The government observed 18th December 2020 as the Farmers’ Day in order to acknowledge the role of farmers in national economy.

‘Salaam Kisan’ was top trend on social media that day. The events held in the name of farmers in many major cities were also well covered by news channels. At these events, Prime Minister Imran Khan and several of his ministers and advisors made loud claims and promises to the farmers to ensure a better price for their produce.

Around the same time, farmers in Sindh were staging a series of protests against what they called an unfair price for their tomato crop.

Starting from 15th December and continuing till 30th of that month, they staged protests in several towns and cities across the province. They also observed a hunger strike on 29th-30th December in front of the Hyderabad Press Club. In these protests, they demanded that the federal ministry of food security should withdraw its permission to import tomatoes from Iran because local tomatoes were being sold for nothing as a result of that import.

No national news media outlet covered these protest and no minister or adviser listened to the demands of protesting farmers.

Organizations leading the protests say the federal government initially allowed the imports only for a month in order to curb rising tomato prices in Pakistani markets but the permission was later extended for another three months. They say the extension has had a detrimental effect on local agriculture.

Highlighting this effect, Sindh’s provincial government wrote a letter to the federal government on 14th January 2021, asking it to stop importing tomatoes because their price in local market had crashed to such an extent that farmers were finding it impossible to meet their production costs. The letter also stated that Sindh’s 2020 tomato crop was sown on around 74,131 acres which was 18,300 acres more than the land under tomato cultivation in the previous year. Tomatoes’ yield per acre, the letter said, was also better this year than what it was last year.

For both these reasons, the extension in imports from Iran was unnecessary, says Fayyaz Hussain Shah Rashdi, president of the Sindh Aabadgar Board. An additional reason for stopping the import, according to him, was that tomatoes cultivated in Sindh had started arriving in markets by mid-December 2020.

He attributes increase in tomato prices in last October and November to monsoon rains in Sindh which delayed the transfer of tomato plants from nurseries to fields. Due to this delay, he says, the crop took longer than before to mature and, thus, tomatoes being grown in Badin and Thatta districts could not reach the markets in those two months.

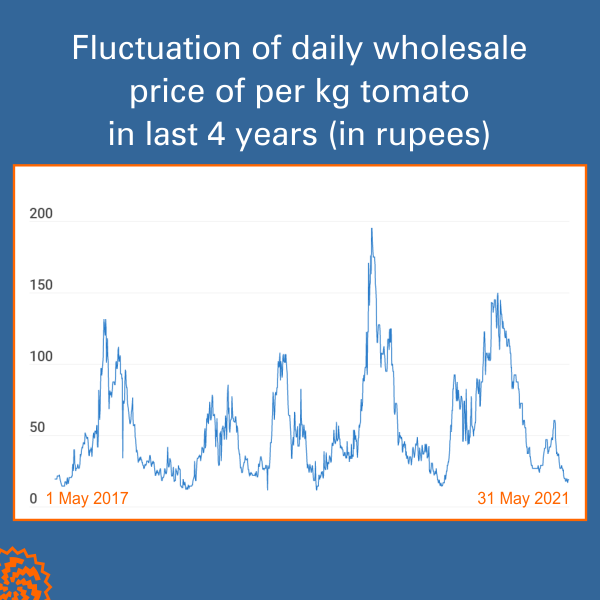

Official price statistics seem to follow these developments. In late October and early November in 2020, according to these statistics, tomatoes were being sold at 120 rupees to 150 rupees per kilogram in Lahore’s wholesale market. Their price at vegetable shops reached 400 rupees per kilogram during this period. But the wholesale price of tomatoes dropped in the last two weeks of December and was recorded at 70 rupees to 90 rupees per kilogram. A month later, however, this price dropped further to 25 rupees to 30 rupees per kilogram.

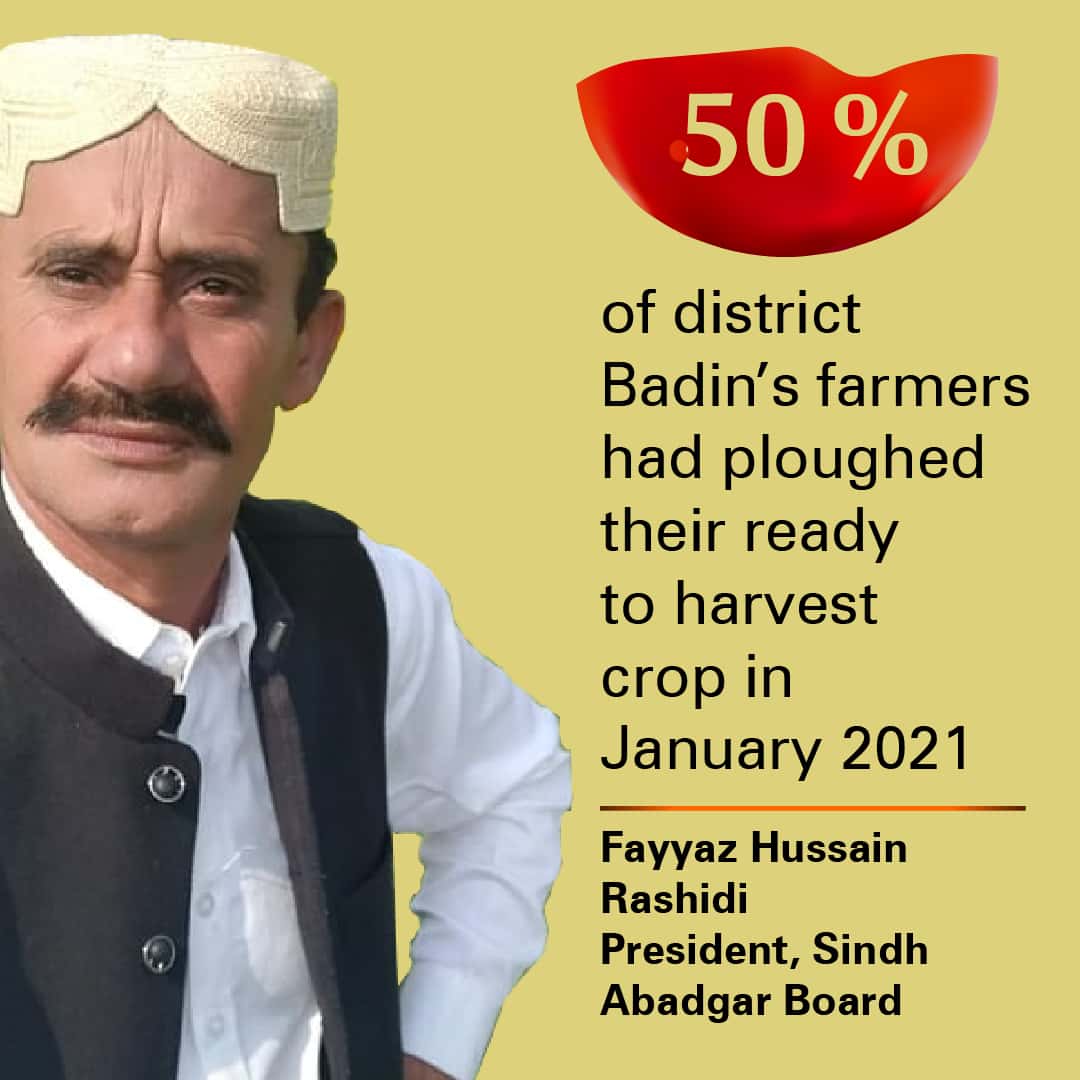

While the price was tumbling, news reported started emerging from Sindh that tomato growers there were destroying their crop. In Badin district alone, says Rashdi, 50 percent of tomato growers destroyed their crop in January 2021. He himself destroyed his nine acres of tomatoes in Badin’s Tando Bago taluka on 20th January – just as his plants were laden with tomatoes.

Shakeel Ahmad Kabor, another farmer from Badin, also ploughed his two acres of tomatoes with a tractor. “This time round my crop matured when the price of a 12-kilogram bag of tomatoes in Badin’s market stood at only 25 rupees,” he says. Consequently, according to him, plucking tomatoes from plants and taking those to market had become a loss-making affair. “I had only two options -- either to take tomatoes to market at my own expense or to plough the crop and thus use it as a natural fertilizer,” he says.

A national market for a provincial crop

The area under tomato cultivation in Sindh has increased by 600 percent in the last 20 years. In 2001-02, tomatoes were planted on only 14,332 acres in the province but this increased to 74,131 acres in 2020. Sindh, thus, had the largest area under tomato cultivation last year. Before 2011-12, it was at the third position after Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan.

Sindh currently also accounts for 35 percent of the total tomato production in Pakistan – representing the highest provincial share in the crop. In comparison, Balochistan contributes 25 percent of the crop and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab respectively produce 22 percent and 18 percent of Pakistan’s total tomatoes.

Tomatoes grown in Sindh are usually available in markets across Pakistan between October and May. Their supply has almost come to an end these days as Punjab’s crop has started reaching markets over the last several weeks. These tomatoes will be available till July when a new crop will mature in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. This crop will meet the demands of consumers across the country for the next three months.

“There is an excess of tomatoes in the markets as of now,” says Muhammad Jahangir Ali, a middleman at a wholesale market in Lahore’s Badaami Bagh area. “So, they are being sold at a very low prices”.

The price of good quality tomatoes in the wholesale market, according to him, stands at 15 rupees per kilogram. Relatively low quality tomatoes are selling for even less: 8 to 10 rupees per kilogram.

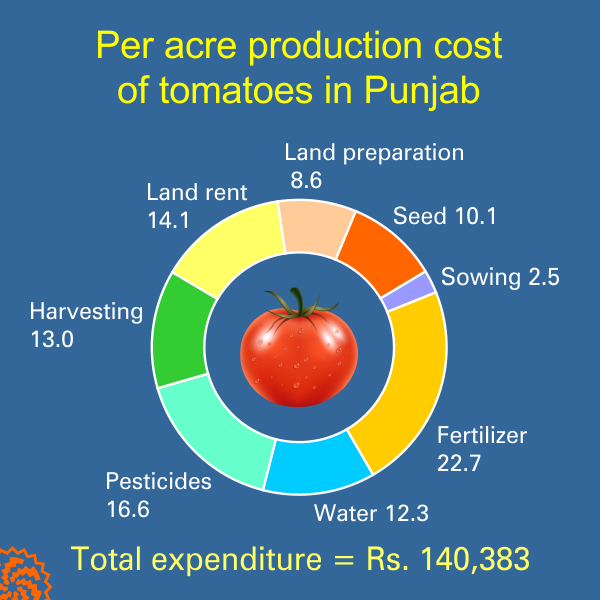

This price is so low that farmers can be seen on social media destroying their crops in various ways because they think that taking tomatoes to market will only increase their losses. Punjab government’s data -- showing that the cost of growing one kilogram of tomatoes is 16 rupees -- backs their calculations.

A research paper written in 2017 puts the cost of producing of the same amount of tomatoes at 24 rupees. This is just the cost of growing the crop. It does not include the cost of picking and packing tomatoes, the money needed to transport them from the field to the market and the middleman’s commission.

So, even if Punjab government’s cost estimate is taken to be correct, it costs 320 rupees to produce 20 kilogram of tomatoes. Workers who pick 20 kilogram of tomatoes and put them in a bag charge 20 rupees, says Latifullah, a small-scale farmer in Kamar Musani town in Punjab's Mianwali district. Packaging material costs 30 rupees and an additional eight rupees are required to take every bag to the market on a rickshaw, he says. Workers at the market charge seven rupees per bag to download tomatoes and the middleman receives 10 rupees per bag as his commission, he adds.

This means that a 20 kilogram bag of tomatoes costs -- from its sowing to its sale -- 395 rupees to a farmer. But, as Latifullah says, this year he was able to sell a 20 kilogram bag of tomatoes for only 100 rupees. He, therefore, had to bear a loss of 295 rupees on every 20 kilograms of tomatoes he has produced.

He is so heartbroken by this loss that he has decided not to grow tomatoes next year. He also complains that the government, Instead of paying attention to the plight of farmers like him, is celebrating the reduction in tomato prices as a success of its economic policies. He is also unhappy with the news media because, instead of raising a voice in the favor of farmers, it is only showing how happy urban consumers are at the reduction in tomato prices.

Tomato prices: a rollercoaster ride

Per capita consumption of tomatoes in Pakistan is increasing rapidly. In 2001, every Pakistani consumed 1.86 kilograms of tomatoes in a calendar year but, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), this amount increased to 4.8 kilogram in 2013. It has increased even further over the last seven years.

Tomato production in Pakistan has also gradually increased. In recent times, about 569,000 metric tons of tomatoes have been produced in the country every year.

Statistics also show that Pakistan experiences sharp decline in tomato prices once every three years. According to Agriculture Marketing Information Service, a government agency based in Lahore, the same thing happened in 2016-17. In the first half of that year (from September 2016 to March 2017), the price of tomatoes did not fall below 50 rupees per kilogram but then it fell to 10 rupees per kilogram in April, May and June. This decline was due to the fact that tomatoes were planted on 145,542 acres in 2016 – largest area under tomato cultivation in Pakistan’s history until then. Consequently, tomato production soared and its price plummeted.

But then the area under tomato cultivation started to decrease starting in 2017. In 2019, it was reduced to 136,545 acres due to which the price of tomatoes increased significantly by the end of 2019 and early 2020.

Seeing this, farmers once again increased the area under tomato cultivation in 2020. So, the price fell again.

Mir Zafarullah Talpur, a progressive farmer from Mirpurkhas district in Sindh and a member of the Sindh Aabadgar Board, also links price fluctuations with the area under tomato cultivation. He says heavy rains started after farmers had sown their tomato crop in the summer of 2019. These rains, according to him, damaged tomato crop on thousands of acres in Thatta, Badin, Tando Muhammad Khan, Umerkot, Matiari, Mirpurkhas and Larkana districts. Consequently, he says, the supply of tomatoes fell short of their demand and their price reached 400 rupees per kilogram. “Next year, in 2020, farmers in Sindh planted more tomatoes, hoping that they will get a good price like they had done in 2019 but now there are no buyers for their produce.”

Talpur says Pakistan will have to face the consequences of this situation next year when the area under tomato cultivation will decrease again -- and the price will go up sharply.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 11 Jun 2021, on its old website.

Published on 26 May 2022