When Chando Bheel, 55 year old resident of Sehri Dars village, was asked to give up his ancestral land and relocate to a “model” village a few miles away, he was naturally reluctant at first. But then the thought occurred to him that this was much larger than him — that he’d be doing his bit for the country. And that settled it.

“I left my ancestral land and home because I thought I’d be doing something for Pakistan,” explained Chando in a recent interview at his home in the New Sehri Dars village. The “model” village was built for the families of one of the villages displaced due to the coal-mining projects in Tharparkar.

And so, Chando moved to the New Sehri Dars Village, with hopes and dreams of a better future for himself, his family and Pakistan. But then, reality struck.

“We had agricultural land, crops and livestock was aplenty,” he reminisced. “But since we had to move, we sold it all off,” he said, the regret evident in his shaking voice. “Survival, here, is [now] hard.”

According to the Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC) — a joint venture corporation between the Government of Sindh and Engro Corporation founded in 2009 and tasked to mine and establish power projects from the Block II of the Thar coalfield in Tharparkar — the “solar-powered colony consists of 172 housing units, a school, a mosque, a temple and a market”. It was designed as a resettlement project for people displaced as a consequence of the of Thar Coal block-II, where coal mining has started. The new development was slated to be a model set up, where the life of the villagers would see an upgrade at least, if not turn out to be ideal.

Much to Chando’s disappointment and that of others who moved to New Sehri Dars, however, the government had failed to provide separate land for livestock grazing in close proximity, as had been promised, they claimed. However, SECMC claims it to be the best resettlement project of the country.

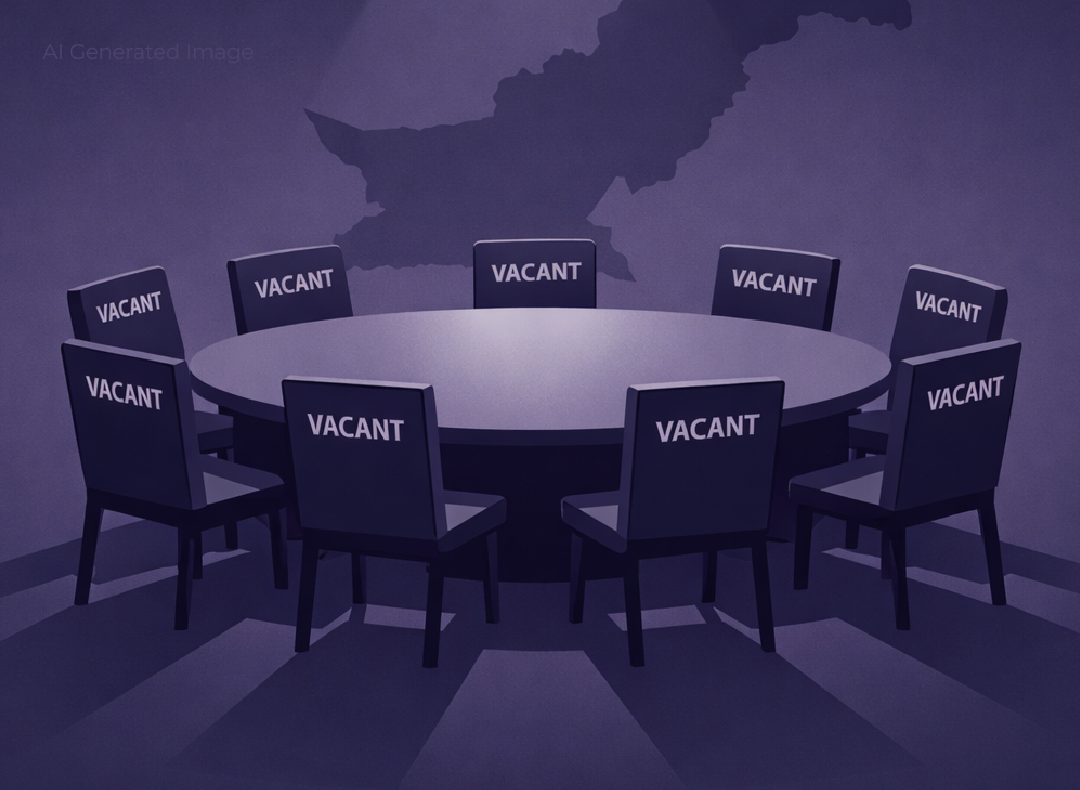

The model village was built for the families of villages displaced due to the coal-mining projects

The model village was built for the families of villages displaced due to the coal-mining projectsDesert economy

Tharparkar, the seventh largest and the only fertile desert in the world, is no longer a vast stretch of sand dunes and soil. Over the past few years, it has witnessed a spurting of the pockets of concrete jungle, now expanding rapidly to cover most of the desert rich in coal resources.

Since the inception of the Thar Coal Project — a venture aimed at mining coal from the area mainly for energy generation — many of the villagers, residing in the desert for years, had to move to newly built model colonies like New Sehri Dars. Some like Chando relented relatively easily; many others are apprehensive about the companies’ and the government’s promises which the latter have done little to allay.

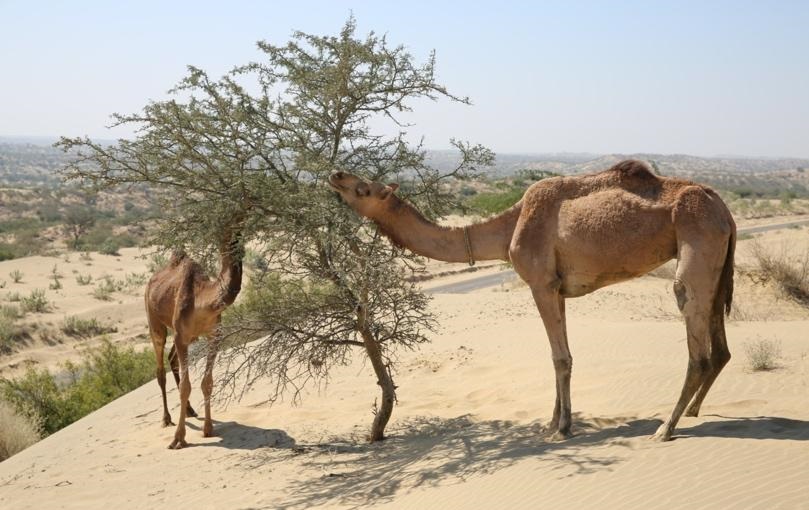

For one, the desert economy is primarily dependent on rain-fed agriculture, livestock and daily-wage jobs. According to the last census, conducted in 2006, its livestock population stood at over 41 million, making it 65 per cent of Sindh’s total cattle heads at the time. Hence, the region’s livestock serves as a major source of meat and milk in Sindh and its loss, besides leaving cattle owners in a fix, will spell trouble for the province as a whole.

According to residents, 95 per cent of the district’s population is dependent on livestock for survival. But model colonies such as the New Sehri Dars village have caused more harm to the livestock than working to their benefit, they claim, adding that in these new, supposedly modern settlements, they are bound to live a life they never wanted.

“We now have to buy food for the remaining animals we have,” lamented Chando, before going into a monologue about the hardships they have faced on a daily basis since moving into the new settlement. For Chando, their hardships are exacerbated by the rapid and irrevocable deterioration of environmental resources, which, among other factors, has also been attributed to coal mining and power generation projects initiated in the region.

Apart from livestock, these resources include a few acres of cultivable land, a source of livelihood for several local farmers who are now troubled by the environmental damage caused to their primary means of sustenance.

Model colonies have caused severe harm to the livestock in Tharparkar

Model colonies have caused severe harm to the livestock in TharparkarFor its part, the SECMC contends that they have provided locals with plenty of economic opportunities. According to the company, Thar Block-II has created approximately 50,000 direct and indirect livelihood opportunities for the locals who are earning a sustainable income.

On the entrepreneurial front, the Thar Foundation — the CSR wing of the SECMC — has capacitated and registered more than 100 local vendors, according to SECMC’s spokesperson. They further informed us “Over the past two years, Thar’s vendors have been given business in excess than 3 billion rupees. Moreover, more than 50 locals have been allowed to operate small businesses within the boundary of SECMC’s area of operation. That means that the locals have been allowed to set up tea stalls and or cafes within the operations zone of the SECMC, which largely cater to the labourers at the sites.”

More resettlement plans

Over the next few years, the government, as part of the coal mining efforts, plans to resettle, or as area locals have come to say, displace, scores of more families from their native villages to “model” ones. One such village is Warwai.

So far, however, the residents of Warwai have resisted the government's overtures to move them to the new settlements. “The area that they offered us for the model village was too far away from the main roads,” said Ghulam Mustafa, a teacher in Warwai. “And the groundwater was not suitable for us or our livestock,” he added.

Time and again, the residents of Warwai have questioned the rationale behind using coal for power generation when the practice has been abandoned in most parts of the world, largely due to its environmental implications.

“China is not mining coal in their own country but here they are investing a lot in these [coal power generation] projects,” pointed out Muhammad Rahim, 24, as resident of Warwai, whose wife died recently due to not being able to receive timely medication for high blood pressure. He blames her death on the lack of healthcare facilities in Tharparkar.

“I am not ready to lose another loved one to a lung disease, which is what the development in the area is going to cost us,” he said, adding that he had heard that some residents who had moved to the New Sehri Dars village had soon developed breathing problems.

“Just like emissions have polluted the air in Karachi’s industrial zones, the air over here, too, is being contaminated,” he complained.

Despite all his concerns, Rahim is not entirely against infrastructure development or even the coal mining projects. “But the government needs to resettle us in areas outside these development zones, given their hazardous impact,” he stressed.

On the other hand, the companies that are working in Tharparkar vehemently deny this line of reasoning. For its part, the SECMC claims that they not only follow all applicable national regulations and laws, but have also voluntarily adopted a number of international environmental regulations and standards.

Under the management’s strategy, monitoring reports drafted by third-party evaluators are regularly shared with Sindh Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) on a monthly basis and all parameters are found to be within permissible limits. What is ironic, however, is that the Sindh government, under which the SEPA falls, owns the majority stake in the SECMC at 51pc.

The SECMC further contends that it has undertaken various efforts, such as the Thar Million Tree Programme, to protect the environment. So far, more than 750,000 trees have been planted under the initiative, it claims.

Also

The construction of a barbed wire fence around Gwadar by the government: 'The locals will never accept it'

Ghulam Mustafa, a retired naik of the Pakistan Navy from Warwai, shared similar concerns. “Sehri Dars lies in between two chimneys [of the coal-fired power generation unit],” he said, “the results of which will start appearing in a few years.”

According to Mustafa, the residents of Warwai were ready to move but to a place of their own choice. “We have owned this land for over 300 years and have the right to keep it in our possession despite the faulty land ownership policies in the country,” he remarked. “It is difficult for us, the residents of Thar, to change our lifestyle and these model colonies are not an ideal habitat to lead the life we are used to,” he reflected.

Back in his home, Chando, while in agreement with Rahim’s take on the model villages not being suitable for the people of Thar, contests his views on the environmental impact of coal power generation. “These are mostly rumours and they believe them to be true,” he brushed off, adding that he had heard that the chimney located near New Sehri Dars was 700 feet high. “This will not have any significant impact on neither our health nor the environment,” he reckoned.

Amid these contradictions and uncertainties lives the Thar of today. Here, some are still resisting vacating their ancestral lands; others take less persuasion to give up their homes in the hope of a better life and for the betterment of the country.

The latter, like Chando, regret their decision already. But there is no turning back – neither for him, nor for the desert’s delicately-balanced ecosystem that is slowly being poisoned by the black gold that lies beneath it.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 4 Sep 2020, on its old website.

Published on 10 Jun 2022