The Thar Desert has been associated with drought for a long time but the four-year drought from 1998 to 2002 broke the 50-year record. As a result, the lower Indus delta also dried up.

The year 2000 was the peak of drought in Tharparkar district when 1.3m people were directly affected by hunger and related problems in various Sindh regions, including the desert. It resulted in loss of 127 human lives and 30 thousand cattle.

At the same time, the then chief executive of Pakistan Gen Pervez Musharraf visited the affected areas and he was told that “more than 28pc of the Thar population has moved to barrage areas while others are provided with ‘Langar’ and food/grain.”

Potable water situation in Tharparkar

The same year, a project was announced for the first time to supply water to Mithi city, the district headquarters of Tharparkar, which was completed in 2002. Meanwhile, digging of new wells continued with the support of the community.

Many regions in the world face drought, less rain and even no rain in the monsoon. However, there is neither a loss of a large number of human lives nor numerous cattle.

Out of the 17,7800 people of Tharparkar, only 8pc reside in cities whereas 92pc of them live in villages whose economy depends on rain. The total agricultural production of the district has 41pc millet, 33pc sugarcane, 13pc wheat, 9pc cotton and about 3pc sesame.

In terms of Sindh’s total livestock production, Tharparkar district contributes about 11pc in cattle (cows), 30pc in sheep and 17.6pc in goats. But in absence of rainfall, crops and fodder are available in only some areas.

Along with poverty, lack of medical facilities and saline underground water in the desert, there is no clean water available for crops, fodder and drinking. Lack of rain causes a famine-like situation that increases the death rate of humans and animals.

Water supply projects and resurging drought

In 2011, the PPP government planned to install 750 RO (reverse osmosis) plants, including 700 solar-powered plants, for $33m to provide potable water to the desert people in Tharparkar district. The project was to be completed in 2016.

In addition to these mega projects and submersible pumps of the district council and non-government organisations completed some projects of supply of many clean water in Thar.

Unfortunately, Tharparkar confronted a drought again in 2014. Rainfall decreased and the experts attributed it to the climate change. Hence, this drought continued till 2018.

The national media reported the Thar map on Nov 18, 2018 in this way: “Another newborn has died in Civil Hospital Mithi, which brings the number of children killed in Thar this month to 30, while malnutrition and epidemics have caused 549 child deaths so far this year. In Tharparkar, the worst drought and famine has left many villages empty as thousands of families have been displaced.”

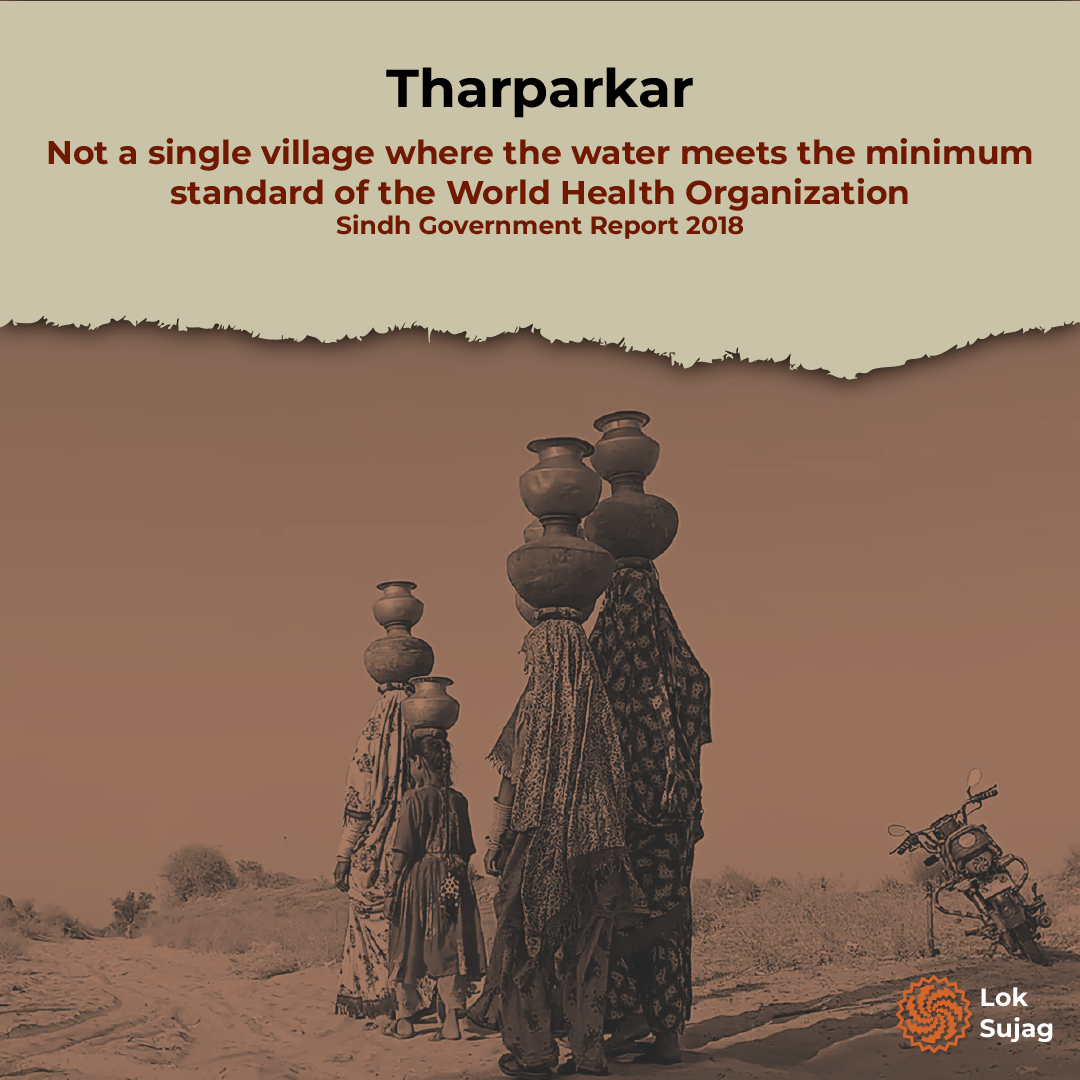

In 2018, the Sindh government prepared a report called ‘Assessment of Urgent Needs in Drought-affected Thar', whose authors wrote, “Due to low rainfall in recent years, about 60pc of the population has not been able to cultivate crops. They will hardly be able to feed their families once a day.

“The biggest problem here is water. None of the villages we visited have water that meets the minimum standards of the World Health Organisation.”

Big projects, big corruption

Most of the 635 RO plants installed by the Sindh government at a cost of Rs5.4bn in Tharparkar through a private company, Pak Oasis, were closed after some time and never became operational again.

Former Caretaker Chief Minister of Sindh retired Justice Maqbool Baqir visited Mithi in December 2023 and found Asia’s largest RO plant installed there in poor condition. He ordered an investigation against the plant installation company, Oslo.

Later, the provincial cabinet approved the restoration of Islamkot and Mithi RO plants at the request of the Public Health Engineering and Rural Development Department but both plants have not yet been made operational.

In March 2024, Public Health Engineering (PHE) and Rural Development Department Secretary Sohail Qureshi made a surprise visit to the Mithi RO plant. He admitted that the RO plant worth Rs1bn, which supplied 2m gallons of water per day, was shut down in 2019 due to lack of repair. He said that a few months back, he had released Rs100m for this plant’s repair but no work was done due to corruption and the funds were embezzled. At this, he suspended EXEN Aslam Dahri and Assistant Engineer Muhammad Idris from service.

The situation is similar at the rest of the 635 small and large solar RO plants being set up across the district whose maintenance is now entrusted to the Punjab Health Engineering and Rural Development Department.

Heavy cost of running RO plants

An officer in the Public Health Engineering and Rural Development Department, on the condition of anonymity, says Rs240m out of the total departmental budget of Rs500 goes into salaries. With the remaining amount, 50 plants will barely be able to operate as it costs Rs1.5m to 2m to restore a small RO plant. He says an RO plant of the capacity of 15,000 gallons per day was installed in every Thar village and the operators were posted to run it. Running each plant costs Rs2m to Rs2.2m per annum, including the operator’s salary.

The public health engineering department and district council installed submersible pumps in Tharparkar through separate NITs (notices inviting tenders) which directly drew groundwater (without treatment) through solar electricity or generator.

Tharparkar has more than 1,200 submersible pump schemes that are worth billions. In various Thar regions, this pump costs from Rs700,000 to Rs1.7m (according to the depth of underground water) but this water is saline and not potable.

Jagomal, a resident of Sadh village near Diplo city, says that social institutions have also installed submersible pumps in some villages, some of which have relatively less saline water that can hardly meet the needs of 15 houses.

According to an official in the public health department, there are a total of 832 RO plants in Thar and around 1,200 submersible pumps have been installed in the last five years.

“The department has a severe shortage of technical staff. There is only one assistant engineer and three sub-engineers, although area-wise, there should be more than 14 engineers and sub-engineers.”

He says the submersible pump is a failed scheme launched just to please people as canal water and RO plants are the solution to the Thar crisis.

Pipeline for canal water and failure of RO plants

Baqir Hussain Shah, assistant engineer of the department, says the water supply line built in 2002 from Nokot to Mithi provided fresh water from the canal to the latter and its nearby villages. However, the supply line meant for only one city was first extended to Islamkot and later to Nagarparkar and Chelhar in 2023.

“Due to the increased population and only one supply line, Mithi city, Islamkot and the middle population get water barely once a month. There are several problems with the blockage of Mithrao Canal (from which Mithi receives water), including 16-hour electricity outages on the rural feeder of the pumping station and the old pipeline.”

The Sindh government has allocated more than Rs1bn for this scheme in the current budget but now this matter has fallen prey to delay.

Ali Akbar Rahman has extensive experience in environment and water work in Tharparkar and he is also the chief executive of the Association for Water, Applied Education and Renewable Energy (AWAIR). He believes that the RO plant installation is the most modern and viable programme among all the Thar water supply projects.

“The work done by various NGOs on water projects is a separate Pandora's box. The number of taps and solar pumps etc in Thar villages are great in number but they lack mechanism.”

Unfortunately, this RO plant project could not be successful because of poor planning. This is because the public health engineering department has shortage of technical staff and it doesn’t have even a laboratory.

Another PHE department official says that the local officials had proposed to install a treatment plant on the water collected in Gorano Dam from Coal Block-II and supply it to the villages. This water can meet the requirement of the entire Thar but no one paid heed to this proposal.

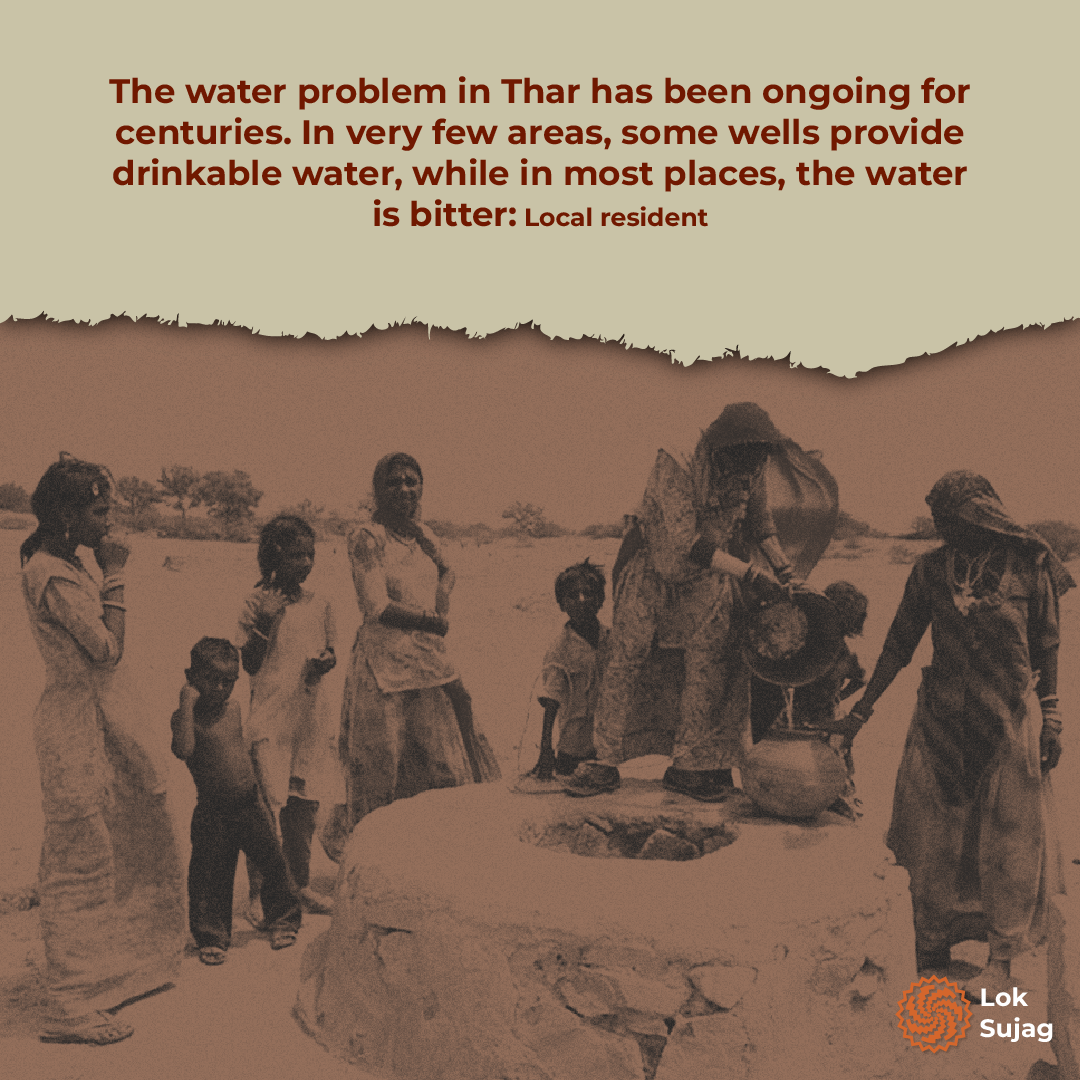

Sixty-seven-year-old Muhammad Idris is a farmer from the Kathu village in Mithi. He says the Thar water issue has been going on for centuries. Only a few of its areas have sweet water in wells while the others have a bitter taste. People here have been demanding a canal for decades, which would make the entire Thar green.

“They say India is irrigating the desert through the Indira Gandhi Canal and it has made it possible, why can’t we do the same?” he asks.

Those privy to information say that in 1991 when negotiations were being held in the Council of Common Interests on the formula for the distribution in the Indus River water, the representative of Sindh demanded water for Thar through a canal. But despite the agreement, nothing was done in this regard.

Rainee Canal project— a remedy for Thar water issue?

Water resources expert and consultant engineer Zafar Wattoo says the Sindh Rainfed Areas Authority (Sazda) launched a project to give canal water to the Tharparkar desert in 1993. It proposed building of a 500km long canal from the Guddu Barrage to Mithi.

In 2000, the federal government announced the Rainee Canal project from Guddu barrage and foundation stone of the canal was laid two years later so that the canal would reach Thar in the next phase.

According to Water and Power Development Authority (Wapda), the Rainee Canal would be supplied with 5,155 cusecs of water seasonally. The purpose was provision of irrigation water to the Nara region of the Rainee tract and storage of floodwater in the lakes.

According to the official website of the Wapda, the first phase of the Rainee Canal was launched with a length of 110km and a water capacity of 5,155 cusecs. According to the original PC-1, the total command area of the canal was 412,400 acres but Phase 1 would benefit an area of 113,690 acres with an estimated cost of Rs18.8bn.

Also Read

Thirst for justice: Thar’s solar RO dream dries up, leaving communities parched

Work on the first phase began in October 2002 and it was scheduled to be completed in June 2014 but the project got delayed. However, Wapda completed this part of the canal in January 2022 and handed it over to the Sindh Irrigation Department.

In June 2022, the Sindh government announced the completion of the second phase of the Rainee Canal or Thar Canal in August 2023 but its feasibility was not completed.

Consultant Nespak, Baraqaab, Rehman Habib (JV) Consultant were tasked with completing the feasibility report in 2021.

Ten days ago, the director of a consultant company, Engineer Zafar Wattoo, announced that the feasibility report of the Thar Canal had been completed.

“The Thar Canal will not only irrigate more than 250,000 acres of Rainee, Nara, and Thar desert but would also provide drinking water to more than 200,000 people and more than 500,000 cattle.”

After the failure of several projects, the Thar residents have now pinned their hopes on the Thar Canal for a solution to their water problem.

Published on 31 May 2024