Muneeza Manzoor Butt is working as the manager of Multan’s Violence Against Women Centre (VAWC). This is not her original job because she was posted here as a senior psychologist – a position that she still holds simultaneously. She has a third job as well – of a women protection officer for district Multan.

As a consequence of her multiple assignments, the centre neither has a full time manager nor a full time senior psychologist. At least six other major posts here are also lying vacant.

Hiba Akbar, a Lahore-based lawyer, found out something similar in her research on the centre’s efficacy. She says it did not have any in-house doctor over many months during 2021 and it still does not have a radiologist to run its x-ray facility. Similarly, its pathological laboratory does not have any staff. So, even the most basic blood tests cannot be conducted here.

On a February 2021 day, the only person present in this laboratory is a doctor. He has been assigned the task of issuing medicolegal certificates to the victims who approach the center. He, however, is not its employee and has been posted here temporarily by the district health authorities.

The women victims of violence arriving at the centre, therefore, are sent to Multan’s largest public healthcare facility, Nishtar Hospital, even for such minor procedures as getting an x-ray. This involves travelling another 13 kilometres or so – something that many victims might not be able to do due to the state of their health or because of the threats to their safety.

Unkept promises

Punjab Assembly passed the Women Protection Act in 2016. Among other things, that law provided for the setting up of Violence Against Women Centres (VAWCs) in different parts of Punjab.

These centres are meant to provide solutions to the women victims of various kinds of violence for all their legal, judicial, medical and psychological grievances under one roof. Each one of them, therefore, is supposed to include a police station entirely staffed by women, a pool of lawyers, prosecutors, a court, doctors, medical laboratories, psychological counselling facilities and a shelter for the victims who cannot go back to their families.

The Punjab government initially decided to set up three such centres – one each in southern, central and northern parts of the province. So far, however, only one of them has come into being in Multan.

Built with 232 million rupees in 2016-17, it is located just off Matti Tall Road, next to the Women University in the northern outskirts of the city. A couple of advertising posters point to it from the main road.

Its huge wrought iron gate is well guarded. Visitors have to record their reasons for entering its premises in a register kept in a tin shed erected by the entrance. The guards also don’t allow any mobile phones or cameras inside due to what they call “security” reasons.

The gate opens onto a large, manicured lawn, lined by three impressive multi-floor building blocks standing side by side in a semi-circle. The frosted glass doors of one of the building opens into a polished hallway which has a large front desk. ‘Now you are safe’ – VAWC’s motto – is etched above that desk in large letters.

The entire premises of the centre are watched by 75 close circuit cameras. All the conversations taking place at its front desk are also duly recorded with strategically placed microphones. Its architectural grandeur and its sophisticated technical equipment, however, do little to hide the fact that it is doing almost nothing.

Butt says the reason for this inactivity is that the centre does not have sufficient funds. Consequently, she says, even the 37 employees it has hired so far did not get paid regularly till recently.

The initial reason for the unavailability of money, according to her, was that the provincial government could not immediately set up the Women Protection Authority mandated to oversee the centre’s working. After the authority was finally set up in 2019, she says she spoke to its chairperson Fatima Chadhar who has assured her that the salaries of the VAWC’s existing staff would be paid regularly.

Consequently, she says, “these staff members have been given a nine-month contract”.

This state of affairs irks Salman Sufi, a policy expert who was a part of the Punjab government’s team that launched VAWC. “If you take away the funds, stop filling the posts and don’t pay the staff, how is the centre going to show results,” he says.

He also claims that it was built and made functional in 2017-18 only because the then Punjab Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif “took personal interest in its affairs”. But this interest is absent now, he says.

This absence, according to him, explains why the provincial government has failed to set up the next two centres over the last four years even though “we left behind 500 million rupees in 2018 for that purpose”.

The other reason for the lack of activity at the centre, according to Butt, is the lack of coordination among various government departments required to assist it in its working. Since the employees of these departments are answerable only to their own superiors, they do not take our referrals seriously, she complains.

This problem will persist until the Punjab government lays down rules and regulations to institutionalize coordination and collaboration between the centre and other government departments, she argues. Without that institutionalization, she says, all the commitments made by other departments remain verbal and, therefore, impossible to enforce.

Flaws in the system

The Multan VAWC does not yet have its in-house court yet. This means that women reaching it for the redressal of their complaints still have to go through the same old legal procedures that the centre was supposed to help them avoid.

Shazia Ayub, a Multan-based lawyer, highlights the importance of the in-house court by saying that the traditional legal system has been recognized by all and sundry as being unfriendly to women. To explain the problem with this judicial system, she cites a recent case in which a magistrate working in Multan dismissed a rape case in preliminary hearings, ruling that the victim seemed to have had consensual sex with the accused.

Butt concurs with Ayub.

The existing courts do not understand the nuances of gender-based violence and that was the reason why the center was supposed to have its dedicated judicial facility, she says. In the absence of that facility, she contends, “we have been limited to being a case registering body”.

The centre also does not have a shelter of its own to provide boarding and lodging facilities to the women victims of violence -- as was originally planned. “So, we send these women to Multan’s Daar-ul-Amaan,” says Butt, referring to a government-run shelter which houses women involved in all kinds of litigation. “So far, we have sent 59 women there,” she says.

Also Read

The deliberately silenced: What forces poor rape victims to take their allegations back

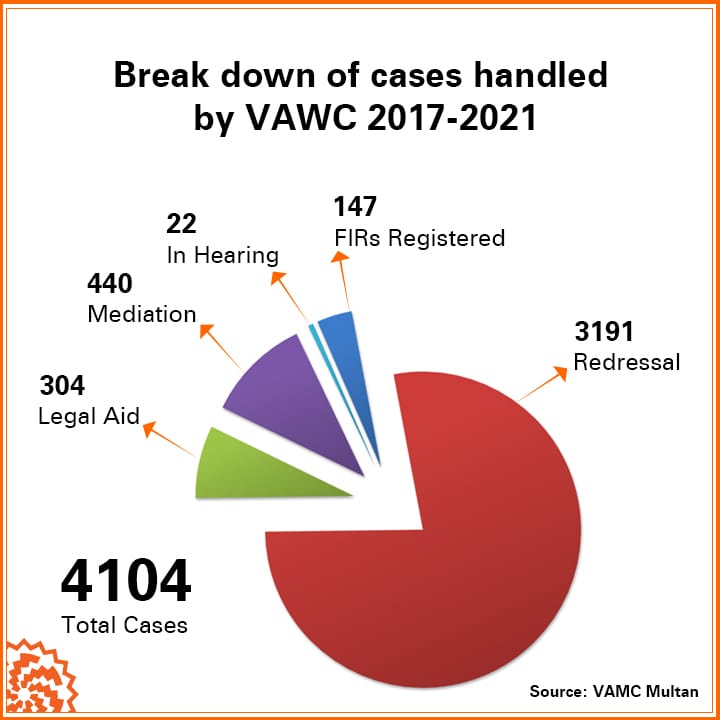

She, nevertheless, claims the centre has provided protection and rehabilitation to 4,333 women over the last three years. VAWC’s website, similarly, shows that it received 4,104 complaints by the end of 2021. Out of these, according to Butt, 3,191 have been addressed “either by referring them to other government departments for further action or by providing the victims with medical treatment, psychological help and financial assistance.”

What she does not talk about is the fact that only 147 of all the complaints that reached the centre so far have resulted in the registration of First Information Reports (FIRs) by the police posted inside it. These FIRs, too, have not all led to the constitution of cases because 26 of them have been quashed during investigation – including nine pertaining to the allegation of rape. In contrast, the complainants are said to have reconciled with the accused in as many as 483 cases.

A 2018 report prepared by the Punjab Commission on the Status of Women about the working of the center blames officers in charge of its police station for the registration of so few FIRs. It says they “closed” 725 complains in the very first year of the centre’s operations without taking any action. When they were asked to explain the reasons for that, the report states, their “answers were very vague”.

In other words, they are failing to address the very problem that they are meant to resolve: that existing male-dominated police stations do not take the complaints of violence against women seriously.

This flaw gets even more obvious when it comes to the number of cases being adjudicated and decided. According to the centre’s own data, court proceedings have started only in four cases it has referred to the judiciary in the last three years. The culprits have been convicted in just one of them.

Mukhtaran Mai, a rape-victim-turned-women-rights-activist, believes that such a low rate of adjudication and conviction has always been the main problem in stopping violence against women. The centre, she says, should have addressed this problem, not perpetuated it.

A resident of Muzaffargarh district situated next to Multan, she argues that most cases of domestic and sexual violence against women in these districts are not even reported to the police. “Many others are resolved through out of court settlements done under various kinds of social, political and economic pressures,” she says.

The centre, in her opinion, should have changed this situation for the better -- but it has not.

Published on 24 Mar 2022