The federal government is reluctant to pass a law that will amend the Christian Divorce Act and provide for a flexible pathway to a divorce.

The law was drafted by the federal human rights ministry in August 2019. After its drafting was completed, federal human rights minister Shireen Mazari publicly stated that it would be presented soon in parliament for approval. More than ten months later, it is still gathering dust in a bureaucratic cabinet at the federal secretariat.

Sources in the government and Christian community say the draft is facing stiff resistance from church leaders. They see its provisions as violating religious edicts known as Canon Code.

The clergy is not in the favor of giving married couples the right to divorce, says a church leader on the condition of anonymity. He explains that Christian religious leadership sees marriage as a sacrament – a union graced by divinity -- which cannot be ended by human beings. This union can only be annulled if one or both spouses are found to be violating religious terms and conditions under which it was formed, he says.

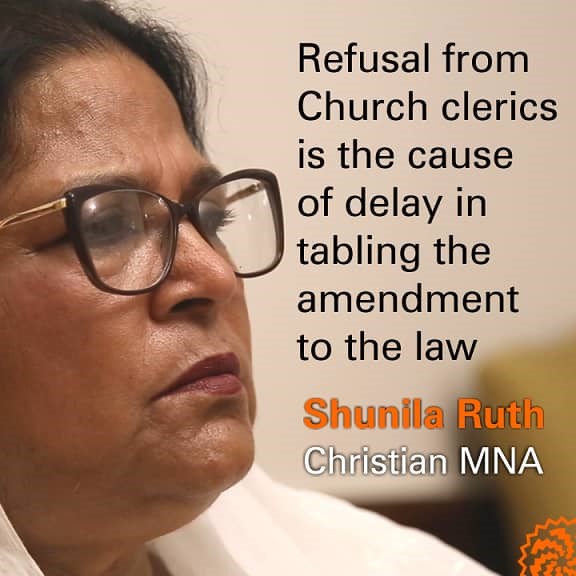

Shunila Ruth, a Christian member of the National Assembly belonging to the ruling Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), acknowledges the opposition the draft is facing. She says her party is not ready to present the draft in parliament until the clergy approves it with consensus. “We do not want to take the blame for interfering in the internal or family matters of Christian community,” she says. “That is why the approval of the law has been delayed.”

Officials working at the federal human rights ministry see this opposition as unreasonable. They claim the government has held nine consultative meetings with Church leaders and Christian-led civil society organizations to develop the draft. “Serious objections were raised about its contents in those meetings,” says a senior law ministry official. It was only after those objections were addressed that Shireen Mazari announced to take the draft to parliament, he says.

Zaiul Haq’s long shadow

Section 7 of the Christian Divorce Act, originally promulgated in 1869 during the British Raj, allowed courts in the Indian subcontinent to follow the English civil law while deciding divorce case involving Christian couples. For 34 years after the creation of Pakistan, this section remained a part of the law but then some bureaucrat at the law ministry pointed out that it presented a legal anomaly: it made the courts of a sovereign country to follow the laws of another country. So, the military government of General Ziaul Haq removed Section 7 of the act through a presidential order in 1981.

Sabir Michael, a Karachi-based teacher and human rights activist, says the reason for removing the section was not legal but political. Just as Ziaul Haq was Islamizing the Muslim part of Pakistani society, he also wanted to Christianize the Christian Pakistan, he says. This, according to him, explains why Ziaul Haq removed the section and gave the clergy a predominant role in Christian family affairs. The government was “aided and abetted in this endeavor by some state-supported bishops”, he says.

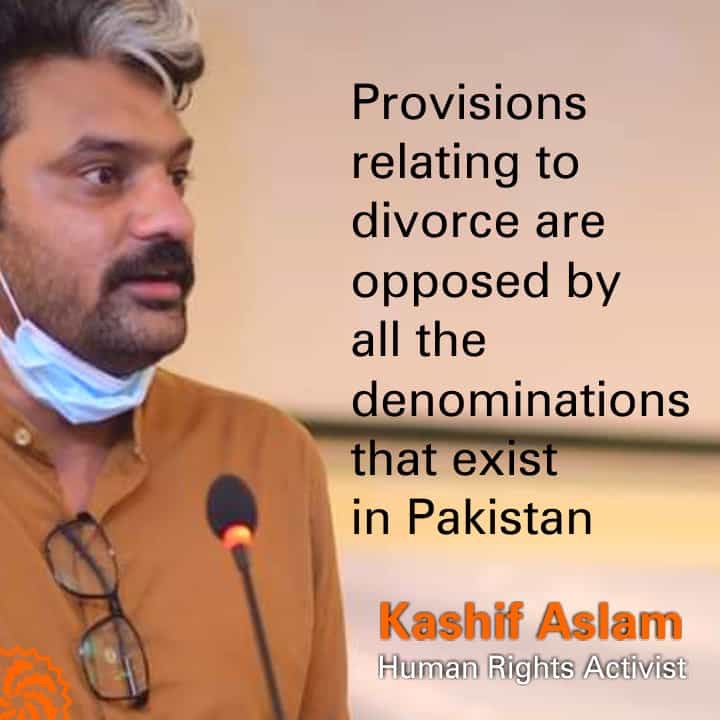

Whatever the reality, the fact is that Section 7 was removed without a broad-based consultation with Christian community. It is also a fact that no Christian leader opposed its removal at that time. “A large majority of Christians living in Pakistan did not even know what had been taken away from them,” says Kashif Aslam, a Christian rights activist, as he explains the reasons for this silence.

The removal of the section first became a public issue after Benazir Bhutto had become prime minister in 1988. “A debate on women’s rights ensued in Pakistan during her tenure because her government had signed the Convention for Eradicating Discrimination Against Women (or Cedaw),” Asalm says.

Pakistan was bound by the convention -- which was a global commitment made by many countries under the auspices of the United Nations -- to improve living conditions for Pakistani women. “Some Christian community leaders also started raising their voices in those days against the injustice inflicted upon their community by the Zia regime,” he says.

Consequently, Benazir Bhutto’s law ministry tried to draft a law that could help Christian women to get divorce without having to satisfy the terms and conditions of Canon Code. “This attempt fizzled out after it was opposed by Christian clergy,” he adds.

The debate about Section 7 was re-initiated around three decades later when Justice Mansoor Ali Shah ruled as a judge of the Lahore High Court in 2017 that its removal was unconstitutional. He arrived at this conclusion after hearing a petition filed by one Ameen Masih.

The petitioner had pleaded that he and his wife wanted to part ways but did not want to accuse each other of committing adultery – one of the basic grounds for separation of Christian couples under Canon Code.

Shah’s decision was challenged by some clergymen in front of a larger bench of the Lahore High Court where it is still pending hearing. As Asalm puts it: “There were strong voices of opposition to the judgment. Its opponents argued that the revival of Section 7 would make divorces rampant in Christian community.”

One way of putting an end to this controversy is that parliament annuls Ziaul Haq’s presidential ordinance which, after all, was issued by a dictatorial regime. The PTI government is avoiding that route.

And, in doing so, it is relying on the same reason that Zaiul Haq had used for removing Section 7 in the first place. “Its revival means that the English civil law will be applied to Pakistani Christian families,” says a PTI legislator without wanting to be identified by name. “How can the Pakistani state allow a foreign law to operate within its own jurisdiction?”

Too many cooks spoiling the broth

The Christian Divorce Act in its current shape allows a Christian couple to leave each other only if one of them can prove that the other is committing adultery. While it is almost impossible for mostly illiterate and poor Christian women in Pakistan to prove in courts of law that their men are committing adultery, they also do not want to be publicly accused of being adulterous because the allegation can ruin their social and family life forever.

In the absence of any alternative, says Ruth, many women are being forced to change their religion because a Christian marriage is annulled automatically if one of the spouses converts to another religion.

This, according to her, explains why the condition of adultery for a divorce is abhorred by everyone in Christian community. “It inflicts severe hardships upon Christian women,” she says. “There is also a widespread awareness among Pakistani Christians that this condition has to be changed, that space has to be created for the annulment of incompatible marriages on some other grounds as well,” she says.

The problem is how to do that because many efforts in this regard have already floundered.

One of these efforts was made by Ruth herself. As a member of Punjab Assembly between 2013 and 2018, she says she “tabled a draft law but the then provincial government turned it down”.

Around the same time, according to Aslam, Catholic Church of Pakistan, which has the largest following among Pakistani Christians, also made an attempt to introduce amendments to the Christian Divorce Act. “It organized an assembly of Catholic churches in 2016,” he says.

Held under the banner of National commission for Justice and Peace, a church-affiliated human rights organization, and attended by the heads of 12 Christian denominations, the assembly continued for two months in Lahore. After thorough discussions, its participants finally agreed to create provisions for a divorce.

“The assembly then drafted a law from a human rights perspective,” says Aslam who was one of its organizers. The draft purported to make several amendments in Christian family laws – including the ones that made it easy for Christian couples to divorce each other.

In turn, the draft was handed over to Senator Kamran Michael who was then a federal minister in the government of Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN). The internal differences of Christian community, however, did not allow him to present it to parliament.

Conservative Church leaders were opposing the draft because it gave the right of divorce to human beings thereby changing Christian marriage from a sacred union to a civil partnership. Civil society organizations were not happy with it because it did not give Christian women an all-encompassing right to divorce – just like what women in Christian-majority countries of Europe and North America have.

Aslam points out that the opposition to divorce is not restricted to just Catholic Church. “It is common to all the denominations that exist in Pakistan,” he says.

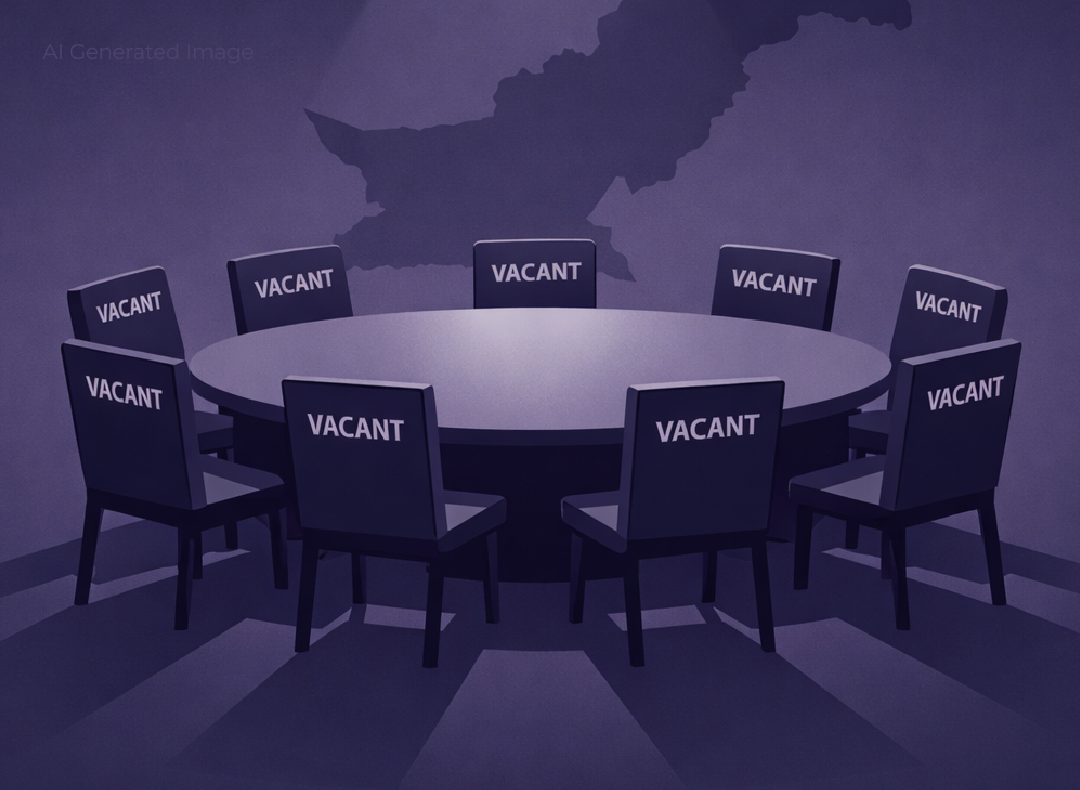

These denominations, or sects, are, indeed, the biggest hurdle in the new law’s passage – mainly because they are too many. There are 238 different denominations among Pakistani Christians, says Aslam. “This makes the process of arriving at a consensus on amendments in divorce law very difficult,” he says. “In fact, there can never be a consensus in the community over anything.”

This disunity is one of the major reasons why negotiations between the PTI government and Christian community leaders failed after August 2019. The government side was represented in these negotiations by Shireen Mazari and parliamentary secretary for law Maleeka Bokhari. The Christian community’s representatives included the nominees of all the major denominations as well as the members of many civil society organizations.

It took only a lone representative of a lone religious group to thwart a positive outcome of the talks, says an official of the federal human rights ministry. And, as a result, the passage of a reformed Christian Divorce Act has been delayed indefinitely.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 24 May 2021, on its old website.

Published on 10 Jun 2022