Nusrat Hussain Tofan boasts a 48-year career in journalism in Charsadda. Over the years, he has been affiliated with numerous prominent national and regional newspapers, and his experience extends to collaborating with three distinct news channels.

He emphasises that journalism organisations neglect to provide salaries to their representatives at the district level and impose a significant financial burden on them under the guise of security, a sum often left unreimbursed upon their departure from the institution.

“All journalism organisations, whether print or broadcast, consider regional reporters merely as conduits for news coverage. They show little concern for anything beyond that; my experience with them has been profoundly disappointing.”

He says he has dedicated his life to journalism and public service, leaving him reluctant to explore other avenues.

Like the rest of the country, in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, hundreds of journalists, including reporters, sub-editors, assignment editors, camerapersons and photographers, contribute to newspapers and TV channels. Many of them struggle to secure the government-mandated minimum wages.

Most journalists face deprivation of the salaries stipulated by the Wage Board Award, leading to a life of poverty.

The federal government has declared wage awards for journalists’ salaries on eight occasions in the last 50 years, yet these announcements have not been implemented to date.

The Newspaper Employees (Condition of Service) Act of 1973 established a ‘Wage Board’ to determine the wages of newspaper employees. The government appoints a retired judge of the High Court or an individual of equivalent rank as its chairman.

The Wage Board comprises an equal number of representatives from newspaper owners and working journalists (unions). Considering the inflation rate, this body determines the salaries and additional benefits of newspaper employees. The salary formula is established based on the grades or ranks of media employees.

The inaugural wage board for working journalists was established in 1960 under the ‘Conditions of Service Ordinance.’ It proclaimed the Wage Award on December 31, 1960.

However, it faced a 13-year delay in implementation, allegedly to avoid the displeasure of newspaper owners. In 2008, a new ‘Conditions of Services’ law was enacted, though not entirely enforced. Despite this, wage awards persisted every five years until 1994.

In July 2000, when the seventh Wage Board Award was declared, media owners, including the newly established private channels, refused to accept it.

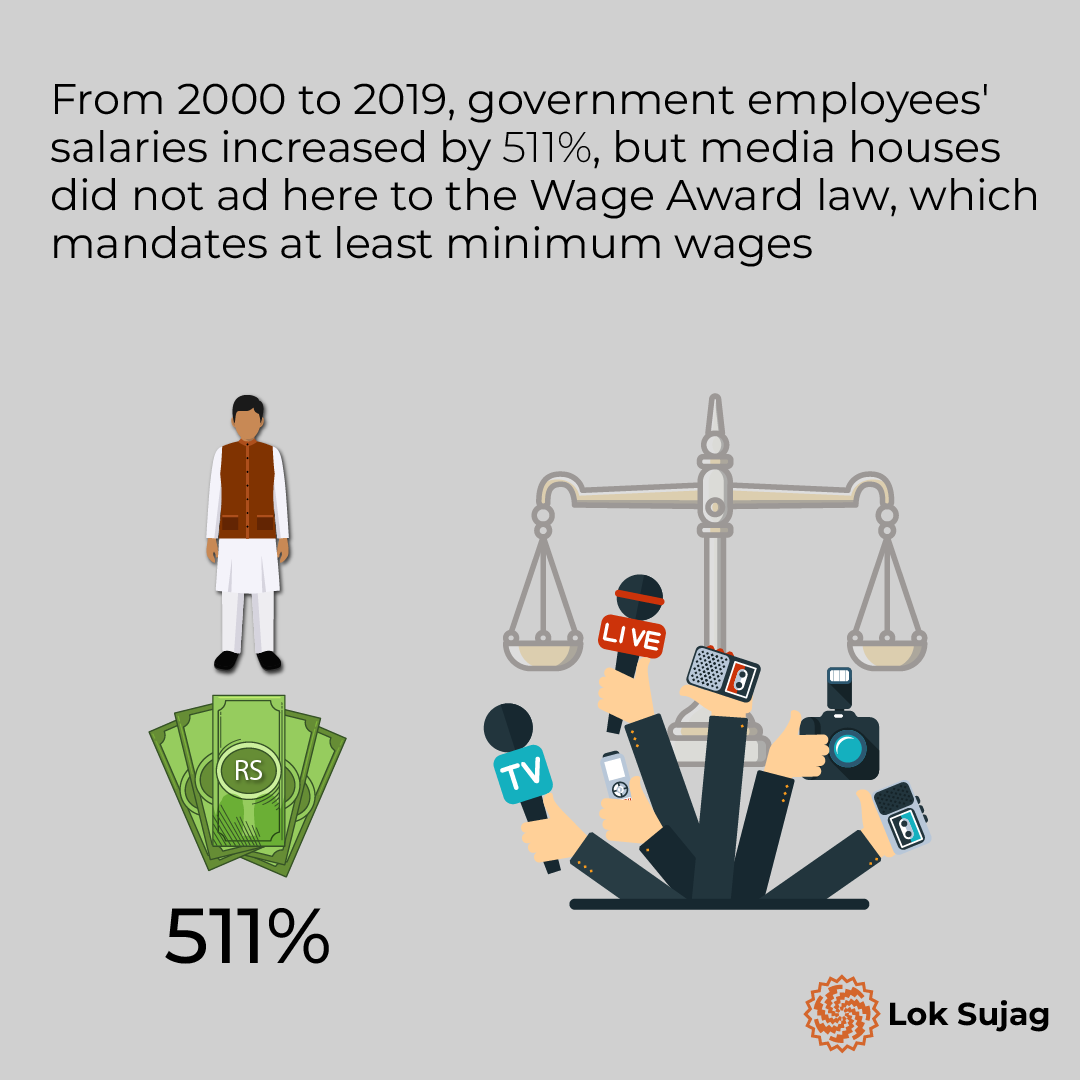

During this time, salaries in public and private sectors experienced a surge of 400 to 500 per cent. However, the wages of journalists, fixed six years ago, have remained unchanged.

Simultaneously, media houses initiated the retrenchment of workers, prompting employees and journalists to launch a movement advocating for the implementation of the wage award.

The government of Pervez Musharraf attempted to enforce the award, but it ultimately had to yield to the pressure from media owners.

Simultaneously, the All Pakistan Newspapers Society (APNS), an organisation representing media owners, contested the seventh wage award in the Supreme Court, arguing that the Newspaper Employees (Conditions of Service) Act of 1973 was a discriminatory law aimed at suppressing journalistic freedom.

Although laws akin to the Wage Board Award have been in practice for years in Bangladesh and India, legal proceedings had commenced in Pakistan.

It took four years for the court to dismiss the APNS petition. Simultaneously, the petitioner was informed that they could approach a ‘court of competent jurisdiction’ if they wished.

This decision did not alleviate the difficulties of journalists. Media owners took the case to the Sindh High Court, where the changing bench delayed five more years before a decision was reached.

In August 2009, the Supreme Court issued a directive for the case to be decided within 90 days, but the Sindh High Court did not adhere to this timeline.

In September 2010, the High Court reserved its decision, but it was not announced until 2011.

Consequently, journalists had to appeal to the Supreme Court.

Due to the media owners’ request, journalists were compelled to work with the salaries determined by the owners. In 2018, the controversy over the appointment of the chairman began with the announcement of the eighth Wage Award.

Thus, from 2000 to 2019, the salaries of government employees increased by 511 per cent, while media houses, aside from the wage award, did not adhere to the minimum wage law.

The situation has remained the same until now.

Thirty-six-year-old journalist Safeer Ahmed, a resident of Chitral, is associated with a private TV channel in Peshawar as a copy editor. He started his journalism career in 2007 with Radio Pakistan after completing his Master’s in Mass Communication from Peshawar University.

Safeer Ahmed served as a sub-editor for eight years at the daily Dopehar in Islamabad and later at the daily Mashriq in Peshawar. Despite supporting five family members, he receives a salary from the institution that falls below the minimum monthly wage set for labourers.

According to him, receiving a salary or benefits from the organisation, as per the Wage Board award, seems like a distant prospect. He says he is unaware of the grade in which he is classified.

“I wouldn’t hesitate for a moment to bid farewell to journalism if presented with a better job opportunity. It’s preferable to leave a profession lacking job security and fair remuneration, where human rights advocates cannot even ask for their own rights.”

Senior journalist and former president of the Khyber Union of Journalists, Saiful Islam Safi, asserts that the eighth wage award provided temporary relief of five thousand to eight and a half thousand rupees for media workers.

Nevertheless, only a handful of workers in two or three national newspapers have seen these recommendations implemented.

“This Wage Board Award exclusively applies to the print media and does not include journalists from the electronic media.”

To enforce the wage awards, the Implementation Tribunal of Newspaper Employees (ITNE) was established under the Newspaper Employees (Conditions of Service) Act 1973, with its headquarters in Islamabad.

This tribunal allows individuals affiliated with newspaper organisations to file complaints if they do not receive salaries per the wage awards.

The Chairman of ITNE reviews the applications and possesses the authority to enforce the decision using the Revenue Act.

Saiful Islam Safi highlighted significant issues in the implementation process. Firstly, dozens of cases have been pending in ITNE for an extended period. Secondly, a newspaper worker cannot file an application in ITNE against any organisation without their appointment letter.

“In other words, you are not considered an institution employee without an appointment letter. Your claim against it does not stand. Therefore, many journalistic organisations do not issue appointment letters to correspondents working in their offices or districts. The letters we receive are from alternative companies they created but do not bear the institution’s name.”

Nasir Hussain, the president of the Khyber Union of Journalists, an organisation representing journalists in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, asserts that the twelfth wage award should have already been announced. “It has been four years since the last wage award, and there has been silence since then.”

“After four years, little attention has been paid to rising inflation. In terms of award implementation, only a handful—about five or six individuals—from three newspapers (Daily Jang, Daily The News, and Daily Dawn) among the 600 members of the Khyber Union are receiving wages in accordance with the Wage Board.”

Also Read

Plight of journalists in Balochistan: Unpaid wages and precarious working conditions

He notes that with the new PEMRA Amendment Act, the Council of Complaints will be instituted in Islamabad and provincial capitals, providing electronic media workers with a platform to file complaints about delayed or non-payment of salaries.

“When the income of media workers is not on par with that of a daily labourer, salaries are disbursed sluggishly, and numerous months of dues remain outstanding. In such a scenario, the nominal declaration of the wage award proves futile; it demands effective implementation.”

Rahatullah Khan, Associate Member of APNS and Editor-in-Chief of the daily Aeen Peshawar, says that newspapers’ revenue relies on advertisements and business. “Larger organisations can afford to pay wages as per the Wage Board, but it poses challenges for smaller newspapers.”

He says that the government is not expeditiously supporting workers’ salaries. Government advertising cheques are received months later, intended for previous expenses.

“Consequently, they have to pay workers from their own pockets.”

Fazlul Huq, Editor-in-Chief of the Daily Times Peshawar, remarks that the current situation is dire. With few advertisements and negligible circulation, implementing the Wage Board salary recommendations becomes challenging.

“Regional representatives receive a 50 per cent commission on advertisements, and we consider this part of their salary because we cannot pay them fully.”

Lok Sujag sought information from the provincial labour department under the RTI Act regarding Wage Board awards or minimum wages. However, they evaded the request, stating, ‘It’s a federal matter,’ while the federal secretary of labour has yet to respond to the RTI application.”

“The Information Department of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa acquitted itself by suggesting approaching the Khyber Union of Journalists and Peshawar Press Club in response to an RTI application, while the Press Information Department (PID) has not bothered to reply despite the passage of a month.”

Published on 15 Dec 2023