On a humid August morning in 2020, Muhammad Rasheed was woken from his sleep by a group of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) activists. They briefed him about the government’s Sehat Sahulat Program and the financial perks associated with it – and left.

A resident of a village in Dipalpur tehsil of Okara district, he was pleasantly surprised by their visit. A heart patient, he was spending more money on his treatment than his family’s cumulative income. So, he immediately had himself registered as a beneficiary of the program.

Soon afterwards, he suffered pain in his chest and was rushed to an Okara hospital associated with the program. A thorough examination later, the doctors told him that he needed a heart surgery.

Subsequent to this advice, Rasheed remained admitted in the hospital for over two weeks but his surgery did not take place. What made his wait worse was the cost of staying in the hospital and medicine bills. Though he was informed that his medical expenses will be paid by Sehat Sahulat Program, in reality he paid for all his medication from his own pocket – incurring an expense of 9,600 rupees in two months. He also paid an additional 2,400 rupees for his tests (though, he alleges, the hospital gave him an invoice for only 800 rupees).

In the end, Rasheed was told that he did not need a surgery – except that his Sehat Card was charged for it.

How the program works

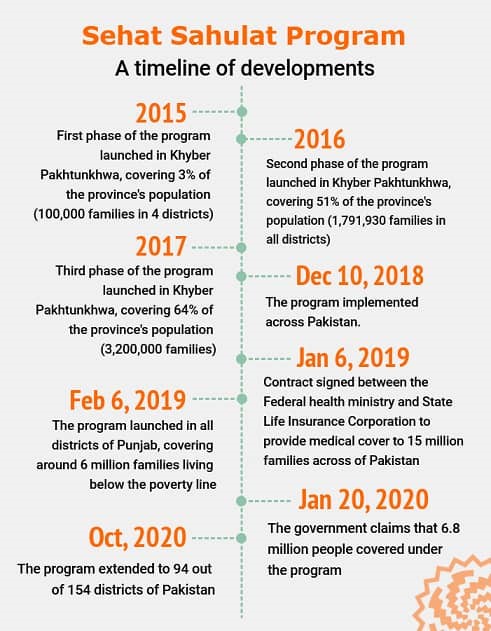

Sehat Sahulat Program was initially launched in 2015 in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province where PTI has been in power since 2013. Its primary objective has been to provide free medical treatment to people living below the poverty line – or those earning less than two dollars a day.

After winning the 2018 general elections and forming the federal government, PTI expanded the program to entire Pakistan and announced that it will have 25 million beneficiary families across the country by January 2019.

The program allows a beneficiary family to get medical treatment worth 720,000 rupees every year. The beneficiary is also entitled to receive 3000 rupees every year as the cost of travel between home and hospital. In case a member of a beneficiary family dies, their heirs will get 10,000 rupees for their burial.

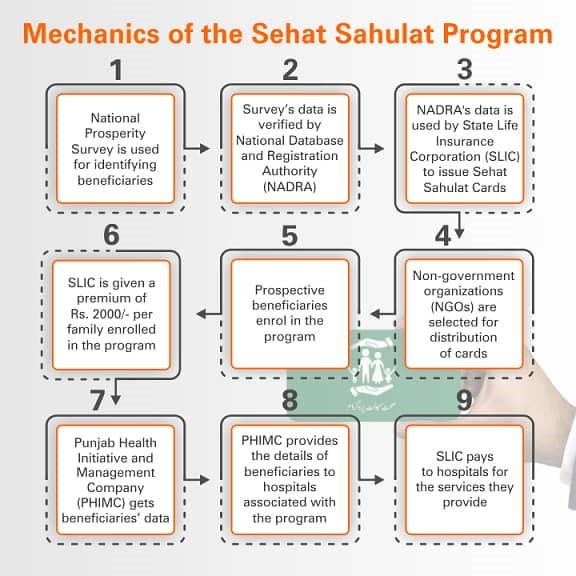

To finance the program, the government devised a medical insurance system under which it pays a premium of 2000 rupees to an insurance company on the behalf of every beneficiary family. To get the best services in return for this premium, the government invited various insurance firms to bid for offering medical coverage to the beneficiaries. The government’s own company, State Life Insurance Corporation (SLIC), ended up winning the bid.

In Punjab, it is overseen and implemented by the Punjab Health Initiative Management Company -- a government owned corporate entity with headquarters in Lahore. Without wanting to be identified by name, one of its directors says his organization coordinates between the government, hospitals, SLIC and the beneficiaries.

He, however, refuses to give a clear answer to queries about the money the government is spending on the program. He calls it a “hefty amount” and puts it roughly at 50 billion rupees “at the very minimum”.

SLIC also refuses to reveal how much money it is receiving from the government as premium and how much it is giving out to the beneficiaries of the program. “This is not public information. Instead, it is a confidential matter among the stakeholders,” says a SLIC representative who does not want to be identified by name. He does say that the government owes SLIC seven billion rupees in outstanding premiums.

The program has 458 private hospitals affiliated to it across Pakistan. A majority of these, 267 to be exact, are located in Punjab’s 36 districts. In 29 of these districts, the program covers only those living below the poverty line but in the remaining seven – located in Sahiwal and Dera Ghazi Khan divisions – it offers a medical coverage to everyone.

Or at least it claims to do so.

The situation on the ground belies this claim. While the population of Sahiwal division – comprising the districts of Sahiwal, Okara and Pakpattan -- exceeds seven million, it has only six private hospitals associated with the program. The total number of beds at these hospitals is a paltry 179. The number of Sehat Sahulat Program beneficiaries in the division also stands way below its total population.

(Sub)standard operating procedures

On 4th June 2021, Dr Syed Karim Shah Shirazi is sitting in an air-conditioned office inside Ali Shirazi Poly Clinic, a Sahiwal-based private healthcare facility that he owns. Outside the room, patients and their attendants can be seen roaming around in sweltering heat. Carrying their Sehat Sahulat Program registration cards, they are beseeching the clinic’s management to provide them treatment but Shirazi is adamant: his clinic will have nothing to do with the program and its beneficiaries.

A retired associate professor of surgery, he narrates how the representatives of SLIC gave him a presentation on the 500 medical procedures that the program covers -- as well as their prices. He refused to join it because he thought the prices were not good enough to provide a quality treatment.

Yet, he complains, his clinic continues to appear in the government lists as being associated with the program – hence the crowd of patients outside his office.

Even otherwise, Shirazi is highly critical of Sehat Sahulat Program. According to him, “it has too many flaws to be useful for patients”. For one, he says, it offers medical services at such low prices that no self-respecting doctor or healthcare facility can afford to provide those services at those prices. “Because of low prices, hospitals and doctors are providing substandard facilities and low quality treatment to the program’s beneficiaries,” he says and claims his hospital has handled many patients who were treated poorly by healthcare facilities associated with the program.

Shirazi also believes that it is inducing “several violations of the standards” set by a provincial regulatory body, Punjab Healthcare Commission. For instance, he says, it is allowing simple medical graduates to perform complicated procedures which they are not trained for. “It is, thus, promoting quackery.”

Dr Abdul Rehman Sani does not agree with this assessment.

Reclining on a leather chair in an office at the Jinnah Medical Complex, a private hospital in Sahiwal, he proudly talks about his long career of working in various hospitals across Punjab as an orthopedic surgeon. He says he has performed 180 major orthopedic surgeries on patients covered by Sehat Sahulat Program after joining Jinnah Medical Complex in October 2020.

Sani claims the program’s pricing mechanism is offering “different price packages to different hospitals/clinics”, depending on the quality of their treatment and services they offer. Some, according to him, are “given a handsome compensation while others are not given much”.

A director of the Punjab Health Initiative Management Company confirms this, albeit obliquely. “We offer monetary compensation to hospitals based on the medical facilities they have as well as the experience and qualification of their doctors,” he says. There, however, is no ways for the beneficiaries of the program to know which hospital has been categorized to have better facilities and better doctors.

The director also claims that his company reviews the complaints filed by the beneficiaries every evening. “These are followed up in order to prevent a potential backslide in the program,” he says. “The performance of hospitals is also monitored every couple of months and they are given instructions to improve their existing flaws.”

Flawed from the start

Punjab Health Initiative Management Company claims 8.59 million families have become the program’s beneficiaries in Punjab alone. The data available on the website of Sehat Sahulat Program, on the other hand, says the total number of registered families across the whole of Pakistan is 7.83 million.

The director claims the discrepancy has been caused by the fact that the website of Sehat Sahulat Program is not updated. Yet the numbers he is giving seem to be rather bloated. If one goes by them, more than half of all the 17.1 million families living in Punjab should have become the program’s beneficiaries by now. The evidence on the ground certainly does not support that.

Then there are some other snags in official statistics.

To cite just one, the beneficiaries of the program are chosen in accordance with the National Prosperity Survey which identified that 27 million Pakistani households are living below the poverty line. As per the government’s plans, Sehat Sahulat Program aims at providing free medical care to 15 million of these households. This means that it will not cover at least 12 million poor families.

The other problem with these numbers is that they are a decade old since the last National Prosperity Survey was completed in 2010. It is, therefore, reasonable to assume that the number of poor families living in Pakistan might have increased since then because of the increase in the country’s overall population. This suggests that the number of poor families left out of the ambit of Sehat Sahulat Program could be higher than 12 million.

Additionally, as Javed Ahmed’s struggle shows, the selection of the beneficiary families seems to be quite arbitrary.

A 64- year-old man in a frail condition, Ahmad maintains his balance with difficulty as he paces across the Punjab Institute of Cardiology (PIC), a public sector hospital in Lahore. On a hot day in May 2021, he is there for his angiography.

Only a year ago, he ran a small vehicle repair shop on Lahore’s Jail Road but then he had to shut it down because he became too ill to work.

Also Read

Breathing uneasily: Oxygen shortage in government hospitals endangers the lives of Corona patients

Ahmad is a chronic heart patient. He underwent a coronary bypass surgery seven years ago but, despite regular checkups, his health deteriorated again last year. By February 2021, his chest started contracting again with pain.

With his income from his shop gone, the financial burden of his healthcare fell entirely on his two sons. One of them works as a domestic help and the other has a clothing store in Baghbanpura, a mostly working class area in northern Lahore, where Ahmad also lives with his wife and sons. “My family’s aggregate income is 25,000 rupees per month which barely helps us make ends meet,” he says.

A few months ago, Ahmad chanced upon a group of his neighbors in Baghbanpura gathered outside a small kiosk. Ahmed too joined the crowd. A poster there had ‘Sehat Insaf Card’ written on it in bold letters along with instructions on how to register for Sehat Sahulat Program. Two activists of the ruling PTI sat inside the kiosk, jotting down details from Computerized National Identity Cards (CNICs) of local residents. The activists were promising everyone that they will receive the proof of their registration in 15-20 days – provided they were found to be eligible for it.

Ahmed too provided his identity details to them and started waiting for his registration to get through.

A week later, the kiosk disappeared. Ahmed subsequently made several telephonic attempts to contact the registration authorities but he did not receive any answer. When eventually he got a response, he was informed that he was ineligible to be a beneficiary of the program.

As his financial reserves approached their end, Ahmed started losing hope and gave up his treatment entirely. It was only after strong remonstrations from his family that he resumed going to the Punjab Institute of Cardiology for his checkups.

During one of these checkups, a nurse advised him to register for Sehat Sahault Program again. He told her that he was not eligible for it. When she insisted, Ahmad applied again.

And again he was told to wait for 15 days – making him put his treatment on hold in the anticipation that he may finally get some financial help from the government.

Kulsoom Bibi, 46, had to undergo a similar ordeal.

Her husband, 53-year-old Iftikhar who runs a tea stall near Lahore’s Anarkali bazaar, fell ill recently. He was admitted to Data Darbar Hospital, a government-run healthcare facility near the old city of Lahore. Doctors there said he has developed a cyst inside his body and needs an urgent surgery to take it out.

Bibi did not know how to finance her husband’s treatment -- until one day she spotted a Sehat Sahulat Program poster glued to a tree just outside the hospital. She hurriedly noted the phone number written on it and placed a call on it immediately. She received no response.

Many unanswered calls later, she decided to visit the office of Sehat Sahulat Program located in another part of Lahore. “I had saved some money to spend on my husband’s medical tests but I ended up using that on travel to the program’s office,” she says.

When, after multiple visits, she could not get registered, she dialed the phone number given on the poster and called again. To her utter disappointment, she was told that her family was not eligible to become a beneficiary of the program.

Since she had no savings left to have her husband treated, she approached her neighbors and relatives for help. “They helped me put together the money required for his surgery,” she says.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 25 Jun 2021, on its old website.

Published on 10 Jun 2022