The ruling Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) struck down a draft law on enforced disappearances presented in the National Assembly on 26th January, 2021. This is the second time in less than two years that PTI has opposed the passage of a law on the same subject. In both instances, the draft of the law was presented by Mohsin Dawar, a member of the National Assembly from North Waziristan tribal district.

When his first draft was rejected on 30th April, 2019, he said in a tweet that PTI had “exposed [itself] by opposing” the draft. This time, too, he did something similar. Appealing to Federal Minister for Human Rights, Shireen Mazari, to support his draft, he reminded PTI’s parliamentarians how some of them were once very vocal about enforced disappearances. His remonstrations fell on deaf ears.

This might suggest that the PTI government has never done anything on the issue. On the contrary, its federal ministry of human rights drafted a law more than two years ago with the intent to criminalize enforce disappearances. This draft, however, is gathering dust on some office table inside the federal secretariat.

The idea of passing such a law first originated in the Senate’s Functional Committee on Human Rights. The committee recommended in late 2018 that legislation was needed to recognize enforced disappearances as an offence distinct from any other kidnapping.

And then there were some external factors involved.

A group of experts working with the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights said in September 2012: “We acknowledge the security challenges faced by Pakistan…However, according to the 1992 Declaration for the Protection of All Persons Against Enforced Disappearances, ‘no circumstances whatsoever, whether a threat of war, a state of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked to justify enforced disappearances.’”

This declaration was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly -- that includes Pakistan -- in 1992. Among many other things, it states that “any act of enforced disappearance is an offence to human dignity.” It also condemns such acts “as a grave and flagrant violation of the human rights and fundamental freedoms proclaimed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”

United Nations has been repeating the same stance since then. In September 2020, human rights experts associated with it condemned “in the strongest possible terms the enforced disappearance of [Idris] Khattak.” They said that “Pakistani authorities must produce him [in a court of law] and guarantee him a fair trial.”

Khattak, a former consultant for Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, was taken away from his home town of Swabi in Khyber Pakhtunkwa allegedly by the Military Intelligence personnel on 13th November 2019. It took the government seven month just to acknowledge that he was in the custody of security agencies.

Between 2012 and 2020, human rights organizations and foreign governments have urged Pakistan on multiple occasions to take some concrete steps to end enforced disappearances. This pressure has been one of the main factors behind the drafting of law by the government.

The draft prepared by the human rights ministry proposes to criminalize enforced disappearances by amending the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) and the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPc). It suggests that enforced disappearances be categorized separately from the offence of kidnapping since the officials of the state are usually found to be involved in it. It also allows the registration of a criminal case against law enforcement and intelligence personnel suspected to be involved in an enforced disappearance.

After this draft was prepared, it was sent to the federal law ministry and interior ministry for a review in January 2019. The two ministries have shown serious reservations about it. “Interior ministry believes the law passed in its present form could be used for defaming intelligence services,” says a government official working in interior ministry.

In theory at least, that should have been the least of interior ministry’s concerns since its most fundamental mandate is to ensure rule of law across Pakistan. It also has limited authority over intelligence agencies as it controls only the Intelligence Bureau -- one of the many intelligence agencies operating in the country. Others are mostly associated with the military and are directly answerable to the military high command.

The military, however, is of the view that intelligence agencies associated with it have nothing to do with a lot of enforced disappearances. Last year it set up a special cell to look into the cases of enforced disappearances. This cell concluded that many of the cases could be attributed to factors other than the operations of intelligence agencies. “More than 2000 [missing persons] cases [pertain] to criminal kidnapping, radical youth joining militant camps and groups and people going underground on their own,” says an official familiar with the review.

This conclusion is a major hindrance to the presentation of the draft law before the parliament. “The interior ministry’s belief that this law will give a bad name to the intelligence agencies is primarily a reflection of the opinion of the security forces,” says an interior ministry source as he explains the causes of delay in the passage of the law.

Also Read

Restoration of local governments in Punjab: Justice delayed is justice denied

The human rights ministry, in the meanwhile, has come up with another suggestion: that the government sign the international convention for the protection of all persons from enforced disappearance. The ministry believes this will alleviate some of the pressure that Pakistan is facing from the United Nations and other states over the issue.

Missing intentions

Thousands of people have gone missing from different parts of Pakistan since 2001. In recent years, most such disappearances have been reported from Sindh and Balochistan.

The Voice for Baloch Missing Persons, an organization set up by the families of people gone missing from Balochistan, reports a total of 6,000 disappearances from that province. It also states that 1,400 Baloch missing persons have been found dead since 2009 – with their mutilated bodies having been discovered from unpopulated places.

In Sindh, where the government has recently banned several Sindhi nationalist organizations, 152 people are reported to have gone missing over the last few years. According to the Voice For Missing Persons of Sindh, a human rights group, these missing persons are mostly political activists.

Justice (retired) Javed Iqbal, chairman of the government-appointed commission on enforced disappearances, however, disputes these claims. He recently stated that around 2,141 people were reported to be still missing from across Pakistan and reiterated what the security agencies say: that many of these people have either joined militant groups of various ideological hues and religious and sectarian persuasions or they have gone abroad.

Human rights activists, on the other hand, publicly accuse the security and intelligence agencies of being responsible for enforced disappearances. They claim this does not need any proof because only those people go missing who have some real or perceived history of criticizing or opposing the state’s policies. According to them, almost all missing persons can be placed in four broad categories: those directly and indirectly associated with separatism in Balochistan; those linked to the banned religious and sectarian organizations; the proponents of Sindhi nationalism; and the adherents of liberal and leftist ideologies.

The law drafted by the government is not even needed if the ruling party has a serious intention to do something about enforced disappearances. These disappearances are already a crime under the Pakistan Penal Code. All such cases can dealt under the same law that governs kidnappings: Salman Akram Raja

Dr Tariq Hassan, a Pakistani academic working at the Harvard University, endorses this assessment albeit in an oblique way. In a 2011 paper, titled Supreme Court of Pakistan: The Case of Missing Persons, he writes that a former Chief Justice of Pakistan, Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, was at one stage investigating some 600 cases of enforced disappearances. He reports Chaudhry as stating that the Supreme Court had overwhelming evidence of intelligence agencies’ involvement in detaining “terror suspects and other opponents”.

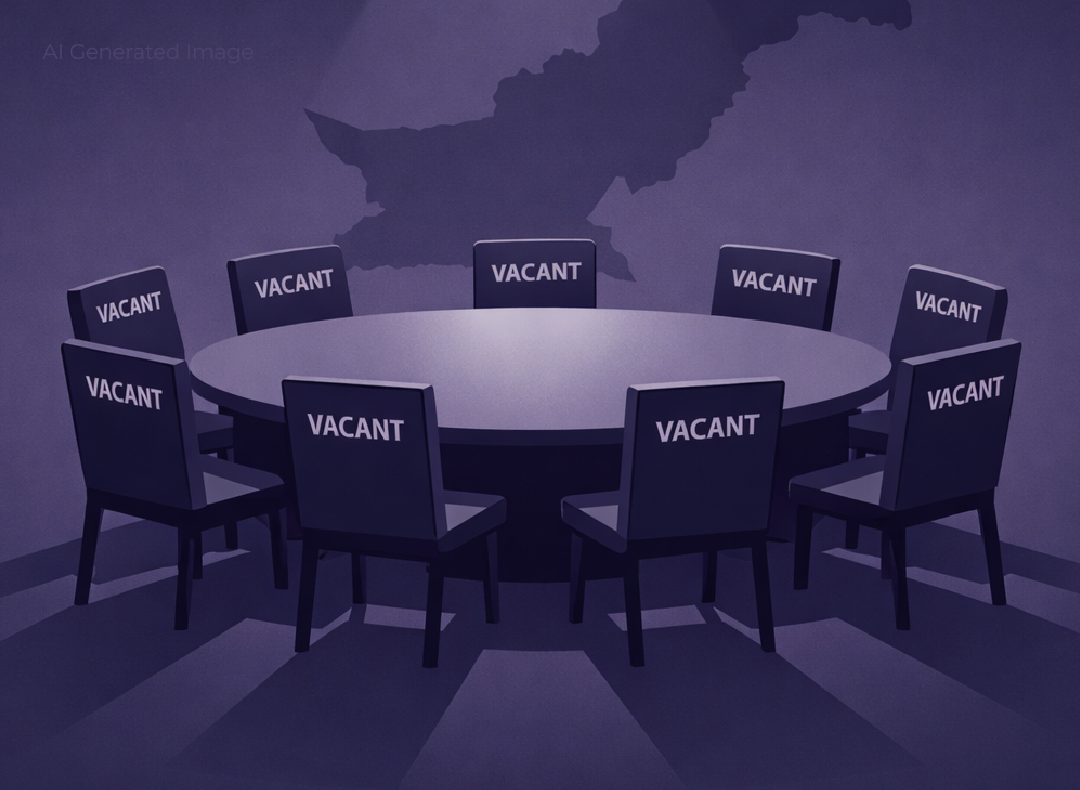

Given the alleged involvement of intelligence agencies in enforced disappearances, lawyers and human rights activists do not expect the PTI government to provide any relief to the missing persons and their families. Supreme Court lawyer Salman Akram Raja believes the law drafted by the government is not even needed if the ruling party has a serious intention to do something about enforced disappearances. “These disappearances are already a crime under the Pakistan Penal Code. All such cases can dealt under the same law that governs kidnappings,” he tells Sujag.

Commenting on the government’s reluctance to have its draft law passed by parliament, he says “the inordinate delay in this means the government is not serious”. Otherwise, he says, “it does not take two years to pass a law.”

Hina Jilani, a Supreme Court lawyer and the chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), categorically states that the PTI government is helpless in doing anything about enforced disappearances. “This issues was never within the government’s power to handle,” she says. “It is always controlled by the military and its intelligence agencies,” she adds.

In a phone conversation with Sujag, she argues that the question that lies at the heart of the problem is not whether we have a specific law on enforced disappearances but whether intelligence agencies could be brought within the purview of the country’s legal and judicial system. “We need to develop a system where the military and its intelligence agencies do not operate with impunity but are made accountable to the elected authorities,” she says.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 30 Jan 2021, on its old website.

Published on 10 Jun 2022