Three wells do exist in Khajurari village but none of them contains water.

The last of these wells was built by the locals around 2010. The chief of the local Nohri tribe, Ghulam Haider Nohri, says it provided water a few years but then it went dry -- just like the first two wells.

Khajurari is a remote village in Diplo tehsil of Sindh’s south-eastern desert district of Tharparkar. It is inhabited by people belonging to the scheduled caste Hindu communities — Kolhi and Bheel — and a Muslim community called Nohri.

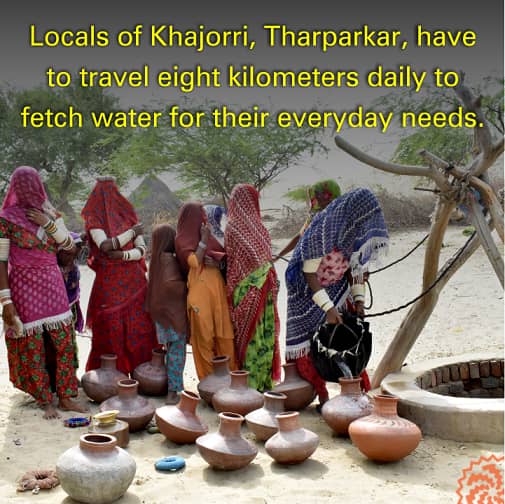

Lying 45 kilometers from Diplo towards the Pakistan-India border, the village — consisting of approximately 200 households — does not have any civic amenities such as electricity and paved roads. The locals have to travel eight kilometers every day to another village to fetch water for their daily needs. Some of them travel on donkeys while others make this journey on foot. The villagers, Nohri says, have no other option but to endure this hardship because they “don’t have the money to dig a new well in their village”.

Same is the situation in hundreds of villages across Tharparkar which has a total population of over 1.6 million.

As per local legends, a large river once flowed through this area but it dried up thousands of years ago. Now, sand dunes can be seen everywhere in Tharparker with human settlements, pastures and agricultural lands nestled in between them. All these are entirely dependent on rainfall and groundwater.

In terms of annual rainfall, Tharparkar is one of the driest parts of Pakistan. It receives an average of about 11 inches rain a year. In comparison, average rainfall in the central plains of Punjab province is about 25 inches per year.

To store rainwater, the residents of this district use a number of traditional methods. The most important of them is maintaining natural ponds, locally known as Tarai. These ponds have water only in the months of July, August and September, as this district receives 80 per cent of its rainfall in these three months. The rest of the year, they remain covered with sand.

So far as groundwater is concerned, its level in Tharparkar district is running very low. Usually, one has to dig up to 400 feet to extract drinking water. This problem is more prevalent in Chachro tehsil which abuts Indian border. That is why local women in this part of Tharparkar are often seen roaming in search of water with clay pots balanced on their heads.

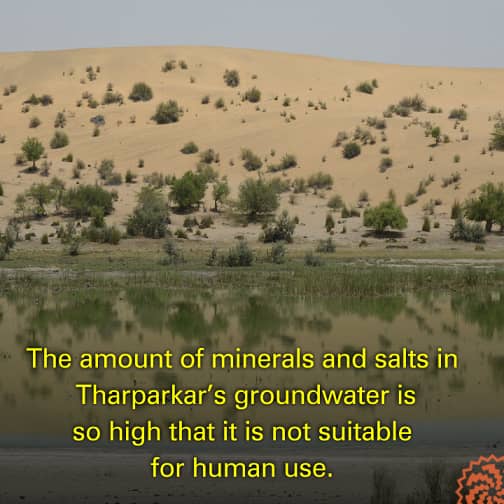

Groundwater in Tharparkar is also so replete with salts and minerals that it is not suitable for human health, says Ata Muhammad Rind, a local geologist. The amount of these elements in this water is 10,000 to 20,000 milligrams per liter, which is many times higher than the acceptable standard set by the World Health Organization: 300 milligrams per liter.

The locals, however, are compelled to drink this water because, according to Rind, they do not have any other option. The usage of this unhealthy water, though, causes large scale stomach and teeth diseases among the residents of this area.

Poorly-planned water supply schemes

The amount of money invested in water supply schemes in Tharparkar could easily outmatch the money spent in any other rural district in Pakistan for the same purpose.

Especially, in the last two decades various government agencies and non-governmental organizations have launched a number of projects here with the sole purpose of providing clean drinking water. Wells have been dug in dozens of villages and hand or machine-operated pumps have also been installed in many areas. But only a few of these projects have worked. The rest have stopped working due to financial and technical problems.

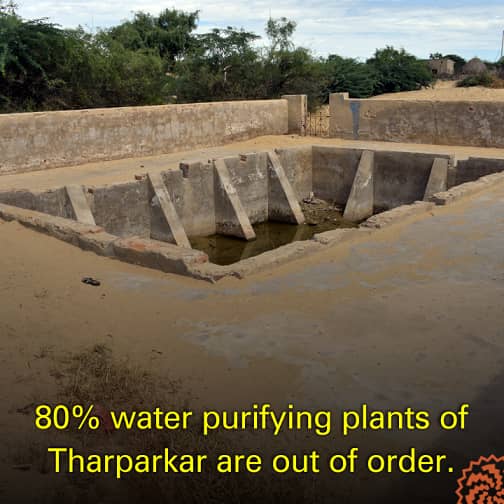

Similarly, reverse osmosis plants have been installed in many villages to purify groundwater through modern scientific technology. The largest project for their installation has been planned and funded by the Sindh government. This project, worth 33 million US dollars, began in 2015 with the installation of a plant in Mitthi, the district headquarters of Tharparkar, with a capacity of supplying eight million liters of clean water per day.

It, however, worked only a short while.

The other major problem with the project is that the provincial government could set up only 400 of the proposed 750 plants over the last six years. The machinery for the rest of them, according to a Mitthi resident Kamal Dev, either did not reach their proposed installation sites or was misappropriated upon arrival.

Dev also alleges that the sites for the most of the plants were selected by the relatives and friends of government officials. This, he says, shows how the government did not even carry out a feasibility study for such a large project so as to find out which sites were suitable for the plants and which ones were not.

“Sub-standard material was also used in the installation of plants which has caused 80 per cent of them to fall into disrepair,” he says.

The provincial government officials, on the other hand, say they have no role in installing the plants and that this responsibility lies with a private company called Pak Oasis.

An official of the company admits that the plants in Tharparkar were set up by Pak Oasis. “But it is the responsibility of the provincial government to keep them running and take care of them,” he says declining to be named. According to him, the main reason for the breakdown of the plants is the deployment of untrained operators.

Some plants that are still in working condition have also been shut down for the past several months because the Sindh government is not paying their operators regularly.

Tall claims

Canal water has been available for decades for agricultural and domestic use in Badin, Umerkot and Mirpur Khas districts which are located next to Tharparkar. It was delivered to Tharparkar for the first time only about 15 years ago during General Pervez Musharraf’s regime.

Under this government-funded project, canal water from the town of Naukot in Mirpur Khas district was channeled through a 150-kilometer pipeline to the towns of Kaloi and Diplo via Mitthi so that it could be used for domestic purposes in these settlements.

After a flood in 2010 destroyed the pipeline between Kaloi and Diplo, that portion was never restored. After the flood, however, water supply in the pipeline connecting Naukot and Mitthi was also reduced to one day – from one week -- every month.

It was around that time that the process of mining and using coal to generate electricity began in Tharparkar. This required a large amount of water on a daily basis. As a result, the pipeline was extended from Mitthi to the town of Islamkot, 42 kilometers to the south, and all its water was allocated to power generation.

Residents of Tharparkar complain that if canal water can be supplied to cool down the machinery of power plants on a daily basis then why the same cannot be done to meet the needs of the local population. "We have been clamoring for generations for the provision of water but no government has ever listened to us. Coal projects, on the other hand, are being provided with as much canal water as they need,” complains Chandar Meghwar, a resident of Bhurilo village.

Due to these complaints by the people of Tharparkar, water expert and environmental scientist Pervez Amir believes that the government will not be able to reap the economic benefits of generating electricity from local coal without first resolving the district’s water-related issues. Unless all natural resources, including water, are distributed equitably among local residents, they will continue to view all government projects related to coal with suspicion, he contends.

Ashfaq Memon, Sindh Chief Minister’s Advisor on Canal Water and Irrigation Improvement, says the supply of canal water to power plants through the Naukot-Islamkot pipeline is a temporary arrangement which would end soon. The Sindh government, he asserts, has completed 80 per cent of work on a canal project to carry water from Makhi Farsh area in Umerkot district to Nabisar near Mitthi and then channel it to Vijehar village of Islamkot tehsil to meet the water needs of power plants.

He is hopeful that, after the completion of this project, water from Naukot-Islamkot pipeline will be available to the residents of Mitthi, Islamkot and their surrounding villages.

But local residents are not sure that this will ever happen. They fear that the water brought to Tharparkar through both dthe canal and the pipeline will be dedicated to power plants. Some of them, in fact, complain that these very plants are also responsible for lowering groundwater level as they have been allowed to use that water without any restrictions. They allege that local water resources are becoming scarcer owing to this reckless use of groundwater.

As a result, water wells in many villages around the coal mines have either run out of water or their water level has gone down drastically over the last five years. This problem is especially acute in villages like Bhave Jo Tar, Khario Ghulam Shah and Varwai.

Naseer Kumbhar, a local journalist and researcher, pointed out one such village, Vikrio, while talking to Third Pool magazine last year. Water from a newly dug 300-feet deep well in the village disappeared some time ago due to which about 3,000 local residents had to go to different nearby places for months to fetch water for their daily needs, he said.

Now he fears that the problem will intensify in the coming months and years. He, therefore, asks the government to “immediately conduct a study in order to devise a mechanism for the restoration of the fast-depleting groundwater resources in Tharparkar”.

Published on 30 Sep 2021