to pledge in writing, in the presence of witnesses, that they would not quarrel with each other again. After the reconciliation, Hanju went to her husband’s home.

Her life, however, did not change and the fights and beatings continued as before. Consequently, Raju left her at her parents’ home again in December 2017 which made the elders of their community to intervene once again and reconcile them. Thus Hanju got back in Raju’s home once more.

A few days before thadri (a Hindu festival) last year, Raju left her at Bhoro Kolhi pretending that he had brought her there so that she could see her parts. He never returned to take her back even though the elders of the community made many efforts to make that possible. Hanju’s parents, however, cannot afford to keep their married daughter with them. They are already mired in debt and have eight more daughters to marry.

So, with help from some local officials of the Sindh Progressive Party, her father filed a petition a few months ago at Badin District Court, pleading that Raju be made to pay maintenance money and medical expenses of Hanju. His lawyer Manzoor Bilali says that he has filed the petition under the Muslim family law enacted in 1964 because, as he puts it, local lawyers and courts often rely on this law in such cases.

As his remarks suggest, most courts at district and tehsil levels in Sindh are still not using Hindu marriage laws passed in 2016 both by the National Assembly and the Sindh Assembly. These two laws provide for the registration of marriages among Hindu couples and also include mechanisms for the resolution of disputes over divorce and alimony.

Bilali says the reason why these laws are not used is that most lawyers in small cities like Badin have not even read them. The same is true of pundits who officiate at Hindu marriages. Instead of registering the marriages of Hindu couples under these laws, they deem it sufficient to solemnize their union under traditional religious rites.

Hanju's marriage was also solemnized by a pandit named Parsu Maharaj in the same traditional Hindu way that has been going on for centuries. The marriage was neither registered nor did it abide by other legal requirements as given in the recently promulgated Hindu marriage laws.

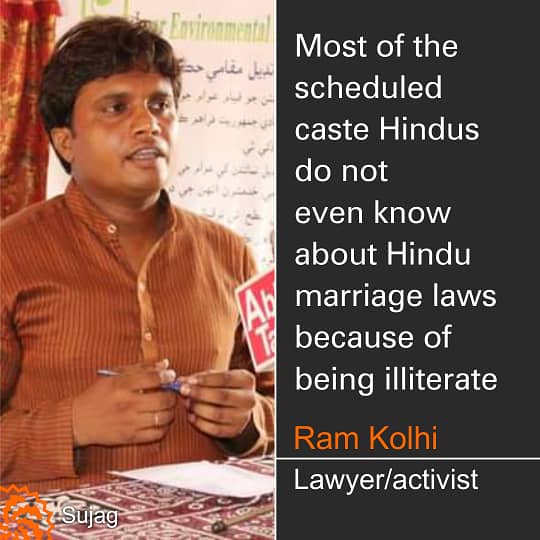

The majority of Sindh’s Hindu population, indeed, is unaware of the existence of these laws, says Badin-based lawyer and social activist Ram Kolhi. Some upper caste Hindus might be aware of them but most of the scheduled caste Hindus do not even know about them because of being illiterate, he says.

According to Ram Kolhi, the high prevalence of poverty among scheduled caste Hindus is also impeding the awareness and application of these laws. Lawyers and judges do not want to invest their time in learning about them because they believe that most of the cases under them will involve the members of scheduled caste communities who often do not have money to pay legal fees and other litigation costs.

Prisoners of customs

Choon Kolhi, a social worker based in Badin, keeps a close watch at the problems face by Kolhi community in his area. He point to a common behavior that prevents women from publicizing their domestic problems regardless of the price they have to pay for their silence. Under this social norm, he says, if a Kolhi woman goes to a court of law, she is deemed to have tarnished the honor of her family. “No one then wants to have anything to do with such a family.”

This, he says, explains why it took Hanju more than three years to go to a court against her husband.

Now that Hanju has knocked at the door of law, says Choon Kolhi, she must have also realized that she will never be able to get married again. So, he points out, she will either have to go back to her husband's house no matter what the circumstances or she may have to face insults all her life for not being able to live with him.

Just like her, many women belonging to about 14 villages of Kolhi community, including Bhoro Kolhi, are living quietly with their parents after leaving their abusive husbands. Every now and then, however, one of them gets so fed up with her life that she commits suicide.

Statistics collected from local residents show that six women committed suicide in these villages in 2020 alone. Four of them were living with their parents or brothers, having left their husbands.

Hanju's 62-year-old mother Sony fears that her daughter might also take her own life. “I am always scared that my Hanju, too, might take the same wrong path of committing suicide that a girl named Radha took in the neighboring village last year,” she says in a tearful voice.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 19th June 2021, on its old website.

Published on 18 Feb 2022