The village of Thario Halepoto is surrounded by checkpoints and barbed wire. To its resident, Aziz Halepoto, it looks like an occupied territory.

There are high sand dunes on its two sides. A barbed wire fence on its south keeps its residents away from coal mines located next to it. On its fourth side is a checkpoint which leads to a coal-fired power plant.

Aziz has to cross this checkpoint twice a day -- first in the morning when he goes from his village to work at a restaurant next to the power plant and then in the evening when he returns home. Despite this being his routine, whenever he passes through the checkpoint, the Sindh Rangers personnel stationed there to check his identity card, enter his personal details in a register and body-search him. When the checkpoint gets a new set of personnel that does not know Aziz, he is also inquired as to who he is and where he is going.

Thario Halepoto is a part of Tharparkar district in the eastern part of Sindh province. The village is located 20 kilometers to the east of Islamkot town. Its population consists of 525 families (or approximately 3,270 persons) which belong to Halepoto, Meghwar, Bheel and Kolhi communities. Most of the villagers make their living by farming and raising livestock.

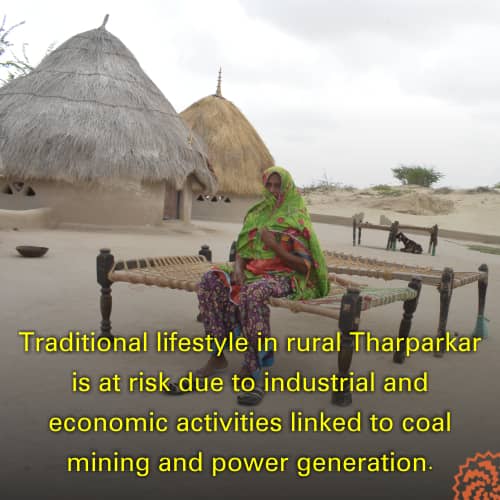

Aziz believes the industrial and commercial activities associated with coal mining and power generation pose a serious threat to the traditional way of life in his village. In order to keep local traditions alive, he always wears a traditional Sindhi cap and ajrak.

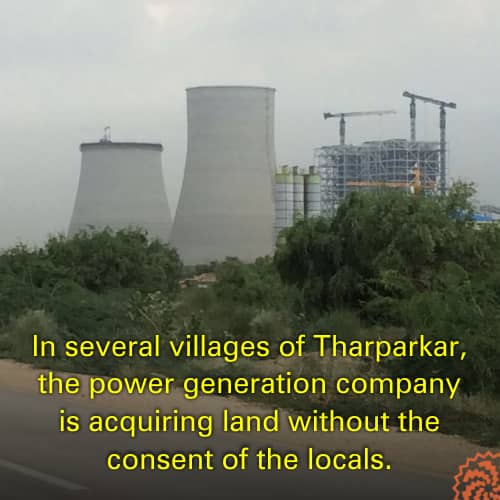

Coal-fired power projects were initiated in Tharparkar in 2013. In the first phase, coal reserves were divided into 13 different blocks, although only two of them, Thar Coal Field Block I and Thar Coal Field Block II, have become functional so far.

Thario Halepoto is located in Thar Coal Field Block II.

Aziz says the officials of Sindh revenue department first told the residents of his village in May 2013 that the government wanted to take their farmland and give it to the Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC) so that it could use this land for coal mining and electricity generation. The same warning was issued to several nearby villages as well.

But the people of Thario Halepoto were not ready to leave their land. On February 1st, 2014, when the then prime minister Nawaz Sharif visited Thar Coal Field Block I, about four hundred men, women and children of this village staged a protest and shut down all traffic on the road leading to a local SECMC office.

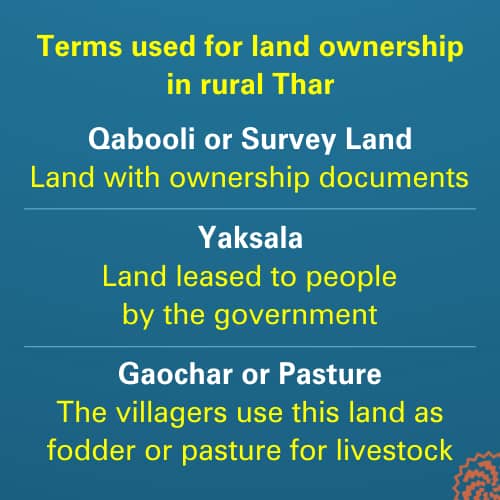

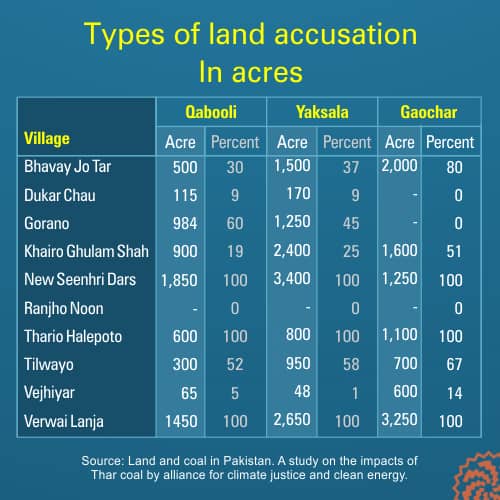

Their protest, however, proved futile and, with the help of district administration, the company seized 2,500 acres of land belonging to Thario Hallepoto. Of this, only about 500 acres of land was legally owned by 145 local families. In government documents, this is called “survey” land. Out of the remaining land, 700 acres were given by the government to 135 families on a yearly lease and 1,200 acres were used by the entire village as a collective pasture.

Despite the acquisition of all this land, Aziz says, SECMC has so far paid compensation to only 80 families that owned survey land at the rate of 180,000 rupees per acre. The government and the company, according to him, have not taken any steps to solve the financial problems of the rest of the villagers even though the acquisition of the land they were using has deprived all them of their sole source of livelihood.

SECMC, however, says it has been working on a plan since 2018 to relocate the residents of Thario Halepoto to a new place. Under this scheme, the company will build new houses for all of them besides providing them various basic facilities including a reverse osmosis water plant, schools, a hospital, a cemetery, a mosque, a temple, a playground, a market and roads.

The villagers are divided over it. About half of them are in favor of it while the rest do not approve of it.

Opponents of the project say the site chosen for their resettlement is located right in the middle of Block I and Block II, leading to fears that the new settlement will be fully exposed to environmental pollution caused by coal mining and power generation.

Aziz also says that moving to another location near the coal mines includes the risk that tomorrow another company will come around to generate more power and force them to leave their homes again. This explains why he and many other residents of Thario Halepoto say that, if they have to be resettled anyway, they should be moved closer to Islamkot town so that living near a larger town could give them an opportunity to improve their living conditions.

A festering wound

Senhri Dars village no longer exists as all its residential area and farmland -- comprising 1,200 acres of survey land, 3,500 acres of yearly leased government land and 1,300 acres of pasture land -- have been acquired by SECMC. All the residents of the village, which was once located within the boundaries of Block II, were relocated in December 2018 to a 'Model Village' built west of Thario Halepoto. This new settlement has been named as New Senhri Dars and it houses 320 families (around 2,000 people) belonging to Dars, Bheel and Kolhi communities. Each of their brick and mortar houses has three rooms, a kitchen, a courtyard, a chaura (traditional Thari hut) and a bathroom.

But people here are not happy because they are not the legal owners of these houses and they do not have any land on which to do farming. Although they have been given some land as a pasture but the people of Thario Halepoto have been using the same land for decades for rearing their livestock. Consequently, a dispute has arisen between the residents of the two villages over who can use it.

In the summer of 2020, says Aziz, Thario Halepoto’s inhabitants planted millet, barley and bean crops in this disputed land -- as they had always done -- but when the residents of New Senhri Dars found out about it, they send their cattle to graze on those crops. To prevent these animals from grazing, some young men from Thario Halepoto began to guard the land.

These young men were on their guard duty at 6 am on August 12th, 2020 when the police suddenly attacked them, Aziz alleges. The policemen came in about 10 vehicles and were accompanied by a bulldozer, he says. The youngsters blocked their way for an hour but, eventually, their crops were destroyed and seven of them were arrested and taken to an unknown location.

Mohsin Babbar, SECMC’s spokesman, calls the land dispute a “local” issue and absolves his company of any responsibility for it. At the same time, however, he calls the detained men as thugs and accuses them of hindering Thar’s development.

Many villages under the sky

Thar Coal Field Block I is located 13 kilometers east of Islamkot on the road to Nangarparkar. At the end of a rocky road along its southern wall is the village of Tilwayo.

A primary school is located on the left of the entrance to the village. It has a small room, a verandah and a few trees. Qurban Ali, 40, is sitting on a charpoy in the school’s courtyard. He is one of the few people in Tilwayo who have completed their matriculation.

He says that Sino Sindh Resources Company Limited, which works on coal mining and power generation in Block I, started the process of land acquisition in his area in April 2018 – without informing the local residents. In April 2019, they held a sit-in protest outside Islamkot press club to resist the acquisition of land. Their main demand was that they be consulted before any land is acquired in and around their village. They also offered to provide their land on a lease for a limited period of time but they received no response from the other side.

Also Read

Dry as dust: Rush to mine local coal worsens Tharparkar's long-standing water woes

Completely Ignoring their protest, Sino Sindh Resources Company Limited has so far seized about 800 acres of land in Qurban Ali’s village, of which 10 acres are under its use. Like in Talwaiu, the company is acquiring land in the nearby villages of Veerawah and Khario Ghulam Shah without the consent of the locals.

The total population of these three villages is 13,450. They have 3,800 acres of survey land owned by 390 families and 7,300 acres of land given by the government to 400 families on a yearly lease. They also have a 2,000-acre pasture which is shared by all 2,040 local families.

About 1,270 families residing in these three villages have never owned any land but another 200 local families have also become landless as a result of land acquisition by the company. These families were either cultivating government land on a yearly lease or they were growing crops on common lands.

Qurban Ali says only 240 families, which owned survey land in these villages, have been given compensation at the rate of 250,000 rupees per acre. He himself did not receive a single penny in return for his acquired land though, according to the documents in his possession, a Tharparkar Revenue Court in June 2020 declared him the formal owner of that land.

Such complaints regarding land acquisition, land pricing and compensation payment are so numerous and so severe in these villages that, on September 9th, 2020, Sindh government set up a committee headed by District Commissioner Tharparkar Muhammad Nawaz to hear and redress them. About 352 complaints have been lodged with it so far.

The local residents fear that many of these complaints will be rejected because most farmers do not have the documents that the committee is asking for. These range from marriage registration certificates to electricity bills and the proof of their names being on local voter lists.

Talking about these requirements, Nawaz says: “Unless the committee has basic documentary evidence, how can it determine who owns which land?” But he acknowledges that Tharparkar’s district administration does not so far have a clear policy on fixing land prices and resettling the residents of the villages affected by land acquisition.

In fact, Sindh government has been claiming for a long time that such a policy is being formulated. It, though, has not been finalized and implemented even though many years have passed since the first lands were acquired in Tharparkar for coal mining and power generation.

Published on 8 Nov 2021