Magan, 37, teamed up with his 16-year-old wife Sonari a few weeks ago to build a mud house so that they could have a roof over their heads during the rainy season. Magan now lives alone in that house because Sonari, pregnant for several months, has died.

He says his wife had a sudden and severe pain in her abdomen a few days ago. He immediately started looking for a vehicle to take her to a midwife, Momal Mai, who lives in a nearby village but he could found nothing because it was very late in the night. So, Sonari kept screaming in pain all night and Magan could not do anything but give her assurances that she would be alright.

Early next morning, he took her to Mai in a motorcycle rickshaw. Sonari was unconscious at that time and she had also lost a lot of blood. Mai, therefore, refused to treat her and told Magan to take her to a nearby hospital.

He took Sonari in the same rickshaw to Marvi Clinic in Umerkot, a city in eastern Sindh, where a doctor removed a dead fetus from Sonari's womb but she also died during the procedure.

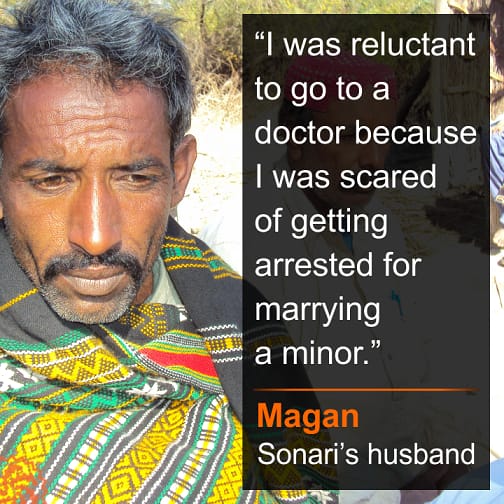

Magan, a resident of Jainro Daro village, located 22 kilometers south of Umerkot, belongs to the scheduled caste Hindu Bheel community. His parents have died and he works as a daily wage laborer. He had married Sonari just a year ago.

Although his wife had been complaining of abdominal pain and bleeding for several days before his death, Magan did not take her to a doctor because, he says, he had no money. “I am so poor that my pregnant wife used to work alongside me in a brick kiln so that we could make ends meet,” he says.

It was not poverty alone, though, that stopped him from taking Sonari to a doctor. “I was also reluctant to go to a doctor because I was scared of getting arrested for marrying a minor,” he says. Gamnu Oad, a resident of his village, had recently spent two nights in a police station for the same crime, he adds.

Medical risks facing young mothers

Gynecologist Dr Najma Ali has worked in a number of public health facilities in Umerkot, Tharparkar and Badin districts of Sindh. She confirms that underage pregnant girls belonging to scheduled caste Hindu communities are often taken by their families to untrained midwives because they fear that going to a doctor could land them in legal trouble.

She herself has helped police arrest some people involved in marrying off underage girls. “I did this so that these communities refrain from such marriages for the fear of being arrested,” she says but admits that underage marriages continue nevertheless.

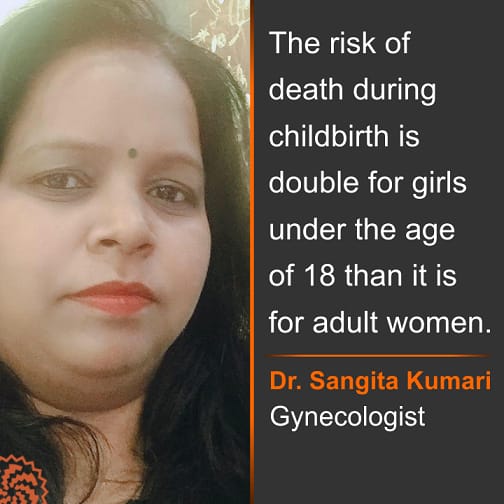

Another gynecologist, Dr Sangeeta Kumari, who works in Mirpur Khas city, points to the same problem and says the risk of death during childbirth is double for girls under the age of 18 than it is for adult women. The main reason for this, according to her, is that weak and immature bodies of these girls do not have the capacity to adapt to the physical changes caused by pregnancy. “The household work and labor these girls are employed in is always beyond their physical capacity but at the same time the food given to them is highly inadequate for their energy needs,” she says.

How to stop child marriages?

Krishan Bheel, a resident of Umerkot, teaches at a government school and spends his spare time as a social worker. Sonari’s death, according to him, is not the only incident of its kind. His two nieces, Radha and Kasturi, have also lost their lives due to early pregnancies, he says. In Magan’s village alone, he says, four girls besides Magan’s wife have died in a few months due to the same problem.

The main reason for underage marriages in his Bheel community, according to him, is the centuries-old belief that letting girls grow old without marriage is a sin. But, he says, those who profess this belief do not realize that “girls like Sonari are suffering” because of it.

Krishan also formed an organization along with some local youth to prevent underage marriages among scheduled caste Hindu communities. “But local pundits were so offended by this initiative that they pressurized us through the elders of our community to shut it down,” he says. So, “we had to stop our work”.

Muhammad Hassan Khaskheli, a lawyer working in Badin’s district courts, on the other hand, believes it is not the duty of any social workers or organizations to prevent underage marriages. “It is the responsibility of the government,” he says.

The government is not fulfilling this responsibility though. “Both the provincial and the federal governments have enacted laws about marriages of Hindus living in Pakistan which clearly state that the bride and the groom should not be less than 18 years of age at the time of their marriage. Maternity deaths of young girls, however, prove that these laws are not being implemented,” he says.

Khaskheli believes that, in order to discourage underage marriages, the government must take action against those pundits who solemnize such marriages. “The government should also create public awareness about the dangerous medical effects of these marriages so that parents think a hundred times before marrying off their minor daughters.”

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 13 Aug 2021, on its old website.

Published on 22 Mar 2022