The relationship between the Pakistani state and the linguistic identity of its people has been antagonistic since independence. The ill-advised attempt to make Urdu the official language of Bengal in the early months of independence is enough to understand how negative this relationship has been.

The ruling elite of Pakistan has considered linguistic diversity a hurdle to the concept of one nation and it denied the existence of this diversity of sought to erase it through suppression.

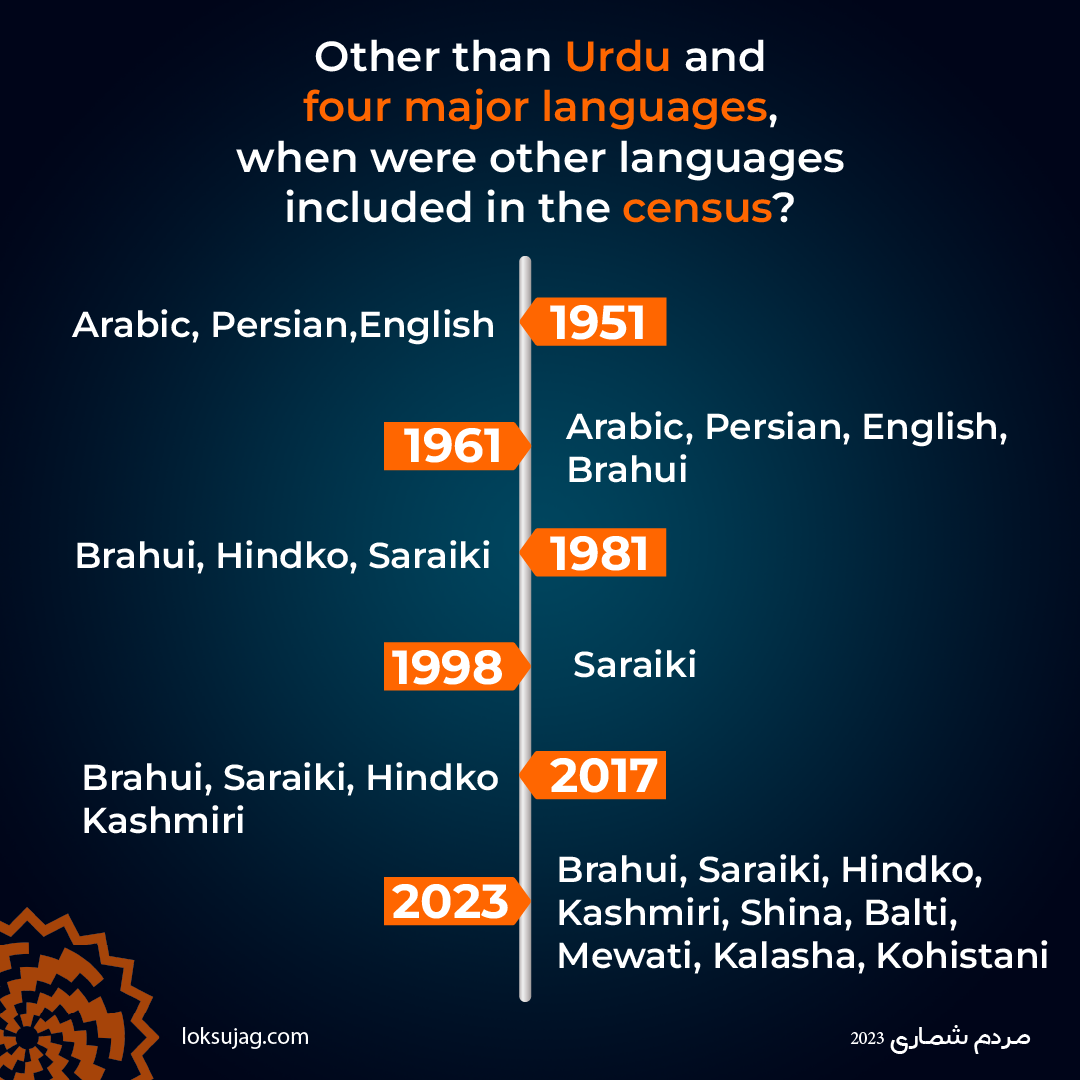

In the 1951 census, although the section for mother tongue had been there being the legacy of the British rule, the linguistic diversity within the provinces was not taken into account, except for Urdu. By 1961, provinces were abolished due to ‘One-Unit Scheme’ in West Pakistan, but Brahui was granted the status of a separate language in Balochistan. In the third census held in 1972, though provinces were restored, the section for languages was completely eliminated.

In the 1981 census, not only was the counting of mother tongues reinstated Brahui in Balochistan, Hindko in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Seraiki in Punjab were give the status of separate languages. The next census, conducted with a seven years delay in 1998, excluded the Brahui and Hindko from the section of mother tongue.

In 2017, all previous languages were once again accommodated in the form, with the addition of Kashmiri. In the 2023 census, languages like Balti, Shina, Kalasha, Kohistani, and Mewati were also added to the section for mother tongue.

The odd inclusion or exclusion of languages in the census form suggests that these decisions were made under temporary pressure or political expediency but not under any systematic and principled policy. For this reason, the data from the censuses does not authentically convey the full story of the linguistic identity of various communities but it does reveal some aspects.

Some of these aspects are given below:

1- The largest new linguistic identity is Seraiki

In 1981, when Seraiki was first included in the census, those who identified Seraiki as their mother tongue constituted 14.9pc of the total population of Punjab, which has now increased to 20.6pc.

One reason for this increase is the higher birth rate in Seraiki belt. However, the birth rate is not the only reason. Some people from southern Punjab regions joined the Seraiki identity later on. For example, in 1998, 74pc of the population of Mianwali identified their mother tongue as Punjabi but in the next census (2017), the same percentage identified it as Seraiki. This trend continued in 2023.

Seraiki

2017 کی مردم شماری کے نتائج: پنجاب میں سرائیکی بولنے والوں کے تناسب میں اضافہ۔

This change was also witnessed in districts like Vehari where three-fourths of the population spoke Punjabi. Between two censuses, the number of people identifying Punjabi as their mother tongue decreased by 8pc while the number of people identifying Seraiki increased by the same amount. However, this trend did not appear in some other districts of south Punjab, such as Bahawalnagar.

2- Punjabi speakers are no longer the majority in Pakistan

In 1951, the combined population of Punjab and the Bahawalpur state was more than 20 million, and the number of Punjabi speakers in the country was also counted as the same. The total population of West Pakistan was 33.7 million. However, in 1981, when Seraiki speakers were counted separately, the percentage of Punjabis in Punjab decreased to 79pc, and it further dropped to 67pc by 2023. This means that now, for every three residents of Punjab, two speak Punjabi as their mother tongue and one speaks Seraiki or some language.

Punjabi

The state of Punjabi language at educational institutes

The numbers also show that in 1951, Punjabi speakers constituted 62pc of the total population of West Pakistan, a clear majority. However, due to later linguistic division and a relatively lower birth rate among other linguistic groups, the share of Punjabi speakers in the total population of Pakistan decreased to 37pc by now.

3- Punjabis are abandoning their language

It is not new for the urban elite of Punjab to identify as Urdu-speaking but this trend showed a significant increase in the last two censuses, conducted five years apart.

In 2017, the percentage of Urdu speakers in Punjab was 4.87pc. If this percentage remained the same in 2023, their total population in Punjab should have been around 6.2 million. However, the number of people in Punjab who identified Urdu as their mother tongue in the 2023 census was recorded at 9.14 million. It is safe to say that in these five years, 2.5 to 3 million people in Punjab preferred to write Urdu as their mother tongue instead of Punjabi.

پنجابی

لسانی ہجرت 2023: پنجابی اپنی ماں بولی کو گھروں سے نکال رہے ہیں

Among those who “linguistically migrated,” at least one-third are from the Lahore district. The estimated number in this district is around 1.1 million. This means that every tenth person in the district changed their mother tongue between 2017 and 2023.

4- Pashto speakers are spread across all four provinces

Pashto-speaking people are Pakistan’s second-largest linguistic group. In 1981, 140 out of every 1,000 people in Pakistan spoke Pashto as their mother tongue and now the figure is 181. One reason for this increase is the higher birth rate among the Pashtuns, but other factors are the better access to remote areas which improved the counting in the census and migration from Afghanistan.

Another important feature of Pashto speakers is their widespread presence across Pakistan. Pashtuns are the only linguistic group present in significant numbers in every province of the country. For comparison, 97pc of Punjabi speakers live in Punjab and the same is the case with Sindhi speakers but three-fourths (75pc) of Pashtuns live in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa while the rest (25pc) are spread across other provinces.

Pashto

Platforms to launch Pashto into digital space and AI

Until 1981, 95 percent of Pashtuns either lived in the present Khyber Pakhtunkhwa or in the northern districts of Balochistan, which are their native homeland, but in the next four decades, the proportion of Pashtuns in these areas decreased by eight percent, and it increased by the same in Sindh and Punjab, meaning Pashtuns migrated from their areas and settled in these provinces.

5- Karachi, Sindh, is home to every linguistic group in Pakistan

Sindhi speakers constitute 60pc of the population of Sindh. The largest population of Urdu speakers in the country also resides in Sindh, making up 22pc of the population of the province.

From a distribution perspective, Sindhi speakers are unlike Pashtuns. According to the 2023 census, only three out of every 100 Sindhi speakers live outside of Sindh, with half of them residing in Balochistan, which is their ancestral region

Sindhi

How is Sindhi language faring in digital world ?

For comparison, see that 13pc of Pashtuns now live in Sindh and Punjab, outside their ancestral regions in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan.

The capital of Sindh, Karachi, is home to every linguistic group in Pakistan. It is the largest city for Pashto, Balochi, Urdu, and Balti speakers.

6- The ‘Other’ language category is expanding

In the first census in 1951, 985 out of every 1,000 people in (West) Pakistan spoke one of the five major languages (Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto, Balochi, or Urdu). Only 15 people spoke a language that did not fit into these categories, so they were placed in the ‘Other’ category.

Pashto

Lok Sujag review, teaching of five mother languages in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa schools

The number increased to 179 in 2023. Of these, 165 had their languages recognized in new categories such as Seraiki, Hindko, Balochi, Mewati, Shina, Balti, Kashmiri, Kalasha, and Kohistani. However, 14 out of every 1,000 people still consider their mother tongue to be outside the available categories and are striving at some level to get it recognised as a separate language.

Gujrati

What happened to Gujarati language that once ruled Karachi?

Gujarati was once a highly significant language in Karachi, and Gujaratis are considered among the founders of modern Karachi. They belong to the forefront of the business community.

Hazaragi

Hazaragi speakers resist Persian label for their language

In Quetta city, the majority of people speak Balochi and Pashto, but the areas of Hazara Town and Mariabad are considered the "homeland of the Hazara community." They are distinguished by their Mongolian facial features and can be easily recognized in a crowd. The largest Hazara community population in Pakistan resides in Quetta.

Mewati

How did Mewati get the status of separate language in Pakistan?

India's 2011 census recorded the total number of Mevati speakers as 856,643, while Pakistan's latest census (2023) reported their population as 1,094,219. This suggests that even today, the Meo community remains almost equally divided between the two countries.

Published on 6 Mar 2025