Salman Sajjad Warraich irrigates 50 acres of his land with solar-powered tube-wells. A 62-year-old farmer from Ayyan Nagar Kalan village in Sheikhupura district, he was lucky to have installed these tube-wells in 2018 when the government was giving 80 per cent subsidy on their cost.

The subsidy, however, was conditional on water conservation: he was also required to install a drip irrigation system which provides fertilizer-mixed water directly to the roots of the crops. Although he received a 60 per cent subsidy on installing that system as well, the two projects together cost him as much as five million rupees.

Most farmers in Punjab do not have that kind of spare cash.

Naseeruddin Chishti, a 40-year-old resident of Punjab’s Pakpattan district, is one such farmer. He could only put together a part of the money required to install solar-powered tube-wells to irrigate all his landholding. Sometime ago, he installed tube-wells sufficient to provide water to 60 acres of his land. This cost him 3.5 million rupees, leaving him with no money to install more tube-wells to irrigate his remaining acres.

He then thought about taking a bank loan. His friends and fellow farmers, though, told him that the procedure of obtaining the loan was not only agonizingly slow but it also required many irrelevant documents which were painfully difficult to obtain. So, he finally gave up the idea of installing the additional tube-wells.

Aamir Gul, a 50-year-old landowner from Multan, is facing similar problems.

The brackish underground water at his farmland -- located in Yazman Mandi tehsil of southern Punjab’s Bahawalpur district -- leaves him with no option but to rely on canal water to irrigate his orchards of lemon, kinnow and orange spread over 12 acres. But, while the demand for canal water is increasing constantly in Bahawalpur (because of a continuous increase in the land being cultivated), the level of water in local canals is going down due to administrative problems and climatic changes.

He, therefore, wants to recycle the saline underground water through reverse osmosis (RO) technology and store it in a reservoir for use in times of canal-water shortage. This, though, requires the installation of a tube-well and an RO plant, both running on electricity. But the price of electricity supplied through grids by the government companies is so high that it will take the cost of running the project beyond his reach. This explains why he wants to pump and purify the underground water through solar-powered machinery.

The initial cost of this machinery, however, is too big for him to afford from his existing means.

In 2019, he approached various banks for a loan but the terms and conditions for the loans they offer for photovoltaic solar panel are too stringent for a middle-level landowner to meet.

According to Gul, the total amount of a bank loan given on solar panels required for running one tube-well and the interest rate on it reach 900,000 rupees which is double their market price. Additionally, the banks require the intending borrower to mortgage his land in order to secure the loan.

Another problem in this regard is that, instead of giving the lent money to the farmer directly, banks give it to the companies registered with them, he says. These companies, in turn, install solar panels of their own choosing. “You can do nothing if, at a later stage, these panels turn out to be faulty,” he says.

A recent report by the Rural Development Policy Institute (RDPI), a civil society organization based in Islamabad, states that banks are usually reluctant to give loans for solar panels because, in the case of a default, they do not want to bear the cost of taking over and selling the mortgaged land. The report’s author also says that no market mechanism exists for trade in second-hand solar panels. This hampers banks from re-selling the panels seized from defaulters, she says.

Even though the State Bank of Pakistan launched a scheme in 2016 under which banks were asked to provide loans for the promotion of solar energy, no solution has been found for the associated problems, she argues. For instance, she points out, banks do not lend money for buying batteries needed to store electricity generated by solar panels although these batteries cost as much as the panels do.

Similarly, she says, the government has provided no assurance to the banks that it will help them financially if they lose money as a result of loan defaults. This is despite the fact that such support is being extended to banks in some other loan schemes. The most notable example of this is the loans being extended under the New Pakistan Housing Scheme. The government bears 40 per cent of the loss incurred by banks due to the default of these loans. To arrange money for this contribution, the government has collaborated with the World Bank to set up a 15 billion rupees fund.

Zarak Khan, an assistant director at the State Bank of Pakistan, has endorsed the RDPI’s findings. At the launch of its report in October 2021, he said the banks have stringent conditions for solar energy loans because they have to bear all the loss accruing from loan defaults. He, however, expressed the hope that banks would ease their terms and conditions as and when the market for buying and selling second-hand solar panels starts developing.

License raj

Usman Bhatti, 35, a resident of Canal View Housing Society in Lahore, installed a 10 kilowatt solar power system on the rooftop of his house in January 2021. It cost him 1.1 million rupees.

His brothers now want to install a similar system but, according to him, the cost has risen to about 1.5 million rupees in the last 10 months. This increase is mainly due to the continuous depreciation of rupee against dollar. Consequently, the price of imported batteries and solar panels has gone up significantly.

Bhatti points to another problem too.

Since the electricity generated by his solar system exceeds his domestic needs, he wants to sell the surplus to the government-owned Lahore Electric Supply Company (Lesco). So, at the end of the last year, he applied to Lesco to obtain a license for the sale of electricity. As per the official procedure, Lesco sends all such applications to the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (Nepra); after Nepra approves the issuance of a license, Lesco officials install a special meter at the house where the solar system is set up so as to measure the amount of electricity it adds to Lesco’s grid.

According to the guidelines issued by the Alternative Energy Development Board, a government agency promoting renewable energy, the whole process to issue the license should take between 30 and 45 days. “It has been almost 10 months since I applied for the license but I have not yet received Nepra’s approval,” says Bhatti.

He claims to have had several meetings with Lesco officials and also paid bribes to get his application moving from one government official to the other. All to no avail, he says. He, therefore, has reaped no financial benefit from the solar system installed on his rooftop.

Imtiaz Hussain Baloch, Nepra’s Director General (Licensing) says most applications for licenses are approved within the stipulated time but he admits that some of them take longer than it should. The delay is either owed to the fact that the applicants do not submit the required documents in a timely manner or they fail to submit all the documents needed for the processing of their applications, he says. He also acknowledges that some government officials, too, deliberately delay the process in certain cases.

Also Read

Storing wastewater from coalmining: ‘Water gives life but it has become a threat to our survival.’

Referring to Nepra’s annual report for 2020-21, he says that 8,417 such applications have been approved so far. In Lahore alone, he says, 2,170 meters have been installed to link home-based solar systems with grids.

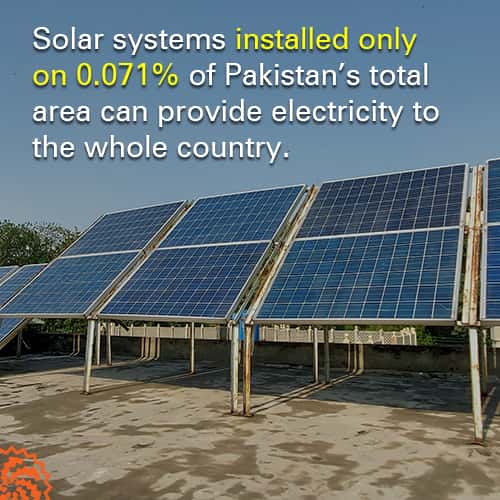

No matter how impressive these numbers may appear, all the solar systems connected to the grids are capable of generating only about 142 megawatts of electricity. This is not even one per cent of the total electricity required in Pakistan. The author of the RDPI report says the country, on the other hand, has the potential to generate many times more electricity from solar systems than it is doing now.

A 2020 report by the World Bank verifies this. It says the installation of solar power plants on just 0.071 per cent of Pakistan’s total area will be enough to meet all the current electricity demand of the whole country.

To make that possible, as the RDPI report puts it, the government needs to devise a comprehensive policy that removes all the administrative and financial barriers hampering the promotion of solar energy.

Published on 29 Nov 2021