Thirty years ago, in 1993, Shamim Bibi, 63, faced the responsibility of supporting her two daughters after her husband’s death. At that time, one daughter was five years old, and the other was one year old. Shamim Bibi, who is illiterate, possesses only farming skills, which she acquired while working with her father before marriage.

According to Shamim Bibi, who resides in Bhuta village in the northern district of Gujrat, accepting zakat and charity was not acceptable to her and her family, so her father provided her with an acre of land. Through farming on this land, she ensured that her daughters received education up to the intermediate level and arranged their marriages.

She says she would grow wheat on her land in winter, millet in summer, and a small amount of green fodder. She also kept a goat and later bought a cow. The household expenses were partially covered by selling the milk. A portion of the wheat and millet harvest was also sold to manage the costs of clothing, shoes, and education for her daughters.

“It was a good time; there were not so many expenses on crops, and food and drinks were not as expensive back then.”

She admits that farming is laborious, especially for a woman. However, it has not only saved her from being dependent on anyone but has also earned her the respect of people in the entire region.

“But now, farming has become very expensive. I don’t want to give it up, but the situation pushes me in that direction.”

She points out that there is no government scheme to provide cheap seeds, affordable fertilizers, or interest-free loans to small farmers like her.

Between the Jhelum River and the Chenab River, the district of Gujrat is a fertile agricultural region. According to the Department of Agriculture, the total cultivated area in this district is five lakh 72 thousand 911 acres. Out of which two lakh, one thousand 182 are non-irrigated. In the irrigated areas, wheat and rice crops are grown abundantly, while in the non-irrigated areas, besides wheat, millet crops are sown abundantly.

The last Agricultural Census conducted by the National Statistics Institute was in 2010. According to this report, 26 per cent of farmers in Gujrat own less than one acre of land, which is 10 per cent more than the rest of Punjab. Sixteen per cent of farmers in Punjab have less than one acre of agricultural land.

In Gujrat district, 35 per cent of farmers own less than two and a half acres, and 20 per cent own less than five acres of agricultural land. In the province, the rate of those with less than two and a half acres of land is 30 per cent, and those with less than five acres are 22 per cent.

The data indicates that the number of small farmers in the Gujrat district is significantly higher than in the rest of the province.

Chaudhry Amjad Ali, a 55-year-old resident of Pind Lahorian, situated 48 km southeast of Gujarat city, has two and a half acres of land where his family has been farming for several years. While he has been a farmer for the past two decades, he now says his courage is wavering.

“Cultivation costs are high and the income from crop production is low.” He is now contemplating leasing his land while engaging in manual labour.

According to him, cultivators who own just a couple of acres of land should either sell their land or rent it out, choosing manual labour instead, as their land will not be able to sustain their livelihood.

Haji Ghulam Rasool, a 60-year-old farmer from Ajnala town in Gujrat, owns two acres of agricultural land. Until four years ago, he used to lease and cultivate 15 acres, but now he only leases two.

He says that one reason for this shift is the rising expenses related to crops, and the second reason is that when the crop is ready, it doesn’t fetch adequate prices in the market.

Khalid Mahmood Khokhar, Chairman of Pakistan Kisan Ittehad, also says that farmers nationwide are facing challenges due to the significant surge in prices of agricultural inputs. However, the impact is particularly severe in districts like Gujrat, where cultivating many crops isn’t viable.

“The rise in crop costs has compelled small farmers to sell or lease their land or turn to livestock for sustenance.”

He says that labelling the country as an agricultural country or dubbing agriculture the backbone of the economy is a mockery of the farmers. Both farmers and consumers face difficulties, while the mafia benefits from hoarding.

He says that the government shows no interest in supporting farmers and there is a lack of emphasis on market control. A farmer with a two-acre plot cannot even secure a loan from an agricultural bank.

The loan details from the Agricultural Development Bank in Gujrat for 2023 reveal that all the loans granted to farmers were for an area of more than two acres.

Muhammad Aitzaz, the manager of the Agricultural Development Bank in Gujarat, stated that last year, loans totalling approximately four crore rupees were provided to farmers who own two to five acres of land at a seven per cent markup.

Farmers with more than five acres of agricultural land were granted loans of around Rs 22 crore loans. According to him, a farmer owning an area of two to five acres can obtain a loan of up to Rs 25 lakh, while farmers with more land can secure up to Rs 50 lakh.

Muhammad Aitzaz says that the government is extending financial support to farmers to acquire agricultural machinery in addition to agricultural loans.

Haji Ghulam Rasool disagrees with this. He says that all claims of the government providing subsidies to farmers for loans or agricultural machinery are false and fabricated.

He says that small farmers do not get loans. Even if they approach the bank, numerous conditions are imposed, making it impossible for them to fulfil the requirements.

Khalid Mahmood Khokhar, President of Pakistan Kisan Ittehad, also expresses scepticism regarding the accuracy of figures for providing bank loans, subsidies, or interest-free loans for agricultural machinery to assist farmers.

“Banks offer low-interest loans to those looking to establish businesses or factories worth billions of rupees, but small-scale farmers struggle to secure loans, and even if they manage to, the interest rates are high.”

Zaheer Abbas Gul, a field officer in the Department of Agriculture, points out that in addition to the high cost of inputs and fluctuating crop prices, another significant challenge for small-scale farmers in Gujrat is the fragmentation of their land.

He says that while the paperwork may indicate that farmers own two and a half acres, the reality is that their land is often fragmented into smaller plots scattered in different locations. Gul further says that the consolidation of agricultural land in villages is paramount.

Also Read

Empowering impoverished farmers: navigating modern agriculture challenges

“If the land is divided into smaller pieces, cultivating becomes challenging. Contract farmers also prefer larger, consolidated areas for farming,” Gul says.

According to him, farmers are also contributing to the declining income in agriculture.

“Most farmers are not interested in modern research on seeds and fertilizers. They often follow the advice of vendors who sell them substandard seeds and fertilizers for higher profits.”

Zaheer also admits that the agriculture department is understaffed, with each field officer overseeing around 100 villages, making it challenging for them to cover all areas adequately.

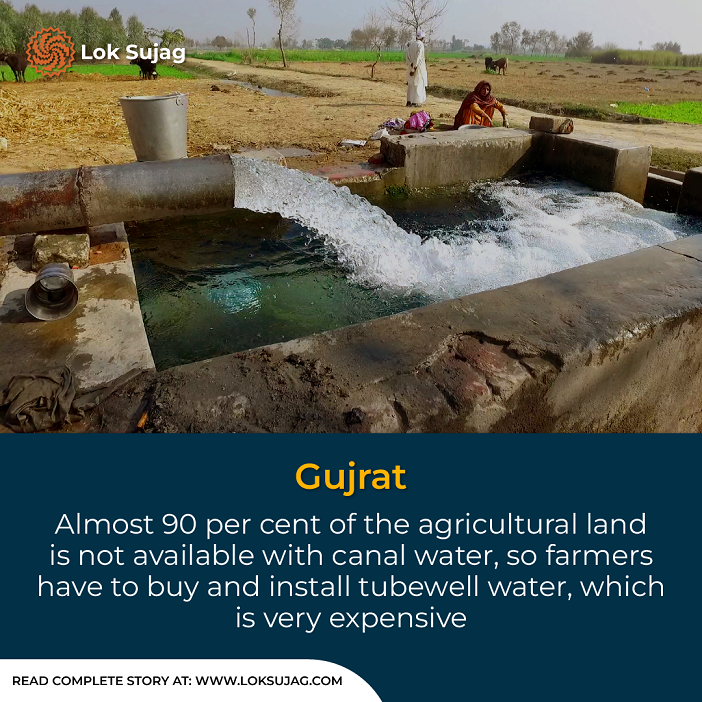

According to him, access to water is a problem for small landowners. “Almost 90 per cent of the agricultural land in Gujrat is not equipped with canal water, which is why tube well water needs to be bought and used, which proves to be very expensive for us.”

He says that small farmers are unable to benefit from government incentives for water or agricultural machinery because they can only afford to purchase a tractor if they have Rs 25 lakh. Similarly, installing solar panels or other irrigation equipment remains beyond their financial reach.

He recommends that if the government offers a loan of up to Rs one lakh for each crop to a farmer with one or two acres of land, it would boost the farmer’s income and enhance production.

Haji Ghulam Rasool, who has contested local government elections multiple times, believes that the solution to alleviate the problems of small-scale farmers lies in the local government system. He says that MPAs or MNAs do not adequately address farmers’ concerns in the assemblies.

Khalid Mehmood Khokhar, Chairman of Kisan Ittehad, says it is imperative to provide fertilizer, seeds, and other agricultural inputs at affordable rates at the Union Council level to sustain small-scale farmers.

“Guiding farmers on suitable crops each year can lead to better returns. Implementing crop insurance can help cover potential losses for farmers,” he concludes.

Published on 2 Jan 2024