Angry young men roam the paths leading to their villages. They carry sticks and stop every stranger travelling on those paths. If the traveler is found to be a government official, visiting their area in order to carry out a survey for the construction of a dam, they do not allow him or her to perform that task.

These youngsters belong to seven villages located along Ling Nullah, a rainwater stream that starts from Rawalpindi district’s mountainous eastern tehsil Kahuta and runs through a valley near the town of Rawat located about 19 kilometers to the southeast of Rawalpindi’s city center. The provincial government of Punjab has recently revived a decade-old plan to construct a dam on the lands belonging to these villages. It has already imposed Section 4 of the Land Acquisition Act in three tehsils of Rawalpindi district to authorize itself to obtain 18,566 kanals of land for the dam’s construction.

“Around 1000 families will be affected by the dam,” says Imran Kiyani, a resident of Barwala, a picturesque village along the stream. “Once they are displaced from here, they will have nowhere else to go,” he says.

His own village houses 250 families who will all be displaced if the construction of the dam – officially known as Daduchha Dam because of its proximity to its eponymous village – goes ahead as per the government plans.

A source in the office of Rawalpindi’s deputy commissioner tells Sujag that the government views Daduchha Dam as being absolutely essential for supplying water to Rawalpindi district where groundwater level is going down very rapidly. “The dam will provide water for both domestic consumption and for agriculture,” he says.

It was, indeed, the Supreme Court of Pakistan that had taken up suo-moto hearings in 2018 for the construction of Daduchha Dam after knowing about water scarcity in Rawalpindi. At one stage during those hearings, Malik Riaz Hussain, who heads Pakistan’s largest real estate development company, Bahria Town, promised that he could build the dam with his own money provided the government’s bureaucracy did not interfere in its construction. Later, however, the Punjab government assured the court that it could build the dam on its own within two years.

Those two years have already passed but the construction has not started yet.

In October 2020, however, the provincial government awarded the construction contact to the Frontier Works Organization (FWO), the engineering wing of the Pakistan Army. FWO is expected to complete the dam in three years at an estimated cost of six billion rupees (excluding the cost of acquiring land which amounts to another six billion rupees).

The contractor has set up its site office not very far Barwala village and the district administration claims to have already acquired 1640 kanals of land in the area to start the project.

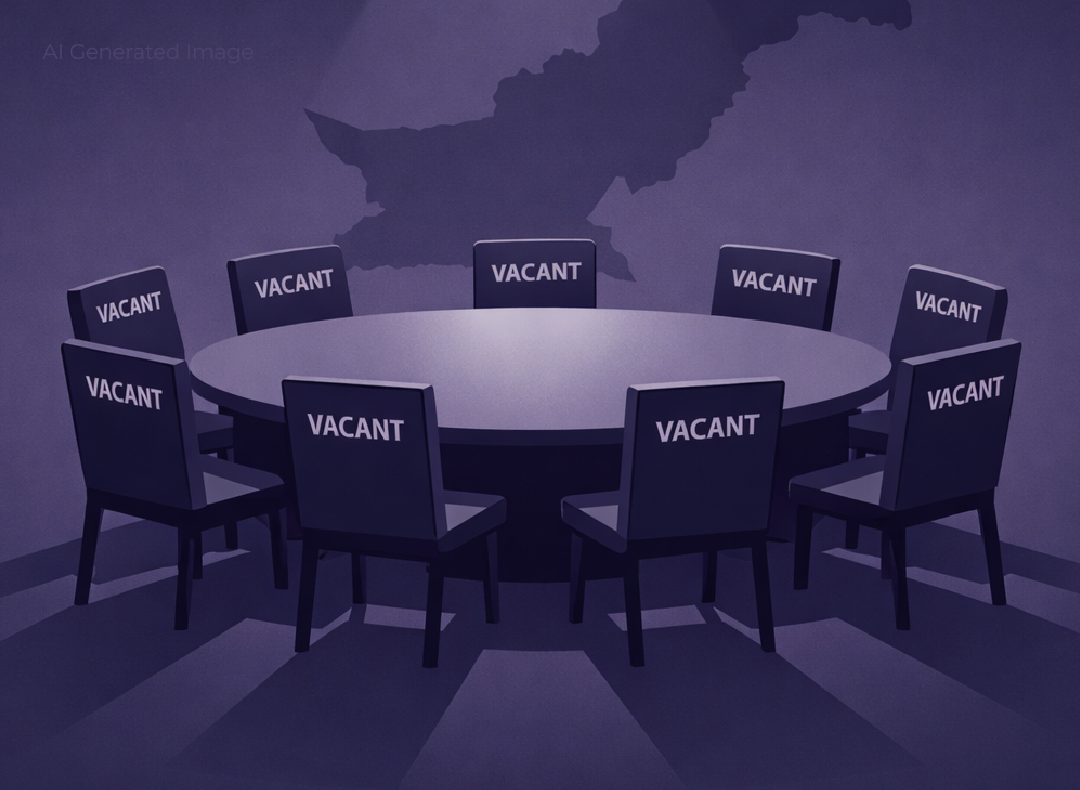

The villagers, on the other hand, are not sure how much land the dam will occupy and where exactly will it be located. They says they have had several meetings with the district administration but still do not know the answers to these questions. “The district administration itself is not clear about the size of the dam’s reservoir,” says Ajmal Kiyani, another resident of Barawala.

News reports suggest the maximum storage capacity of the dam will be 60,000 acre feet. Even when it reaches its dead level – that is, the point where water cannot be drawn from it – it will still have 15,000 acre feet of water in it.

The villagers, though, are clear that they will not let the construction start until their voices are heard.

“The elders of the villages to be affected by the dam met last week. There were about 1000 people in that meeting. They all then marched towards the FWO site office and forced FWO to stop its work,” says Imran Kiyani.

The meeting also made Rawalpindi’s assistant commissioner to visit the area. He informed the local residents about FWO’s apprehension that it could lose the contract if it did not initiate the construction of the dam immediately. He, therefore, “begged us to allow FWO to resume work,” says Imran Kiyani. “The assistant commissioner also assured us that our demands will be met within a week’s time,” he adds.

Only one more day is left before this deadline expires. “If our demands are not met,” says Imran Kiyani, “we will march to the FWO site office again.”

One land, two prices

Defense Housing Authority (DHA), the military-run agency that owns vast housing projects in several parts of Pakistan, including Rawalpindi, acquired 18000 kanals of land in Barwala, Daduchha and their adjoining villages in the 2000s to build a project called DHA Valley. Later, the Lahore High Court declared this acquisition as null and void but, according to Ajmal Kiyani, a resident of Barwala, DHA is still occupying that land.

The local residents claim the original site of the dam included the land under DHA’s purported occupation. They allege that DHA has pressurized the Punjab government to change the site of the dam.

An official working with Rawalpindi’s deputy commissioner dismisses these allegations and says the Punjab government has always been committed to constructing the dam near Daduchha village. “We have resisted all the pressure to change the site of the dam,” he claims.

Hameed Kiyani, a school teacher living in Barwala, has another worry. “We are ready to accept the construction of the dam in the national interest but we fear that it will be used as a precursor to the development of luxurious housing schemes for army officers,” he adds.

In order to alleviate these worries, he suggests the government should use DHA Valley’s land to resettle the villagers to be displaced by the dam. “You want to construct dam? Okay, fine, go ahead but give us the land that DHA illegally acquired,” he says.

Yet another complaint the villagers have is about the price of land being acquired from them. “The compensation of 90000 rupees for a kanal of land will not buy us a house one-fourth that size in Rawalpinid city,” says Jamsheed Kiyani, an elder of Barwala village.

His village fellow Imran Kiyani says he spent millions of rupees on the construction of his house eight years ago – as have most other people living in the village in recent times – but the money being offered by the government is only a fraction of that.

Samina Kiyani, working as a lady health worker in a dispensary in Barwala, also says the money she will receive after the acquisition of her land is a pittance. “One cannot rent a one-room house in Rawalpindi for six months with 90000 rupees,” she says.

She and other residents of Barwala demand the government pay them at least the present-day equivalent of 96000 rupees per kanal that DHA paid them more than a decade ago. Alternatively, they say, the government should price their land at the same rate as a plot of land of the same size in DHA Valley does. “Our village has all the facilities that DHA Valley has. It has water, it has electricity and it has gas. It also has schools. So, why can’t we get the same price for our land which a DHA plot is getting?” says Jamsheed Kiyani.

For most of the villagers – except for a tiny well-off minority -- their houses are also the only thing they have. They cannot afford to lose them without running the risk of becoming homeless forever.

Batool Kiyani, a widow and a mother of four young daughters -- one of them being disabled -- says the only solace in her life is that “I am living under my own roof”. She, however, fears the acquisition of her house for the dam will take that solace away from her. “I will have no place to go to. Where will I take my daughters?” she says.

Others worry about the loss of livestock grazing pastures and agriculture lands – the two main sources of livelihood in the area. “This is nothing less than our economic strangulation,” says Imran Kiyani.

The older one among them also fret about the prospect of leaving the graves of their fathers and forefathers behind. Raja Pervez — a village elder in Khanpur – is distraught over the prospect of having to leave his village. “I weep at night when I think about leaving this place,” he says.

The villagers, therefore, are ready to do whatever it takes to make themselves heard. “We will not leave this place. We are ready to die for it,” Raja Pervez warns.

The only other remedy they have is that the judiciary comes to their rescue as it did when it gave a verdict against the acquisition of land for DHA Valley.

So, the residents of both Daduchha and Barwala are hoping that they will get a sympathetic hearing on January 26, 2021 when proceedings take place at the Lahore High Court’s Rawalpindi bench on their petitions – as well as 12 other petitions. They are optimistic that the court will provide justice to them.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 21 Jan 2021, on its old website.

Published on 10 Jun 2022