Radha does not have shoes. Every day she has to walk barefoot in scorching heat from her home to work in the fields.

Radha, 15, lives with her mother, Pappi Bibi, and two younger siblings in a village called Dargah Rahu Mushaq in district Tando Allahyar’s tehsil Jhandu Marri. Her house is located inside a huge cattle shed two kilometers east of the highway that links Hyderabad with Mirpur Khas. Surrounded by swaying cotton fields and banana orchards, the shed looks beautiful at first glance but within it about 20 people, including Pappi Bibi and her siblings, live within it in three rudimentary rooms. They share their living space with their utensils and beds, eating, drinking and sleeping in the same cramped rooms.

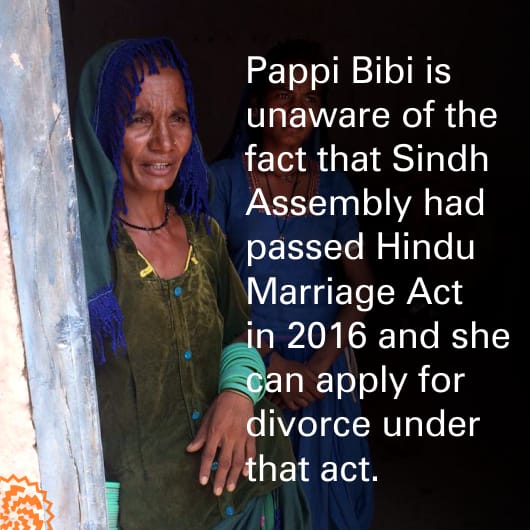

Pappi Bibi is only 31 years old in the government record but she looks much older than her age. The wrinkles on her face and the fading lines of her hands show that life has not been kind to her. Sitting on a charpoy in the shade of an acacia tree, she narrates the story of her separation from her husband. Sadness, anger and helplessness are visible simultaneously on her face.

Pappi Bibi was married about 20 years ago to a man named Mohan who belongs to her own scheduled caste Hindu community. She was very young at the time yet her husband, often intoxicated with alcohol and hashish, used to beat her with a club. Pointing to a big scar on her temple, she says that once her skull was ruptured due to the beating so she had to get five stitches to mend the wound. She also says that her husband had relations with some other women whom he used to bring home as well.

When Pappi Bibi did not have any strength left to endure Mohan’s violence and infidelity, the elders of her community separated her from him. Under the terms of separation, Mohan was obliged to take care of Pappi Bibi and was also told to give her three thousand rupees every month to raise their children. But she says he has not given her a single rupee so far even though he has been spending time with her even after the separation. Radha's ten-year-old sister and five-year-old brother have been both born as a result of his occasional visits.

The irony is that Mohan is living a prosperous life in the Sultanabad area of Tando AllahYar district, says Pappi Bibi. "He has 2.5 acres of his own land and also works on the lands of a local landlord but, despite having all these resources, he does not even take note of his children," she says.

As a result, Pappi Bibi has been raising her children over the last many years on her own by working in the fields but her income is so meagre that she cannot even afford to feed and clothe them properly.

Radha's marriage is also her biggest worry. Because girls in her community are married off at a very young age, her relatives taunt her that her daughter is still unmarried. She becomes emotional as she talks about it and says: "How can I marry my daughter when it is difficult for me to give her a square meal?"

She wants to force her husband with the help of police or courts to pay for the maintenance of the children but does not know how to do that. She is also unaware that the Sindh Assembly has passed a law in 2016, the Hindu Marriage Act, which gives her the legal right to do so.

The biggest hurdle in the way of Pappi Bibi to approach the police or the court, however, is that she does not have any documentary evidence that she has been married to Mohan. She does not have a marriage certificate or the birth certificates of her children on the basis of which she can claim to be his wife. The only identity document she has is an expired national identity card, but it also carries her father's name instead of her husband's.

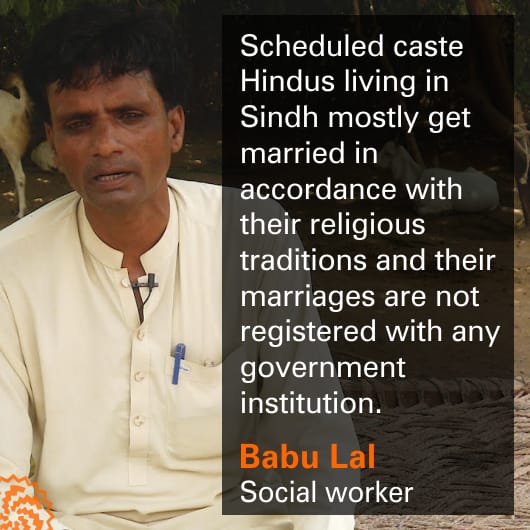

Babu Lal, a social worker based in Jhandu Murri, says one of the main reasons why women like Pappi Bibi do not have such documents is that scheduled caste Hindus living in Sindh mostly get married in accordance with their religious traditions and their marriages are not registered with any government institution. "Scheduled caste Hindu communities are not aware that there are laws in the country under which they can register their marriages and births of their children with local union councils," he says.

People belonging to these communities realize the importance of these documents only when they have no other choice but to go to the government officials and courts to get their rights, he says. “When they realize that they do not have the right to take this legal path in the absence of identity documents, they can do nothing but curse their ignorance, poverty and fate," he adds.

When divorce alone is not a solution

Nomi Bibi is about 37 years old. She lives with her parents in Isa Khan Mori area of Mirpur Khas district. These days she is residing with her sister in Mubarak Colony in Mirpur Khas city where she and her four children are lodged in a small room.

There is no electricity in their lodging. Her 16-year-old son, Mukesh, therefore, has installed a fan which runs on two small electric batteries. It can barely fan two people. Apart from Mukesh, Nomi has two more sons and a daughter who is older than all her siblings.

Looking weak and thin, Nomi speaks in a very low and frightened voice. She says she was 17 years old when her parents married her off in 2001 to a man named Maoji from their own Kolhi community. After a few months of marriage, her life became very difficult because her husband did not do any work and remained intoxicated with alcohol and hashish all day long. When Nomi started selling bedspreads that she would make at home so that she can run her household, her husband started asking her for money.

"In the beginning, when my husband asked me for money for alcohol, I would give him some of the money I had saved," she says. His demands, however, kept increasing and when she did not give him money, he would threaten to burn all the bedspreads that she had made.

In the end, he did just that. One day, in a state of extreme intoxication, he not only pulled out all the bedspreads from their boxes and set them on fire but he also stabbed Nomi with the backend of a knife, causing a deep wound in her head.

“Maoji not only tortured me but he also often brought some women home with him in a state of intoxication and asked me to serve alcohol to all of them”, she says. Wiping away her tears, she says that her husband used to do all these things in front of her children. “Often in a state of intoxication, he even stripped me naked in front of the children, making me lose all my self-respect.”

She endured all this for many years but then some political activists in her area screened a documentary. It was about the Hindu Marriage Act 2016. The documentary stated that the law allowed Hindu women to get divorce from their husbands.

"As soon as I heard this, I stood up and announced in front of everyone that I would use this law to get a divorce from my husband," says Nomi.

She finally filed for divorce in 2019 at a family court in Mirpur Khas under the Hindu Marriage Act. Sat Ram Das, a Hindu lawyer, appeared in the court on her behalf while her plea was heard by a female judge who, after hearing arguments from both sides, ruled that Nomi could have a separation from her husband. She also wrote in her judgment that Maoji would not only return her entire dowry but also pay her 5,000 rupees per month for the upbringing of each of their four children.

It has been more than two years since that decision was made but Nomi says, "To this day, my husband has neither paid a single rupee to support the children nor has he returned the dowry." Instead, he abducted her youngest son, Sunil, from a playground in Mubarak Colony a couple of weeks ago. Nomi says she has "no idea where the child is".

At the same time, however, she is painfully aware of the fact that Maoji has no money to give her. She says, "My husband is unemployed and he begs for money. How will he pay 20,000 rupees a month to support his children?"

She is, therefore, content with the fact that she has gotten rid of him. She no longer wants to have any contact with him and says, "I work in people's homes to support my children so that I do not have to ask him for money."

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 9th July 2021, on its old website.

Published on 17 Feb 2022