Ram Ji, a 50-year-old resident of Tharparkar’s tehsil Diplo, works as a labourer on the salt lakes (locally known as ‘sann’). His home is about 20 kilometres away in the village of Mehtar Dhanani, where his three young daughters and one son accompany him to assist in the work.

Rami Ji pulls a trolley loaded with salt extracted from the Ram Ji Lake, dumps it on the lakeside for drying, and then prepares for the second round. During this process, their four children continuously fill bags with dried salt.

Ram Ji explains that no other employment opportunities are available near their village, so they are compelled to come here. However, the wages are so low that the entire family has to work all day, yet making ends meet is not easy.

He says that after washing the salt, they experience itching all over their bodies in the evening, making life miserable. There are no protective clothing or medical facilities here. They rely on the mercy of the salt mine owners. In case of injuries, they buy ointments from the city.

The Tharparkar district is renowned for its five minerals: coal, China clay, salt (lake salt), granite, and laterite (red stone). Tharparkar is the only district in Sindh that produces China clay and granite.

The Sindh Bureau of Statistics released a survey report in October 2022, according to which Tharparkar emerged as the leading district in Sindh for mineral production during 2020-21. In that year, the district extracted minerals worth a total value of PKR 1 billion 38 crore and 98 lakhs rupees.

Tharparkar is the largest coal producer, accounting for 74 per cent of the total coal production in the province, and it contributes 98 per cent of the total salt production. Around the region of Karoonjhar’s hills is a long chain of salt lakes, locally referred to as ‘kans’ or ‘sann’ in Sindhi.

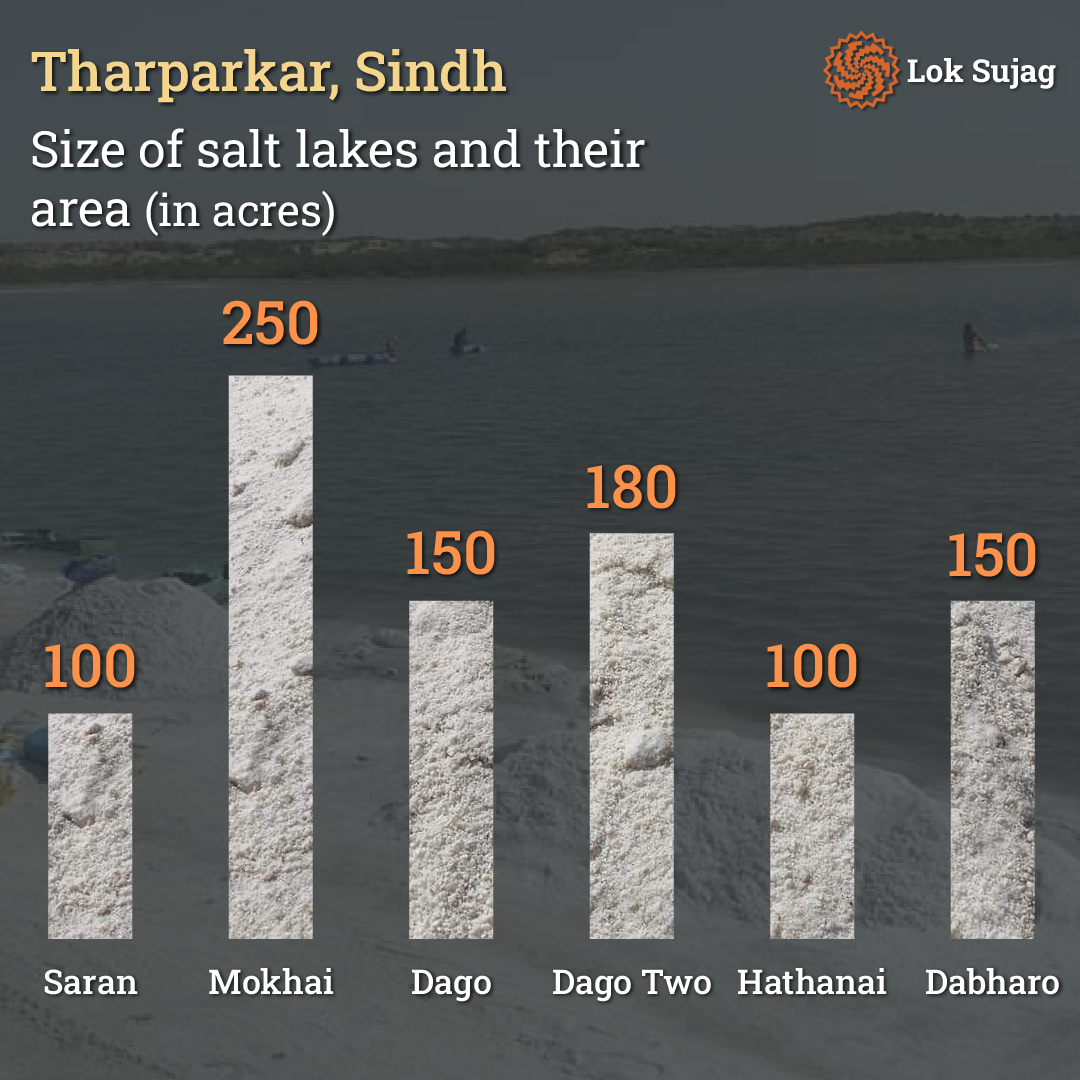

Sarun is considered the largest lake in Tharparkar, located 20 kilometres West of the Tehsil Headquarters Diplo. It covers 100 acres of land. The process of collecting salt from the Sarun Lake and the adjacent lakes began five years ago and then continued spreading.

Apart from Saran, other large salt lakes in Thar include Mokhai Lake, 250 acres; Dagu, 150; Dagu Two, 180; Hathani Lake, 100 acres; and Dabhru Lake, 150 acres.

“Some salt processing (cleaning and packaging, etc.) is carried out in nearby factories. Around 500 tons of processed salt from Tharparkar is sent to the domestic market, while the remaining raw salt is either exported or sent to Karachi for processing.

In the fiscal year 2020-21, 2,22,335 metric tons of salt were extracted from Tharparkar. This salt is primarily used in various industries, such as textiles and leather factories. Moreover, significant quantities of this industrial salt are also exported, contributing to foreign exchange.

During the monsoon season, water from the Karoonjhar hills is responsible for bringing the brine to these salt lakes, or sometimes, when water accumulates underground, it surfaces as brine. After three to four months, when the water in the lakes becomes scarce or dries up, a layer of salt, four to five inches thick, solidifies.

The upper layer of salt is harvested, and within a few days, a new layer forms. This process continues for about eight months.

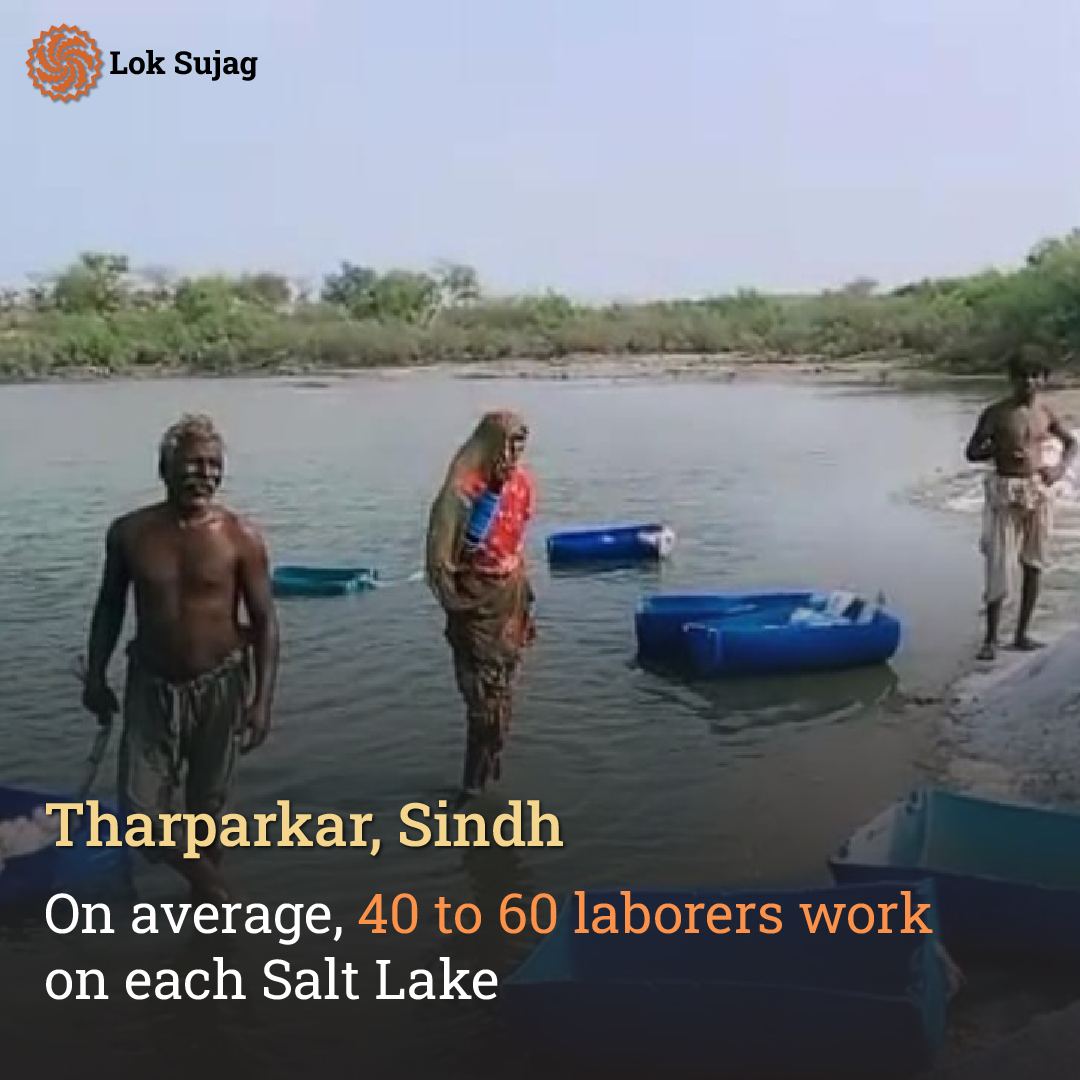

The Mines Department of Tharparkar annually awards 71 lake salt extraction contracts. Most of the salt is extracted by labourers who fill bags. They have to stand in knee-deep water and salt for hours daily. On average, about 40 to 60 labourers work on each lake.

Dr Zulfiqar Nehri, a dermatologist, says that those working with salt often suffer from allergies and itching on their skin. These skin problems can be severe and may even lead to high fever. Therefore, labourers should wear long boots and gloves during work.

Ram Ji explains that hundreds of labourers work on Tharparkar’s salt lakes. However, none of them are registered with any government department. They receive no protective gear from the contractors, and if anyone asks for better conditions, they are dismissed from their jobs.

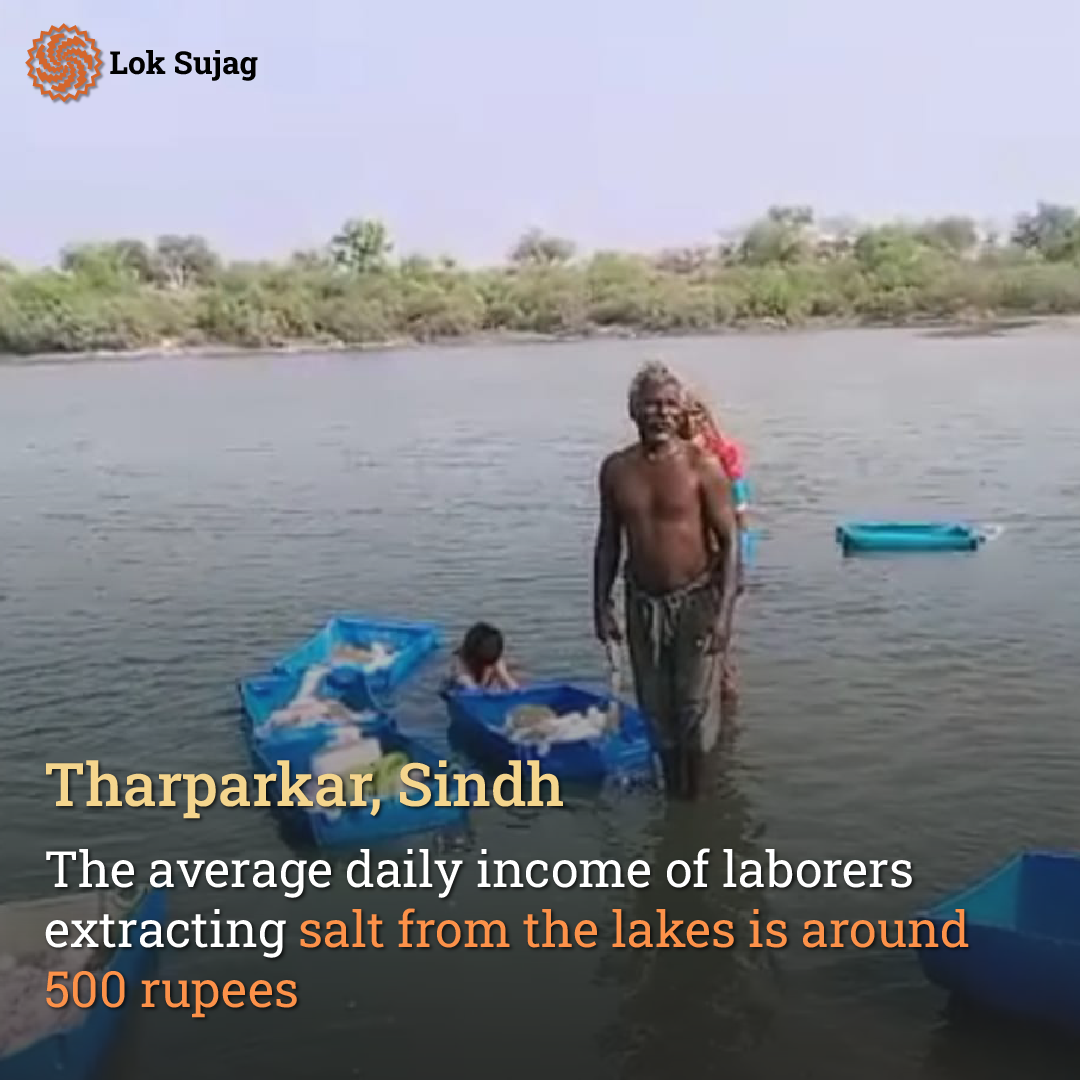

“One labourer is paid 16 rupees for bringing 60 kilograms of salt from the lake and 10 rupees for loading 40 kilograms of salt into the truck. A labourer can fill about 20 bags daily, so they don’t earn more than 500 rupees daily.”

Another labourer, who requested to remain anonymous, mentioned that payment was not received in cash but through a voucher. This voucher is collected after some time by the contractor’s clerk. Initially, payments were made within 15 days, but now it takes four to six months to receive the payment through the voucher.

“If a labourer wants to get cash on the same day, brokers or clerks give the cash in exchange for the voucher, but they deduct 400 rupees from a 1,000-rupee voucher. Most labourers must bring flour for their families in the evening, so they prefer taking 800 rupees as wages.”

Officials from the Labor Department, admitting their helplessness, say that labour laws are not effectively enforced in Thar and primarily due to influential contractors; the department has also distanced itself.

An officer from the Labor and Manpower Department, who wishes to remain anonymous, mentioned that the leaseholders of salt are responsible for the welfare of the labourers. According to the Sindh Mines Act of 1923 and the Sindh Concessions Rules of 2002, providing first-aid facilities to labourers is mandatory.

He says leaseholders must register labourers with the Employees Old-Age Benefits Institution (EOBI) and the Workers’ Welfare Board. According to the law, labourers should be provided with a written contract specifying their wages, but this is not happening here.

Sain Dad Hangor and the Sindh Mazdoor Tehreek (Sindh Labor Movement) have been raising their voice on this issue from their platform for several years. He argues that the capitalists have made life miserable for the labourers. Labourers are paid very little here, with no social security or safety.

The largest salt leaseholder in the area, Muhammad Sharif Dipalai Meman, claims that his family has been running the salt lease business for generations.

He claims that they fulfil all the government requirements for this work. There are no permanent employees here; everyone works on daily wages. Labourers face minimal risks in this job, and the Labor Department has no role here.

Also Read

Farmers in Tharparkar demand fair prices for local crops amidst rising seed costs and decreasing crop sales

Mohammad Sadiq Menghrio, the Deputy Director of the Mines and Minerals Department, explains that initially, the salt lease used to cost 150 rupees per acre annually. Still, now it has been raised to 2,000 rupees. There are indeed no facilities for labourers. The labour department oversees these matters, and in Tharparkar, the Labor Department does not operate.

Atta Muhammad Rind, an expert in land resources, has conducted extensive research on Tharparkar’s mineral resources for a long time. He states that the government receives an annual fee of 50 million rupees from the salt mines and factories in Tharparkar. However, local people do not benefit from this at all.

He suggests that the royalty and lease fees should go into the account of the Mines and Minerals department. This would bind the department to spend this money on local development. The salt labourers are leading miserable lives here, and it is essential to subject salt factories to the Industrial Act and labour laws.

Published on 16 Sep 2023