Tabasum Bibi, a 40-year-old resident of a village in Kurram district, used to create and sell various handicraft items crafted from a plant called ‘Mazri’. However, her source of livelihood has now vanished, leaving her without a job.

Tabsam is the wife of a grade IV employee and a mother of four children. She shares that she used to make goods with Mazri, which were then purchased by city shopkeepers for resale, bringing in a decent income. Over time, however, Mazri became scarce and expensive. Additionally, the handicraft market wasn’t providing adequate compensation. Frustrated with these circumstances, she eventually had to give up this occupation.

Not just Tabasam but many other women in the area who used to create household items with Mazri have also abandoned this work.

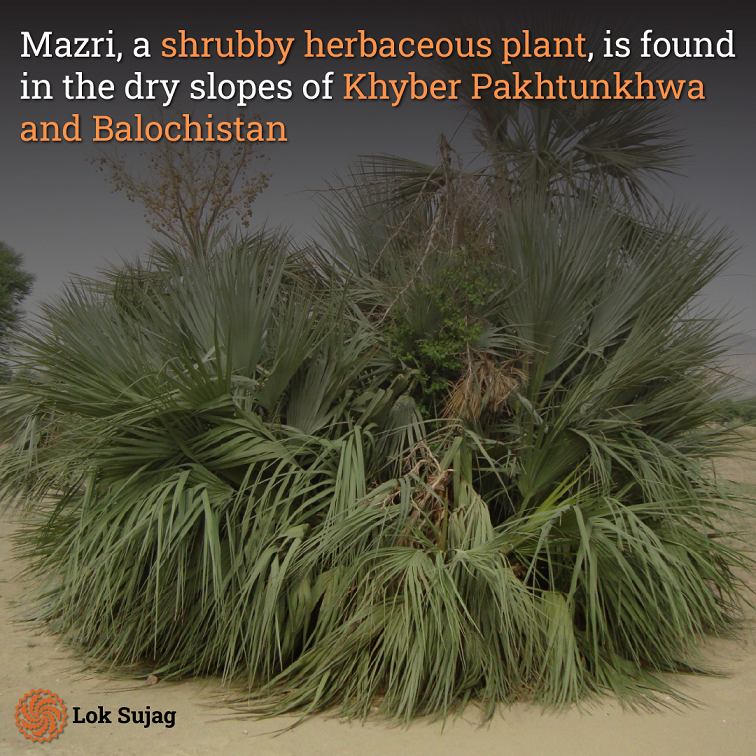

Mazri is a shrubby herbaceous plant commonly found in the dry slopes of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. Its leaves resemble palm fronds. In English, it is known as ‘Aich’, Urdu as ‘Mazri’, and Pashto as ‘Mazriya’. In Balochi, it’s called ‘Pesh’, and in Saraiki, ‘Pece’.

The Mazri plant bears small, round, earth-coloured fruits. In Balochistan, its soft branches, known as ‘Kelarr’, are used for frying. Its leaves are skillfully woven to create mats, bedspreads, hats, and baskets, among other items. Some of the 36 products crafted from it also utilise Mazri wood.

A WWF Pakistan report states that in 2004 around 65,000 people were engaged in various activities related to Mazri, including cutting leaves and wood, bundling, trading, and crafting household items. About 78 per cent of these individuals were women. However, the situation has changed since then, with most people no longer holding these jobs.

Nuzhat Amin manages the program at an NGO called ‘Khwanda Karo’ in Peshawar. Her organisation focuses on teaching handicraft skills to women from marginalised regions of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

She highlights that the products crafted by women in this province are well-regarded in large cities and even internationally. These items, particularly in Britain, fetched reasonable prices, offering women employment from their own homes.

Nuzhat confirms that many skilled Mazri workers are currently unemployed.

“We used to have 25 women in District Karak, but now there are only eight, mainly because the work is very physically demanding, and the pay is quite low.”

Rashid Hussain is the Director of the Non-Timber Forest Product (NTFP) Department of Forests, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. He explains that Mazri production is more common in rainy areas. The government-designated protected forests in Kohat are the main areas for Mazri cultivation. Production in these areas has remained steady, whereas other regions have experienced decreases.

In 2018-19, the production of Mazri was 700 tons, with a selling price of Rs 20 per kilogramme (kg). In the following year, 2019-2020, production increased to 850 tons. As for 2020-2021, the production remained at 1,508 tons.

Iqbal Hussain, based in Kurram District, has been engaged in the Mazri business for 25 years. He purchases Mazri leaves from various areas and sells them in the market.

He explains that except within the government-designated protected area, the production of Mazri has significantly decreased, leading to a rise in its price. Some years ago, a bundle of Mazri containing around 80 leaves was priced at Rs 50. Today, the same bundle costs Rs 300. This decrease in production has directly impacted the workers in the field.

Dr Abdullah conducted research on Mazri during his PhD at Quaid-e-Azam University and is now continuing his studies in Europe.

He notes that the decline in Mazri production began during the Afghanistan-Russia war when Afghan refugees arrived in large numbers to the former FATA and adjoining districts. Mazri is also found in Afghanistan, and Afghans were skilled in creating household items with it. Mazri was commonly used by these people, even as fuel for their homes.

Dr Abdullah points out that due to the growing population, Mazri plains are being converted into farms and settlements. Furthermore, the sapwood tree has contributed to the decrease in Mazri production. This tree is harmful to nearby plants, including Mazri.

Floods contribute significantly to the decline in mazri production, ranking as the third leading cause. Prolonged water presence in an area leads to the plant’s roots dying, causing damage to the crop.

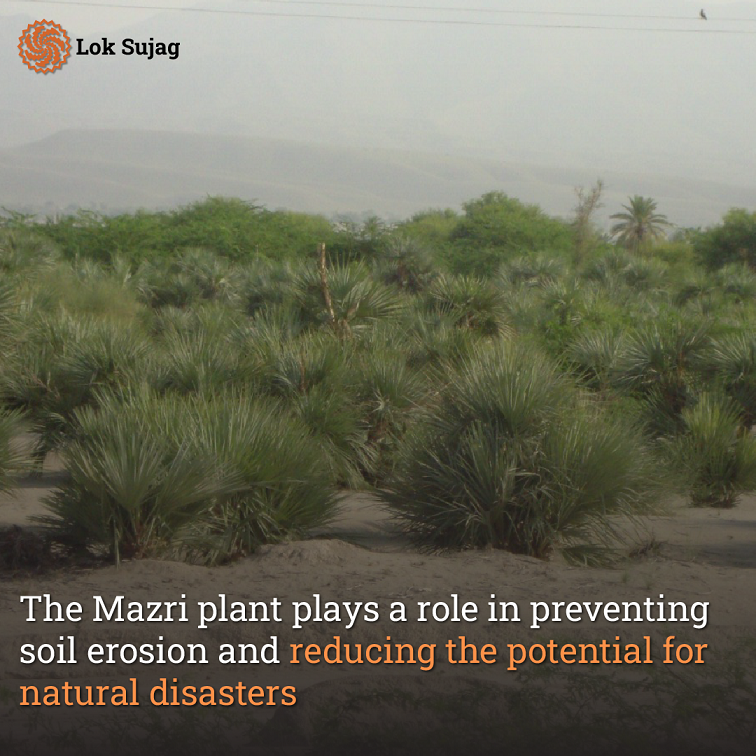

According to Rashid Hussain, the Mazri plant plays a crucial role in preventing soil erosion. It also helps extend the dam’s lifespan, strengthens sand dunes, and minimises the risk of natural disasters.

He further explains that the Mazri plant provides wildlife habitat, and humans and livestock consume its fruit. Additionally, Mazri finds use in numerous herbal medicines.

Dr Abdullah emphasises that Mazri can be a potent tool against climate change. If cultivated along roads, it can absorb vehicle emissions. To promote Mazri growth, the government should consider replacing eucalyptus trees along roadsides.

Also Read

Struggles of women labourers in Hyderabad’s vegetable market: Seeking recognition and fair wages

He also points out that brooms, hats, ‘hot pots’ for keeping bread warm, and ropes were traditionally crafted with Mazri. Although these items are still in use, they are now made from plastic, contributing to environmental pollution.

He also points out that women who crafted household items with Mazri gradually enhanced their work, adding decorative elements that increased the overall cost.

“Nowadays, you can find a plastic hot pot for keeping bread warm at a lower price of five or six hundred rupees, but a beautifully decorated Mazri hot pot won’t be sold for less than twelve or thirteen hundred rupees,” he explains.

Nuzhat Amin highlights the challenging nature of working with Mazri. Women who engage in this craft often develop blisters and callouses on their hands. She emphasises the importance of discovering new markets for these handicrafts.

This would not only help maintain women’s skills and provide employment, but it would also benefit the environment.

Published on 18 Aug 2023