Allah Rakhiyo, 55, has a darkish complexion and greying hair. In September this year, he is sitting at the foot of Karoonjhar range looking at the water flowing from the mountains of varying heights around him.

This range is located a few kilometres southwest of Nangarparkar town which is just 16 kilometres from Pakistan-India border in Sindh’s eastern district of Tharparkar. It houses about 108 ancient worship places of Hindu and Jain faiths. The lack of care, though, has reduced many of them to a rubble.

Stretched over 19 kilometres and standing at 305 metres above the sea level, the range contains huge deposits of granite, a decorative stone used in construction. The first contract to mine this stone in recent history was awarded in 1988 by Sindh government to a company called Millrock. It started extracting granite after obtaining a bank loan but soon left Karoonjhar.

Then in 1990, another company, Pak Rock, began mining granite from these mountains. Ghulam Mustafa Khoso, who used to work with that company as an engineer, says it would mine anywhere between 1,000 and 2,000 tons of granite rock every month by using dynamite blasts. This method, according to Khoso, not only damaged a large quantity of the quarried stones, it also disturbed the natural environment of the range.

Some local residents pointed out these problems in a petition they filed at the Supreme Court in 2010. They informed the court that granite excavation could cause the collapse of Durga Mata’s ancient temple in Choriyo village located within the mountains. The court accepted their petition and ordered the company to stop its operations.

Before that, however, another mining company, Koh-e-Noor Marble, had also started extracting granite from Karoonjhar under several government-sanctioned contracts. Later, through an agreement, it sublet its contracts to the Frontier Works Organization (FWO), the engineering and construction division of Pakistan Army, which is now engaged in large scale stone mining in the range.

Similarly, when construction of several small dams began in Tharparkar in early 2019, their builders also started using Karoonjhar’s stones as this involved low transportation charges. They had to pay only 1,500 rupees per truck to transport stones from the mountain range to the dam sites. In contrast, it cost them 60,000 rupees to bring the same amount of stones from Jamshoro district near Hyderabad.

The residents of the area in and around Karoojhar protested strongly against this use of local mountains. Their protest later turned into an impressive social media campaign. Buoyed by popular support for the issue, some lawyers associated with Tharparkar Bar Association filed a petition before the Hyderabad circuit bench of the Sindh High Court which stayed the quarrying of stones for the dams on November 14th, 2019.

The court order, however, did not stop FWO’s stone mining activities. It is, therefore, still excavating granite rocks on a large scale -- using dynamite.

This makes Rahkiyo extremely angry and he complains that people hailing from other areas are wreaking havoc with the mountains of Karoonjhar. And they are doing so, as he puts it, “to use these stones to adorn the toilets of the rich”.

The ‘range’ of possibilities

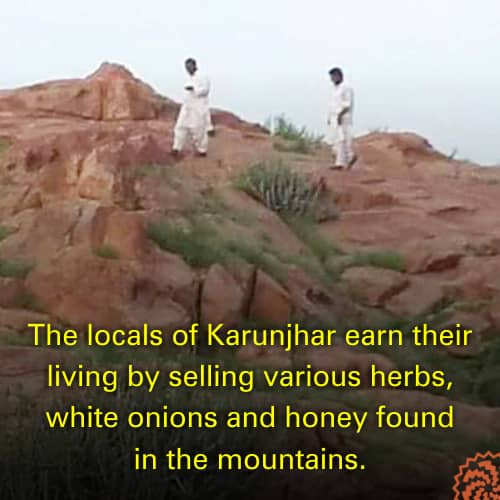

Rakhiyo deems Karoonjhar as a “living” mountain range with a “beating heart”. The range, according to him, provides a lot of necessities of life to those living in and around it.

Using another metaphor to highlight the importance of Karoonjhar, he says it gives “1.25 kilogram gold to the locals every day.” In other words, its inhabitants make a large part of their living from this range because it contains a wide variety of herbs, white onions and honey.

Rakhiyo vows that he would not let anyone destroy these mountains because “when our wells went dry, it was Karoonjhar which provided us water”. So, he says, “if this range did not leave us alone in difficult times, how can we leave it alone [to be destroyed through granite mining]?”

A few years ago, Rakhiyo launched a movement, all alone, to protect Karoonjhar from the hazardous effects of mining. Now, he says, his campaign has succeeded in winning support from a wide range of people from across Sindh.

Referring to this support, he says: “Local people, both Hindus and Muslims, neither cut a tree from the mountains nor they use it as firewood. So, if we don’t cut down Karoonjhar’s trees [to meet our needs], how can we tolerate the destruction of the entire range which is home to thousands of trees.”

He complains that the use of dynamite blasting for stone mining has reduced the population of vultures in the range. Moreover, many wild animals found in its mountains – such as deer, stags, leopards -- and many local birds are no longer visible here, he says.

Mining operations, according to him, are similarly causing gugral trees to wither away. Soon “they will become a thing of the past”.

A local researcher, Mushkoor Fhalkaro, has similar views about Karoonjhar. One of the main features of this mountain range, he says, is its diverse ecosystem. “If one mountain has a green cover of Chandoor trees, another is the habitat of vultures. Likewise, if silt-eating flies are found on one mountain, the other is the abode of bats,” he says.

Fhalkaro refers to a recent study on Tharparkar conducted by a private company, Engro, which says that granite rocks in Karoonjhar go as deep into the earth as 990 feet. These deep rocks, he says, serve as a natural defence system that protects Tharparkar from the intrusion of seawater and its negative effects. This explains why geologists warn that an unabated mining of granite rocks will allow the Arabian Sea to make groundwater brackish not only in Tharparkar but also in its northern district of Sanghar.

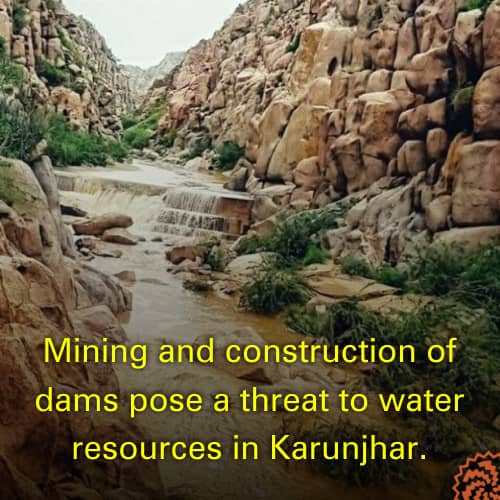

The local population fears that the mining of stones and construction of small dams will threaten Karoonjhar’s water resources as well. They say the range has many natural springs which generate water all year round. Its mountains, in fact, are the only source of clean drinking water in the entire Nangarparkar area because water from the wells located in them is sweet while groundwater in the adjoining areas is brackish and, thus, unusable.

Rakhiyo says people in the olden time used to dig wells and ponds in the mountains of Karoojhar to store rainwater. Many of those wells and ponds still survive. These are called ‘sar’ in local language – such as Bhode Sar, Ram Sar etc. Sindhi Sufi poet Shah Abdul Lateef Bhittai has also mentioned them in his poetry 300 years ago.

But their water does not suffice for all the local needs. To meet the drinking water requirements of people living in the area, Sindh government -- in collaboration with the World Bank -- has launched a project to build 21 small and large dams in different parts of Tharparkar, including in Karoonjhar.

Zulfiqar Khoso, a local young man running a social media campaign on environmental issues, is unhappy with this project. He claims the dams are being constructed in the absence of a scientific feasibility study and without any input from the local residents. They could stop the natural flow of water from the mountains, he says.

These dams, in his opinion, could have benefited the local population only if their sites were suitably selected. “A number of them are being built at unsuitable sites and, therefore, will not withstand the intensity of water flowing down from the mountains,” he says.

Published on 4 Nov 2021