Christians in Pakistan are likely to join the chorus that is questioning the credibility of 2017 population census. Their longstanding complaint that their population is routinely under-reported in every demographic data has, indeed, been substantiated with the numerical evidence thrown up by this census.

This evidence is part of the census statistics released by the government a few days ago. It shows that the population of Muslims in Pakistan has grown from 127.4 million in 1998 to 200.4 million in 2017, exhibiting an overall growth of 57.2 per cent in 19 years. The non-Muslim population, on the other hand, has increased by 48.7 per cent during the same period.

Surprisingly, this entire difference of more than eight percentage points seems to have affected Christians alone. Their population has grown only by 26.3 percent between 1998 and 2017.

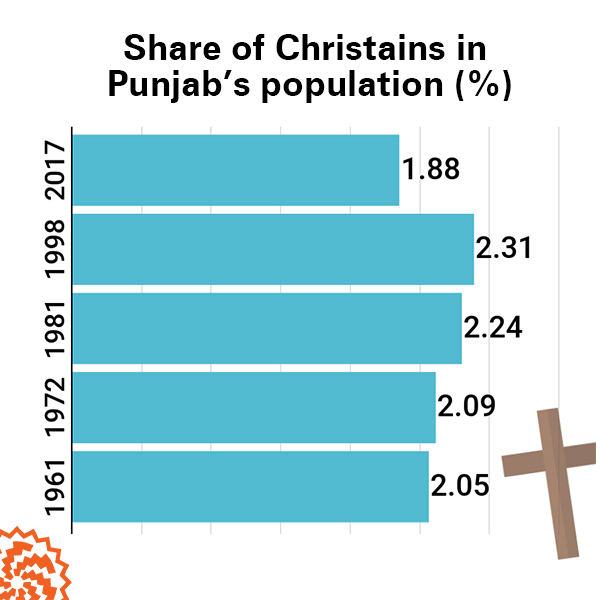

In Punjab, where a majority of Pakistani Christian lives, difference between the population growth of Muslims and that of Christians is, in fact, even higher. According to the census data, Muslim population in the province has grown by 50.3 percent between 1998 and 2017 but the growth of Christian population has been just 21.6 percent in the same period.

In yearly terms, Muslim population in Punjab has grown at an annual rate of 2.2 percent while that of Christians has risen by less than half that rate – 1.0 percent per annum. For the whole of Pakistan, annual growth rates for Muslims and Christians have been 2.4 and 1.2 respectively.

This difference is both staggering and unprecedented.

In earlier censuses, population growth rate of both Christians and Hindus actually exceeded that of Muslims. Given this trend, a sudden decrease in the growth rate of Christian population is hard to explain.

These numbers hide a stark reality: Had the Christian population increased at the same rate as the Muslim one did, 2017 census would have counted 650,000 more Christians than it actually did. In other words, one in every five Christians seems to have been missed out by the census. Not so surprisingly, 486,000 of these uncounted Christians would be living in Punjab.

Consequently, the share of Christians in Punjab’s population has dropped from 2.31 per cent in 1998 to 1.88 per cent in 2017.

This substantial under-counting is bound to aggravate the already deplorable socio-economic plight of Christians living in Pakistan. If nothing else, it is likely to affect their claims over state resources and their political significance.

They are also likely to be marginalized even within non-Muslim Pakistanis. Their very low population growth rate will allow the combined cohort of Caste Hindus and Scheduled Castes – which has registered a high growth rate – to supersede their electoral salience.

The numbers show this vividly: According to 2017 census, Christians constitute just 36.1 per cent of the total non-Muslim population of Pakistan while the combined Hindu cohort constitutes 60.8 per cent of all non-Muslims living in Pakistan.

This was different in 1998. Christians were then 42.5 per cent of the non-Muslim Pakistanis whereas the combined Hindu cohort was 49.7 per cent. Within this cohort, Caste Hindus were 42.9 per cent of the country’s total non-Muslim population – almost equal to Christians back then.

Caste versus religion

The other major non-Muslim group living in Pakistan – the combined cohort of Caste Hindus and Scheduled Castes – has experienced no downturn in its population. Its population growth rate has also continued to follow the historical trend – exceeding that of Muslims even in 2017 census.

It is important to highlight a distinction here. Caste Hindus and Scheduled Castes were categorized as two separate groups in all the censuses held in British India since 1882. This practice continued in the first three censuses held after the creation of Pakistan.

General Ziaul Haq, however, devised a new political system under which the followers of a religion could vote only for an election candidate belonging to their own religion. In accordance with this separate electorate system, seats in the national and provincial legislatures were divided among Muslims, Christians, Hindus and others proportionate to their share in the population.

Those belonging to Scheduled Castes were major losers under this system. Their distinction from Caste Hindus was ignored and they were merged in a larger category of ‘idol-worshippers’ who were given a combined representation in various elected forums. Inevitably, all the seats in these forums went to Caste Hindus who are more resourceful and more politically connected than those belonging to Scheduled Castes.

The census authorities followed this practice and clubbed the two communities together in 1981 census.

Separate electorates continued till 1997 elections. The census held in the next year restored the distinction between Caste Hindus and Scheduled Castes. In that census, however, only two of every 15 members of their combined cohort identified themselves as belonging to Scheduled Castes. All the rest categorized themselves as Hindus.

This marked a big change from 1961 and 1972 censuses in which 10 of every 15 members of the combined cohort had identified themselves as members of Scheduled Castes – with only five categorizing themselves as Hindus.

In 2017 census, Scheduled Castes, or Dalit, identity seems to have bounced back – albeit slowly. The latest census data shows that three out of every 15 people belonging to the combined cohort prefer to be identified as members of Scheduled Castes rather than being called as Hindu.

The data thus shows a far higher growth in the population of Scheduled Castes than that of Caste Hindus. Consequently, those belonging to Scheduled Castes now comprise 1.7 per cent of Sindh’s population. In 1998, they were only 1.0 per cent of the province’s total population.

Overall share of the combined Caste Hindu and Scheduled Caste cohort in the province’s population has also gone up owing to its higher population growth rate (or perhaps better counting). Together, Caste Hindus and the members of Scheduled Castes are now 8.7 percent of Sindh’s total population. In 1998, their combined share in the provincial population stood at 7.5 percent.

Controversies galore

The census data being released now is certain to aggravate many existing complaints of various demographic groups. Pakistani Christians, for instance, are highly likely to contest these figures; activists for the rights of Scheduled Castes are also likely to clamor that they are still being undercounted – particularly when compared to their numbers in 1961 and 1972.

Some other groups have already contested the census statistics. The provincial government of Sindh has been complaining since 2018 that the province’s population has been undercounted by around 20 million. Similarly, political parties belonging to Karachi, particularly Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), have been also saying that the city’s population is actually much higher than 16 million as shown by the census.

These complaints were among the main reasons why the census did not get an official approval in more than three years after its completion. Last month, the Council of Common Interests, the highest body empowered to resolve differences and disputes within the constituents of the federation, finally gave that approval (with Sindh still dissenting). Consequently, Pakistan Bureau of Statistics has started publishing select demographic datasets on its website.

Expect more controversies and more complaints as the number of datasets being released increases in coming weeks and months.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 14 Jan 2021, on its old website.

Published on 8 Jun 2022