If you pass through the narrow streets of Ranchor Line in Karachi and reach Hardas Street, you can find the office of the Gujarati Bachao Tehreek (Kathiawar Mansoori Jamaat). It has shop-like shutters with a large banner displayed on it, which reads ‘Free Gujarati Class’ in both Urdu and Gujarati scripts.

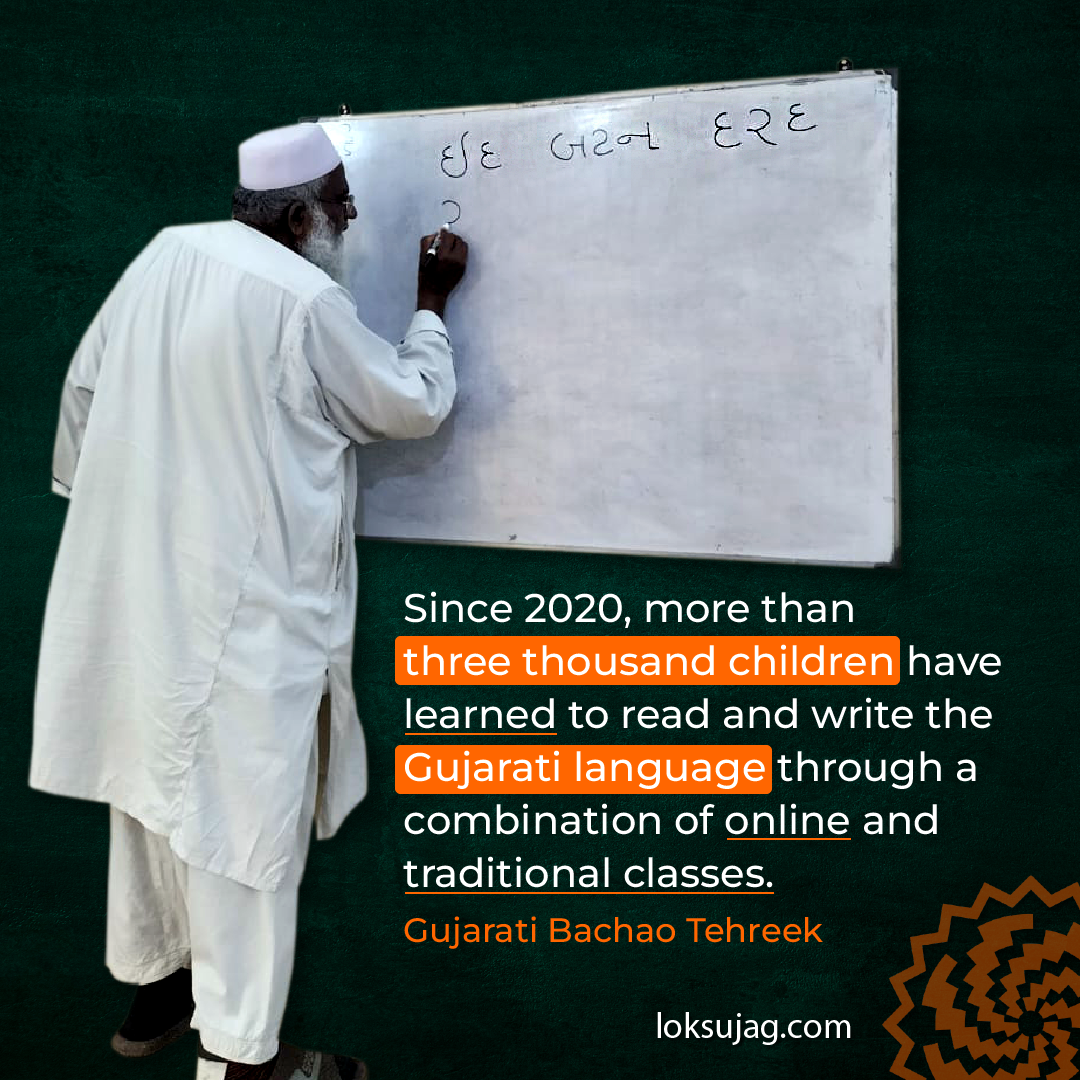

Sixty-five-year-old Muhammad Younis is teaching Gujarati to three students in the office which looks like a hall. He writes Gujarati alphabets on one side of the white board and Urdu alphabets on the other side, which the children note down while pronouncing them.

Muhammad Younis is a teacher by profession, residing in the Ibrahim Hyderi area of Karachi. Every Sunday, he comes to Ranchor Line to teach children Gujarati for free while he also gives free coaching of his mother tongue (Gujarati) in other parts of the city. He is concerned that the Gujarati language in Pakistan is on the verge of extinction. He has fears that if this language disappears, the cultural traditions of his community will also fade away.

“The community has started free classes to teach children Gujarati language and its script so that its mother tongue can be preserved. For this purpose, I have also prepared a Gujarati language primer on the self-help basis,” says Younis.

Gujarati language once dominated Karachi

Gujarati was once a very important language in Karachi and the Gujarati people are considered among the founders of modern Karachi as they were the frontrunners of business class.

Three newspapers from Karachi—Millat, Vatan, and Dawn—used to be published in Gujarati. Ten printing presses printed Gujarati magazines and books while newspapers and literature were also imported from India.

Bawa Hyder Khoja, the secretary information of the Gujarati Bachao Movement, says the Gujaratis had started settling in Karachi more than 200 years ago. By the time of Pakistan's creation, the Gujaratis, Baloch, Sindhi, Parsis and Christians all these communities spoke Gujarati.

“If you look at old pictures, you can see Gujarati script on Jewish synagogues. The Quran, the Bible, and the religious books of Parsis, as well as romantic literature, poetry, and Communist literature, were all available in Gujarati language.”

Mr Khoja says that until the Partition of India, there were four Gujarati-medium schools in Karachi, while two Sindhi-medium school principals were from the Gujarati community. Gujarati was an optional subject in the curriculum until 1971 and tax returns were filed in Gujarati language until 1974.

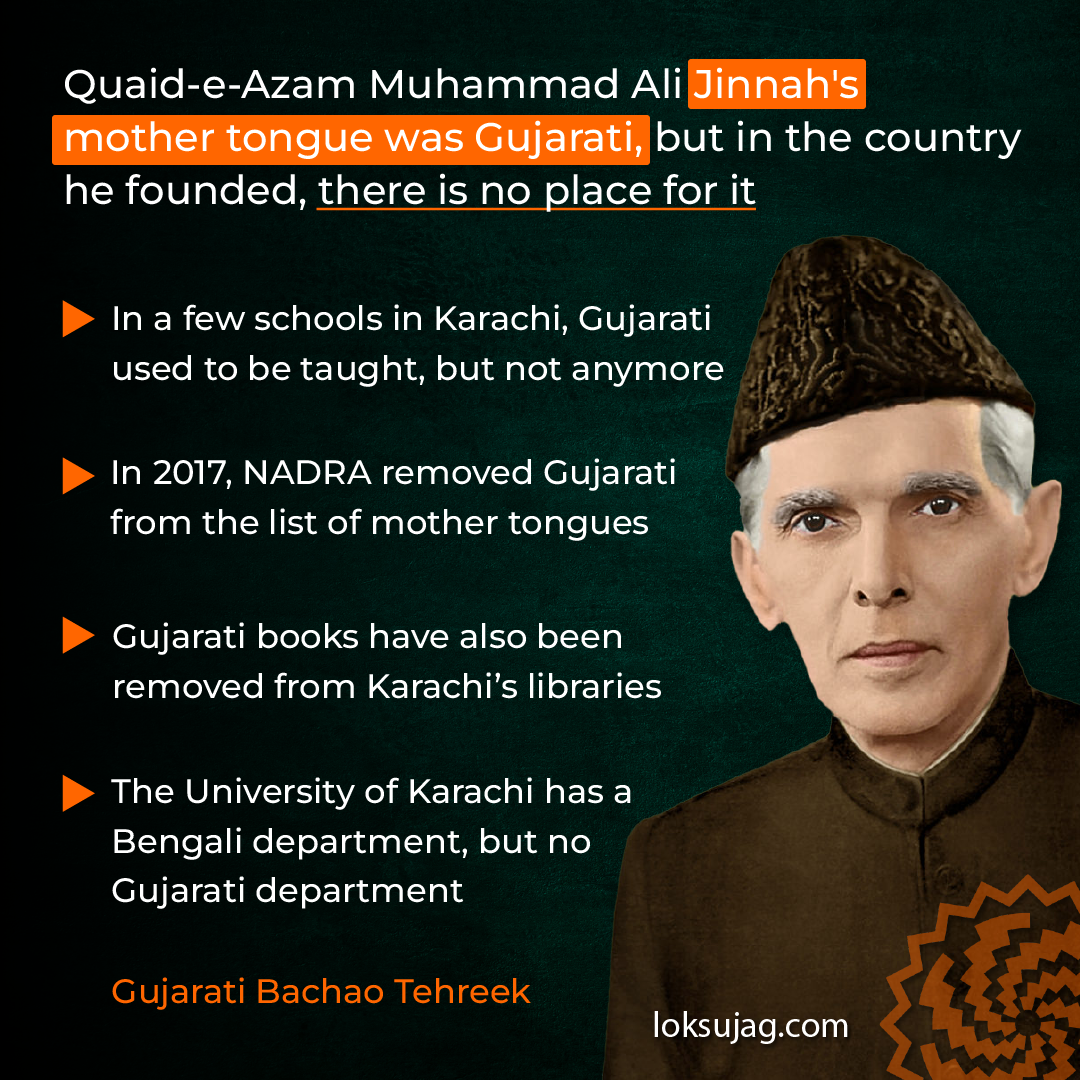

Quaid-i-Azam’s mother tongue has no place in Pakistan

Bawa Hyder Khoja, who has online taxi business, says that Gujaratis started leaving their mother tongue gradually and adopted the market language, i.e. Urdu, and business while political matters further complicated things. Now only three or four printing presses and two newspapers are left that are published in Gujarati.

“The formation of the One Unit and the discouragement of regional languages had a very negative impact on Gujarati. The community leaders of that time prioritised their businesses and Urdu over resistance, which has caused us significant loss.”

Mr Khoja says that Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah himself was a Gujarati but the country founded by him had no space for his mother tongue at the official level while the community’s connection with its language also weakened. In fact, NADRA (National Database & Registration Authority) removed Gujarati from the option of mother languages in identification forms in 2017.

“Now, when we ask children to learn Gujarati, they ask, ‘Why should we learn it if it’s not needed?’ But for us, it’s an emotional matter.”

Another leader of the movement, Muhammad Anwar, says the decade from 1974 to 1984 was very harsh for the Gujarati language in Karachi. The Bohra, Parsi, Memon, Hindu communities, and others all speak Gujarati but very few know how to read and write it.

According to Bawa Haider, in resistance to the unfair treatment meted out to the Gujarati language, the community started the Gujarati Bachao Tehreek in 2019 to launch the struggle for the restoration of the language and culture.

How many people speak Gujarati?:

Globally, more than 60m people speak Gujarati and about 55m of them live in India. It is the sixth most spoken language in India and is also the official language of the state of Gujarat.

Azam Ghanchi, president of the All Pakistan Gujarati Federation, says that the population of Gujarati speakers in Pakistan is around 3.5m and most of them live in Karachi.

“Among the Gujaratis in Pakistan, there are Khoja Ismaili, Khoja Shia, Khoja Sunni, Memon, Ghanchi, Kathiawari, Junagadhi, Kutchhi, Momina Ismaili, Momina Shia, Momina Sunni, Sipahi, Cheepa, Parsi, Gujarati Hindus and other communities. But our language is gradually becoming extinct.”

Gujarati is a rich language from the point of view of literature, culture, art, poetry and science, and has a great potential to keep pace with the digital world.

In India, the language has its own AI models, AI voice generator algorithms, speech recognition models, speech analytics models, smart assistants, and ChatBots. However, in Pakistan, there is a lack of digital content while very few people can read and write Gujarati.

Hope as 3,000 children learned Gujarati in five years

The leaders of the Gujarati Bachao Movement complain that even Gujarati books have been removed from Karachi’s libraries, including the Quaid-i-Azam Residency Library. While the University of Karachi has a Bengali department, no work has been done for the Gujarati language. They say that the Ayesha Bawani School, built by the Gujarati Memons, does not teach Gujarati. The situation is so bad that there are now no more Gujarati teachers. Despite all this, political leaders of the Gujarati community have opted to remain silent.

Muhammad Younis realises the absence of an Urdu-Gujarati dictionary. He is compiling a dictionary by hand. But due to the lack of resources or help from the youth for use of technology, the process of compilation would take time.

The leaders of the Gujarati Bachao Movement claim that as a result of their efforts, more than 3,000 children have learned to read and write Gujarati through online and traditional classes since 2020.

While teaching the children, Muhammad Younis says that he is not discouraged and to meet their educational needs of children, he is preparing books in the mother tongue and even writing tableaux.

Issue of Gujarati script’s similarity to Devanagari

Gujarati’s script is similar to the Hindi script (Devanagari). Most of the languages in India, which are written in similar scripts, belong to the same family. The Bengali script also belongs to this family and the script used for Sikh Punjabi (Gurmukhi) is also from the same group.

In the subcontinent, the relationship between script and religious identity has become very deep. Urdu, Sindhi and Pashto are written in scripts belonging to the Arabic and Persian family. Some linguists believe Gujarati language is facing issues in Pakistan due to its script. There are very few people in Pakistan who can read and write it.

Muhammad Younis says the Hindu followers are more interested in learning the Gujarati script because their religious books are in Devanagari script. The Aga Khani community also needs the Gujarati language.

Kishor Kumar brought his children to learn Gujarati at the movement’s office: He says that young Hindus are working for the Gujarati language in many areas of Karachi and they even teach Gujarati for free.

Hindu community organizations like The Education Sanstha (TES), All Karachi Kathiyawari Hindu Samaj, Shri Swaminarayan Mandir and Khoja (Pirhai) Shia Isna Asheri Jamaat in Karachi are teaching Gujarati to their members through online as well as free in-person classes.

Can Gujarati cinema save language?

The Gujarati Bachao Movement is introducing the community to Gujarati films made in India. Azam Ghanchi say that after the movement’s efforts on social media, Gujarati filmmakers and distributors have contacted them though there has been no significant progress yet. The movement’s leaders remain hopeful that work will go on at the community level although its pace is slow. Cultural events are held here, Khoja Jamaat organises Gujarati mushaira in Muharram while two Gujarati libraries will soon be opened.

The Gujarati movement leaders say that they are trying to save their mother tongue by contacting the leaders of different political parties, but so far, they haven’t achieved any success. They demand that the government take steps for the restoration of the Gujarati language through consultation and action.

Published on 24 Feb 2025