Pakistan has set lofty energy targets of increasing the share of renewable energy to 60pc by 2030 to achieve its net zero emissions target under the Paris Agreement. But to achieve this target, it needs $9.7bn to $14.4bn per year to finance green energy and nobody knows about the possible source of this huge amount. Green entrepreneurship in climate adaptation and mitigation sectors is being supported by climate funds from the governments as well as local and international initiatives, such as DAI’s Climate Finance Accelerator, Acumen Fund and USAID’s Private Financing Advisory Network, as well as commercial banks and venture capitalists. However, such committed international climate funds are not very common,

Clean-tech and finance -- chicken and egg story

Most entrepreneurs in the clean energy complain that their scale-up is stymied by the lack of funds. On the flip side, investors, commercial banks and climate fund managers also rue lack of investment-ready companies with robust models and scalable operations.

To fill this lacuna, there is a trend in Pakistan, especially within multilaterals, of SME capacity-building and investment facilitation initiatives. For instance, the Pakistan Private Sector Energy project, funded by USAID and jointly implemented by UNIDO and the Private Financing Advisory Network has raised over $3bn in climate finance and built a pipeline of almost 53 diverse clean-tech projects vying for investment.

“We are working on improving the financial literacy of clean-tech entrepreneurs as in the competitive investment space having a working prototype is not enough for money flow. Without this, either their business will run out of cash before they can scale or they won’t know how to effectively manage financing,” says Ahmed Ammar Yasser, the chief of party, Pakistan Private Sector Energy (PPSE) Project.

However, the initiatives like the PPSE project are a drop in the ocean in context of the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) 2021 report which says that Pakistan’s energy transition alone will require $101bn by 2030 and additional $65bn by 2040.

Shah Talha, the CEO of Mode Mobility, an SME creating ergonomic electric two-wheelers in Pakistan, considers climate finance crucial for two-wheeler EV start-ups.

“With global interest in EVs rising, government subsidies for them are boosting competition. Accessible climate finance at reduced rates can address challenges like funding research and development (R&D), localising manufacturing, building charging infrastructure, and driving consumer education. This would enable us to enhance technology, affordability and market reach,” adds Talha.

The Question of Capacity

Building a climate finance ecosystem requires efforts by the private sector, multilaterals as well as the public sector. The question arises about the capacity of each of these stakeholders and how they can support one another to nurture an ecosystem building climate resilience.

The global narrative on climate justice also stipulates that the larger emitters of greenhouse gases (GHGs) should bear the brunt of climate financing as they are the ones who profited most from fossil fuels. A study by the International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2021 has found that the private sector is a critical player in the climate action space and 100 companies are responsible for 71pc of industrial greenhouse gas emissions since 1988; accounting for 1 trillion tons of emissions.

While the government needs to do its part in setting a regulatory and policy framework amenable for clean-tech companies, having democratic funding, public-private partnerships are a crucial part in boosting this ecosystem.

Climate Funds and Random Investment

The bulk of investment to clean-tech SMEs is currently coming from miscellaneous investors and venture capitalists rather than dedicated climate funds as Pakistan is in its nascent phase when it comes to green finance. Even the country’s largest climate finance tranche, the Green Climate Fund of $197m has only approved funding of just $4.6m for five projects, three for adaptation and two for mitigation.

CEO of ezBike, Muhammad Hadi says the $1.5m his company has raised cannot quite be called ‘climate finance’ as it was in fact equity capital from venture investors.

“The lack of available climate finance makes us dependent on equity financing as a means to scale our business. This makes capital raising much more challenging while it also affects growth,” he adds.

On the other hand, the climate finance architecture is sophisticated, assessing each country’s risk profile and climate vulnerability scores.

“Just because Pakistan is one of the most climate-vulnerable countries does not put us on climate funds priority list, we are competing with other emerging economies such as Thailand, India, Bangladesh, Brazil, etc. Project proposals need to be competitive and backed up with evidence and data as funds go to the strongest proposals,” says Khurram Lalani, a climate finance expert.

While venture capitalists primarily look at demand, market niches and gaps, climate finance is driven by supply more than market trends. The available funds are quota-based and one can decipher which climate rationale makes the most business sense in terms of scale and impact through assessments. The common denominator though remains the return on investment (ROI). Miscellaneous investments in clean-tech assess the risk-return of companies primarily; climate funds are looking at the risk-return of entire countries.

Opportunities and Bottlenecks

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the average cost of reducing emissions in emerging economies is estimated to be around half the level in advanced economies. Clean energy investment in developing countries is an especially cost-effective solution to tackle climate change.

“Integrating sustainable, smart choices into new buildings, factories and vehicles from the outset is much easier than adapting or retrofitting at a later stage,” says the report, Financing Clean Energy Transitions in Emerging and Developing Economies, of the IEA.

In fact, action on emissions in emerging economies is so cost-effective that it is estimated that $1 of investment in clean-tech in economies such as Pakistan has three times the ROI as compared to developed economies.

Despite all these positives, the rationale behind investment in emerging economies’ clean energy transition is quite complicated. For instance, according to Pakistan’s NDCs in 2021, “A whopping 300% growth in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions between 2015 and 2030 was estimated based on a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate of 9% and increased reliance on fossil fuels,” says a UNDP report, Financing Climate Action in Pakistan: Solutions and Way Forward, published in 2022.

While the NDCs stipulated at least a 20pc reduction of GHG emissions by 2030 (subject to the availability of international grants), even this lofty goal cannot counter the damage done by the anticipated exponential increase in emissions this decade.

Untapped Solar Energy That Needs a Boost

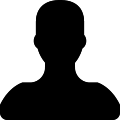

Much of Pakistan’s energy comes from fossil fuel generation and amidst the economic turmoil and high import tariffs, the energy crisis and inflation have led to a shift towards domestic solar energy use. Trying to cope with skyrocketing electricity bills, the consumers are going for solar energy.

Over the last decade, the cost of solar energy has come down 90pc and proved itself to be a reliable technology. According to Shazia Khan, the co-founder of solar company, EcoEnergy, solar energy has been accepted as a solution by the people who want reliable power. However, despite the cut in cost, it’s still expensive for homes and businesses as a solar system costs around $6,000 to $10,000.

“There’s a missed opportunity due to lack of climate finance. We could be reaching a far greater percentage of the population at a much faster rate. In Pakistan, the number of people installing solar is ever increasing but it is limited to the ultra-wealthy because of the high cost,” explains Khan.

While there is a marked consumer culture shift, solar energy only comprises a small share of Pakistan’s energy mix. According to the 2021 yearly report of the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (Nepra), Pakistan’s total installed power generation capacity is 39,772MW, of which 63pc comes from thermal (fossil fuels) and only a little under 2pc from solar.

Khan considers lack of climate finance responsible for it. Commercial banks in emerging markets like Pakistan are risk averse and make financing solar solutions a painful, lengthy process, with few loans approved. According to solar power entrepreneurs, funds can provide concessionary financing to make solar affordable to even marginalised consumers.

If the country needs to meet clean energy transition needs, the potential of solar energy has to be realised. Entrepreneurs such as Khan working on the ground can help shape policies on consumer and commercial solar, such as incentivising government solar PPAs or bolstering domestic solar uptake through installment schemes. Despite high import costs and a destabilized economy, many solar installers are successfully running their business and helping the clean energy transition.

That being said, one of Pakistan’s biggest hurdles to mass solar electrification is the high cost of imported solar equipment and panels. Many companies attest that domestic manufacture of solar parts would not only indigenise the market, create jobs and self-sufficiency but also make solar more affordable, for households, government and corporations. The World Bank reports that Pakistan has a potential of 40GW of solar power and has set a target of achieving 20pc of its electricity from renewable sources by 2025. Last year, Pakistan imported solar panels of 2.4GW having an import value of about $1.2bn, and solar imports are estimated to rise to around $1.8bn.

Solar-powered EVs and related challenges

The transport sector is responsible for one-quarter of emissions that are estimated to double by 2050. According to the Institute of Urbanism, the transport sector accounts for 43pc of emissions and smog in Pakistan while carbon emissions from vehicles are set to increase by 300pc over the next 15 years.

As a step towards getting rid of copper mining and fossil fuels, opportunities exist in the carbon finance space and the solar-powered EV space for rickshaws and motorbikes. “Electric cars are out of budget for most Pakistanis but electric motorbikes cost about the same as traditional motorcycles. People are not switching to them because electricity is more expensive than gas in Pakistan. Climate finance could be used to create solar-powered EV charging stations,” says Shazia Khan.

Electric mobility entrepreneurs have shared opportunities and challenges to solar power entrepreneurs in terms of high-import prices for parts that are not manufactured locally. While this tide is slowly shifting as more companies venture into this sector but they face challenges from the established transport sector.

One of the biggest challenges this sector faces, according to Yasser, is that the two-wheelers in the market are primarily run by the same leasing model as established fossil fuel-driven two-wheelers.

“For EVs to be profitable and affordable, we need to understand the capital requirement of leasing companies. There are monetary gaps for EVs that need to be filled,” adds Yasser.

EV entrepreneurs such as Talha note that in the current landscape, operations are positioned alongside traditional mobility companies whose environmental impacts are detrimental. In absence of dedicated climate finance places, these companies are on an equal footing with traditional transportation companies despite EVs commitment to eco-friendly solutions. This lack of distinction hinders their ability to highlight the positive environmental contribution that they are striving to make, especially when it comes to investors and commercial banks.

Also Read

Solar energy shift: A brighter future for Pakistan textile industry

However, if climate finance becomes accessible, this would enable companies to carve out a niche, creating a separate field where they can showcase green initiatives. “Climate finance can accelerate our growth, especially in the area of EV infrastructure. Blended finance structures in particular can help reduce the cost of capital and derisk early-stage green businesses to make them bankable,” comments Hadi.

Opportunities in waste management sector

Plastic pollution is another major problem for Pakistan in dire need of adaptative technologies and interventions. Pakistan generates approximately 48 million tonnes of municipal solid waste (MSW) and industrial processed solid waste. Several companies have appeared to tackle net-zero and circularity challenges by working closely with multinationals and large corporations.

ISP Environmental Solutions, led by Zille Mariam, is one such company founded in 2018. The start-up is working towards creating solutions and strategies that employ integrated solid waste management (ISWM). Mariam believes that ineffective waste management can be stopped with the right deployment of resources, particularly climate finance.

“In Pakistan, so far, there’s no site for integrated waste management where sustainable services are provided. We need climate financing so that companies like mine can provide waste management solutions to the industrial sector,” she says and adds that processing of waste is an ongoing process in need of infrastructure development and running capital that only dedicated climate funds can ensure.

Good news for green entrepreneurs is the establishment of the Climate Finance Unit (CFU) under the direct supervision of the Ministry of Climate Change as a dedicated office to coordinate with relevant stakeholders and facilitate the ministry in looking after global climate finance opportunities.

The CFU would not only work closely with federal and provincial governments, UN agencies, and other multilaterals but also inculcate insights and on-ground experiences of the entrepreneurs that can help shape deployment strategy and regulatory framework.

Published on 22 Aug 2024