A recent school day in Sindh province’s Shahdad Kot town started with a morning assembly – just like it does everywhere else in Pakistan. Children dressed in school uniforms lined up in a playground. One of them recited verses from the Quran and another intoned a naat in the praise of the Prophet of Islam. A passionate patriotic speech by a grade three student followed.

“Had it not been for Pakistan Resolution, those Hindus would have eaten us alive,” he said. The crowd in front of him erupted in a teacher-led clap. Several students, though, moved uneasily in their queues. They were Hindus.

The narrator of this incident is a 24-year-old Hindu social activist from Shahdad Kot who does not want to reveal her identity. “No one in the school management bothered about the fact that there were many Hindu students – as well as some Christians – among the assembled children,” she says.

During her own school years, she, too, had faced hostile attitudes on multiple occasions only because of her religion. “Other students did not want to have anything to do with a Hindu girl,” she says. “They would not even eat in front of me because they thought that their food would become impure if I so much as touched their lunch boxes by accident.”

This intolerance originates mostly, if not entirely, from what Pakistani students read at school. The government-approved textbooks are replete with material that is not only discriminatory towards non-Muslim Pakistanis but, in worst cases, also incites hatred towards them. Phrases like the “cunning Hindus plotted against the Muslim League…” are found quite commonly in many textbooks.

The Single National Curriculum only makes it worse.

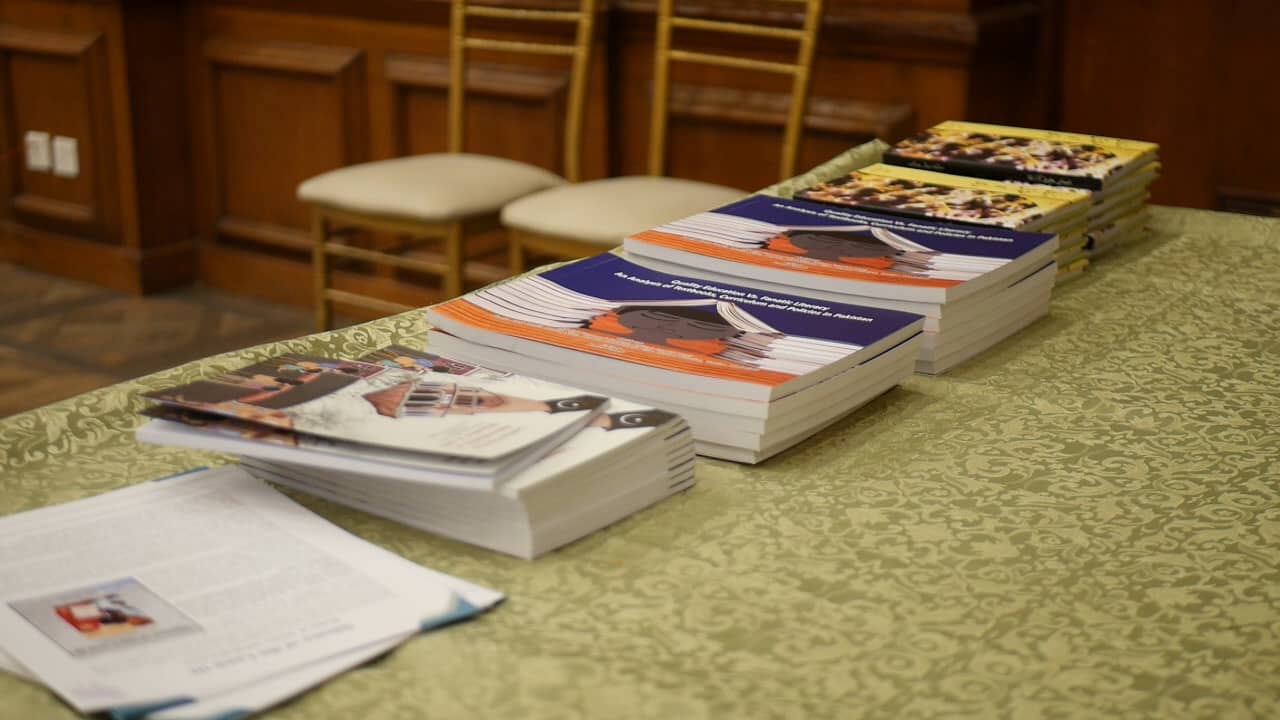

Now that model textbooks have been published under this federal government initiative, human rights activists and educationists are criticizing it for not taking into consideration the concerns of non-Muslim Pakistanis. A study carried out by a Lahore-based think tank, Centre for Social Justice, which focuses on the rights of religious minorities in Pakistan, has pointed out that a lot of content in model textbooks is discriminatory in religious terms, includes hate speech and is biased towards non-Muslims.

The study, titled as Quality Education vs Fanatic Literacy – an analysis of textbooks, curriculum and policies in Pakistan, shows that four out of seven chapters in the model textbook for grade two Urdu contain information about Islam. Even though these concern subjects such as essay writing and sentence construction, examples in them have been taken only from Muslim religious history, the study says. The book, indeed, repeatedly mentions how being a Pakistani is synonymous with being a Muslim.

That the Single National Curriculum will result in the educational isolation of non-Muslim Pakistanis is a conclusion many human rights activists and researchers on education have arrived at. Lahore-based teacher and anti-nuclear peacenik A.H. Nayyar is among the most prominent of them.

He says “a large amount of religious content, including religious instructions, has been included in textbooks for compulsory subjects such as English, Urdu and Pak Studies. The students belonging to religious minorities, according to him, “have no choice but to learn all this”.

Ayesha Razzaque, a researcher who often writes newspaper columns on educational subjects, echoes these views. “These textbooks are going to be alien for non-Muslim children because most of the names used in them are Muslim names and there is barely any mention of non-Muslim writers or prominent figures in them,” she says. She also wonders if asking religion-centered questions -- such as how to become a good Muslim -- in an Urdu textbook is pertinent to the teaching of that language.

Dr Faisal Bari, a dean at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), has a similar opinion. He believes model textbooks – as well as the ones being already used in schools – are “blatantly biased” against religious minorities. “These books do not show any non-Muslim role models,” he says.

Feminist groups have also raised concerns over religious material included in the new curriculum. Pakistan’s oldest women’s rights collective, Women Action Forum, has issued a statement in which prominent educationists such as Neelum Hussain and Rubina Saigol have called the government efforts to devise the Single National Curriculum as discriminatory and non-inclusive. They see the initiative as an attempt to further Islamize education than it already is.

Seeking unity, promoting disunity

The foundation stone for the Single National Curriculum was laid by the federal government of Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN) during its 2013-18 tenure. That government set up a National Curriculum Council in 2014 with the objective to develop a “minimum” curriculum that “ensures Minimum National Standards in all subjects and emphasizes on national ideology and societal needs.” The council had 46 members, including the federal education minister, four provincial education ministers, two regional education ministers, chairman of the Higher Education Commission, chairmen of provincial textbook boards, representatives of the educational institutions being run by the army, navy and air force, eminent scholars and educationists and heads of various associations of Islamic seminaries.

As a first step in the task assigned to it, the council came up with a National Curriculum Framework which highlighted five challenges that the Single National Curriculum must address. These included i) safeguarding and promoting the ideology of Pakistan; ii) ensuring integrity, solidarity and national cohesion; iii) developing and maintaining uniform standards in learning and assessment; iv) ensuring uniformity in diversity; v) honoring national and international commitments on fundamental rights. The authors of the framework also emphasized that one of their four main concerns was the promotion of “harmony, national cohesion and religious acceptance while keeping Islamic integrity intact”. A subcommittee of the National Curriculum Council later added another concern to this list: “integrity of Muslim Ummah”.

These excerpts gleaned from a government document containing the National Curriculum Framework make one thing quite explicit: an exercise that essentially started as a means to set minimum national standards to improve the quality of education across the country soon became a tool for perpetuating Pakistan’s Islamic identity.

When the ruling Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) took over power in August 2018, it adopted this National Curriculum Framework even when it was prepared by the government of its staunchest political adversary. Subsequently, in 2019, the Federal Ministry of Education and Professional Training set up a national curriculum committee which started the process of formulating the Single National Curriculum.

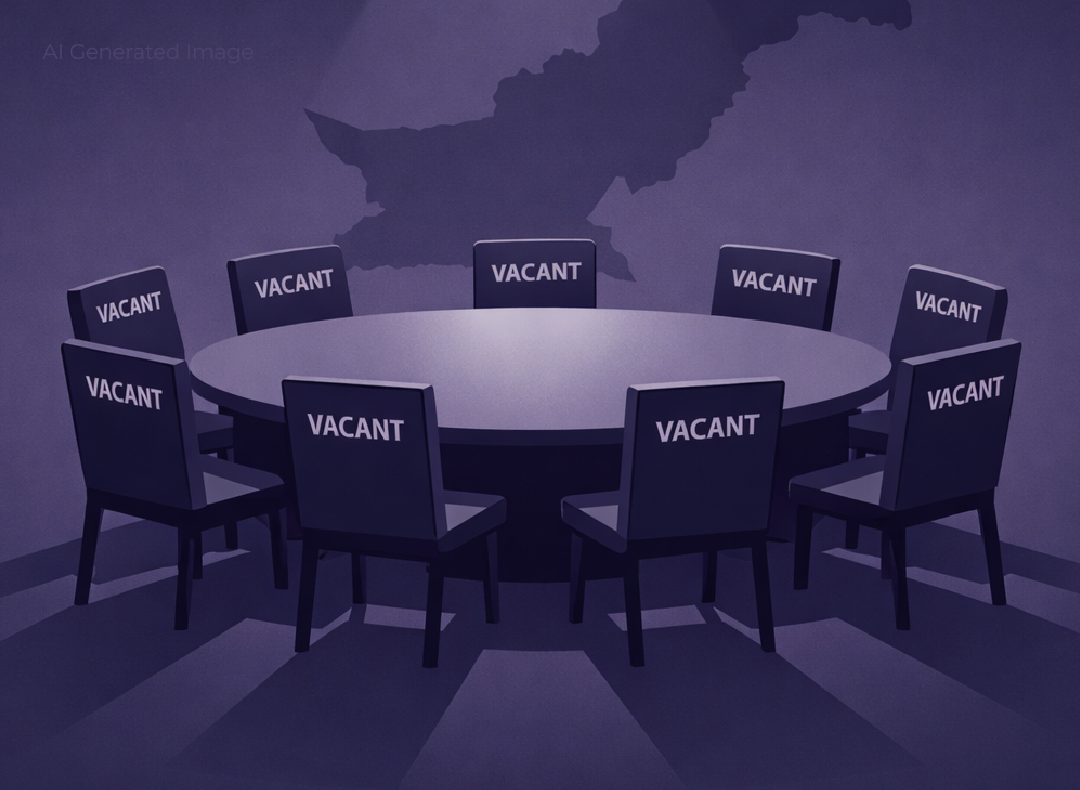

As soon as the first draft of this curriculum was released in the summer of 2020, criticism came in flooding. Initially, educationists from across Pakistan questioned the transparency of the process through which it was drafted. The government then issued a list of 400 experts belonging to different parts of the country who, it said, were consulted on the new curriculum.

'This will perpetuate ‘otherization’ that students from minority communities already face in schools'

'This will perpetuate ‘otherization’ that students from minority communities already face in schools'Mariam Chughtai, a Lahore-based educationist who has worked closely with the government on the new curriculum, dismisses the allegation that the curriculum was drafted behind closed doors. “We convened an education conference that lasted four days and in which 400 experts were heard and taken into confidence,” she says.

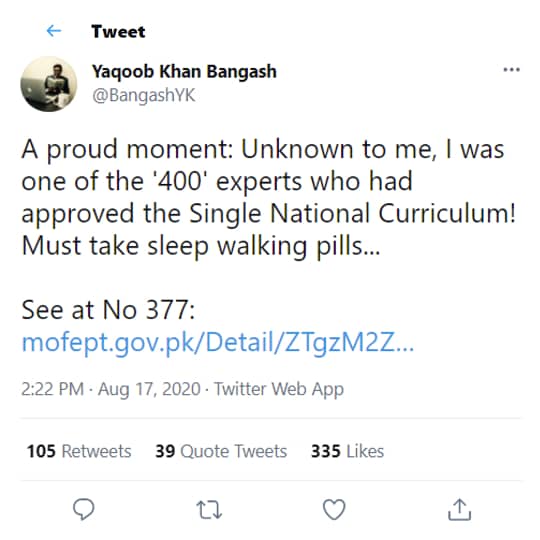

This claim has been denied in at least a couple of well-publicized cases. Dr Yaqoob Bangash, a Lahore-based historian, said in a tweet last year: “A proud moment: Unknown to me, I was one of the '400' experts who had approved the Single National Curriculum! Must take sleep walking pills...”

Talking to Sujag, he says, “I have no idea why my name was in the list of the experts”.

Amir Riaz, a publisher and human rights activist working in Lahore, was also surprised to see his name in the list of experts. According to the government, he was designated as a focal person for Punjab. He denies having been contacted by anyone for the drafting of the Single National Curriculum even when he acknowledges that he has worked over the last ten years with various governments on developing and publishing textbooks.

Some provincial and regional governments, too, have raised questions about inclusivity in this process. The governments of Sindh, Balochistan and Gilgit-Baltistan have all stated that they were not duly consulted. This is how Peter Jacob, a Lahore-based human rights activist who heads the Centre for Social Justice and also chairs a working group of activists and researchers on inclusive education, comments on the situation: “Three regions have expressed their concerns and two of them have explicitly said they would not follow the new curriculum.”

He also points out that the representatives of religious minorities and educationists from across Pakistan are also upset with the Single National Curriculum. “Is this what a consensus looks like?”

Jacob also criticizes the government for involving independent consultants for the drafting of new curriculum. “Rather than entrusting the task to experts and senior bureaucrats, the government hired freelance consultants who were accountable to no one,” he says.

That at least some people involved in the process were not competent enough was made obvious by an awkward, though also a funny, revelation that showed a member of the official curriculum review committee objecting to the absence of head gear in what he perceived as a woman’s image in a textbook. It was, in fact, a photo of renowned scientist Isaac Newton.

A speech contest

Maria Richards* is a master's student at a church-owned institution of higher learning in Lahore. Recently, she was helping her seven year old niece study at home during a school closure caused by the corona pandemic.

“Where do we live?” Maria asked the little girl.

“We live in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.”

“Who are we?”

“We are Muslims.”

Maria was shocked. She tried to explain to her niece that both of them were not Muslims but Christians but the girl continued to insist that her teacher had taught her that Pakistan was a place where only Muslims lived. Maria did not know how to explain to her niece that not all Pakistanis were Muslims and that local Christians were as Pakistani as local Muslims.

Some further exploration revealed to Maria that her niece was so indoctrinated at school that she did not even see Christianity as a true religion. Her teachers had told her that Christians had distorted their religion and that Islam was the only true religion in the world. “If this is not hate speech then what is?” Maria asks.

This type of hostility towards non-Muslims is, in fact, rampant in Pakistan, argues Bari. To cite an example, he points to the Tahaffuz-e-Bunyaad-e-Islam Act (the protection of the foundation of Islam act) that was passed by the Punjab Assembly last year to legitimize large scale censoring of books and other publications on religious grounds. “I do not think any curriculum making in such an environment can be progressive,” he says.

This environment of religious intolerance, at least in part, is the reason why the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) has moved the Supreme Court of Pakistan against the Single National Curriculum. It has contended that the new curriculum does not comply with Article 22 of the constitution which states that every citizen has the right to “profess, practice and propagate his religion”.

HRCP has also cited in its petition what is generally known as Justice Jillani Judgment. Named after the Chief Justice of Pakistan who penned it, this July 2014 verdict by the Supreme Court marks a watershed as far as the rights of non-Muslim Pakistanis are concerned. Referring to education, it says: “Appropriate curricula be developed at school and college levels to promote a culture of religious and social tolerance.”

But the government’s response to the HRCP petition has been evasive at best. Instead of answering questions being raised about the discriminatory and non-exclusive nature of the curriculum for general subjects, it congratulated itself for doing something that was not even mentioned in the petition. “In line with the spirit of Article 22 (1) of the constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Curriculum for the subject of ‘religious education’ for five religions including Christianity, Hinduism, Sikhism, Bahai and Kailasha communities has been developed, approved and notified for the first time in the history of Pakistan. Previously, the students from minorities studied ‘ethics’,” the ministry stated.

It, however, offered only platitudes while responding to the criticism the new curriculum has generated. It said the government has ensured that new textbooks do not humiliate, or spread hatred against, any religious minority. It also told the court that no child would be forced to study religious content not pertaining to his or her religion.

A ministry official subsequently explained to the court that those students could sit out if a lesson not concerning their religion was being delivered. A.H. Nayyar believes this to be a highly flawed approach.

Firstly, he says, the students from minority community will have to sit outside the class even while studying essential subjects because these too are replete with Islamic contents. “This will compromise their learning skills,” he says.

Secondly, he argues, this will perpetuate ‘otherization’ that students from minority communities already face in schools. “By having to leave the class every now and then will alienate and stigmatize them further.”

In one of its recent hearings, the Supreme Court also rejected the ministry’s report and asked it to submit a comprehensive rejoinder to the objections raised by the petitioner.

Outside the courtroom, however, a vociferous campaign has been launched against the petition. A digital pamphlet doing the rounds on social media warns Islamic religious circles that an “adverse decision” by the Supreme Court will make it easy for secular and human rights lobbies to have Islamic ideas and religious concepts thrown out of textbooks. The writer of the pamphlet also calls upon the Supreme Court to “become a party” to the petition and present its point of view strongly in the light on the “constitution of Pakistan, the ideology of Pakistan and the Islamic way of life”.

Similarly, Sirajul Haq, the chief of Pakistan’s oldest Islamist party, Jamaat-e-Islami, has issued a statement calling the petition “an international attempt to liberalize and westernize Pakistan”. He said his party would never accept the promotion of liberalism and westernization under the cover of an equitable national curriculum.

All this public hostility towards calls for making the national curriculum equitable for Pakistanis of all religions does not deter a Christian member of Punjab’s cabinet, Ijaz Augustine Alam. He remains adamant that the government does not need a Supreme Court verdict to ward off threats to the rights of non-Muslim Pakistanis in education sector. He insists the government already possesses the power to raise ample safeguards in this regard.

As Punjab’s minister for human rights, interfaith harmony and minority affairs, he has tried to apply some of these safeguards. “We have worked with textbook boards to remove hate material from more than 180 textbooks in Punjab,” he says and claims that every textbook to be published in the province has to pass the scrutiny of his ministry.

What he does not mention is that the associations of Islamic seminaries and the prime minister’s advisor on religious affairs, Tahir Ashrafi, both have taken exception to his efforts. They have asked the government publicly to withdraw the guidelines that his ministry has issued to the Punjab Textbook Board.

And, taking note of their complaints, the provincial government has done exactly that: On April 26, 2021, it withdrew its notification that had recommended the omission of Islamic content from subjects other than Islamiyat. The official move came about after a group of Muslim religious leaders and opinion makers met Punjab Governor Chaudhry Mohammad Sarwar and conveyed to him what they called the public’s concern over the matter.

*Name has been changed to protect identity

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 21 May 2021, on its old website.

Published on 20 Apr 2022