A government report prepared three years ago on Punjab’s sole Violence Against Women Center has not been made public even now because of its damning findings.

Commissioned in the winter of 2018, the report sought to review the performance of the center set up in Multan. Fauzia Viqar, former chairperson of the government-run Punjab Commission on the Status of Women, assigned a team of independent researchers to prepare it. Titled Special mechanisms to address violence against women in Punjab: A study of model gender-based violence court in Lahore and Violence against women center in Multan, it was completed in early 2019.

But then Viqar’s tenure at the commission came to an end the same year and the report was never made public. She is distressed to know that it has not seen the light of the day yet and believes that “it could have been shelved because of its contents”.

The report’s lead author, Sohail Akbar Warriach, who works as a consultant at Shirkatgah, a women’s rights organization based in Lahore, says the process of censoring it started before someone at the commission decided to dump it altogether. He says when he received a digital copy of its pre-printing version, he found out that it did not include any findings about the Violence Against Women Center.

He, nevertheless, released a digital version of the incomplete report through Shirkatgah’s website.

Officials at the Punjab Commission on the Status of Women are either unaware of what happened to the report after it was written or they feign ignorance about it. Imran Javed Qureshi, a senior lawyer posted at the commission, says it has been working without a chairperson for the last three years and it does not have enough money even to run its offices. So, he says, it has not had any technical resources to manage any content it has generated over the last three years. “The report might have been left unpublished due to that reason,” he surmises.

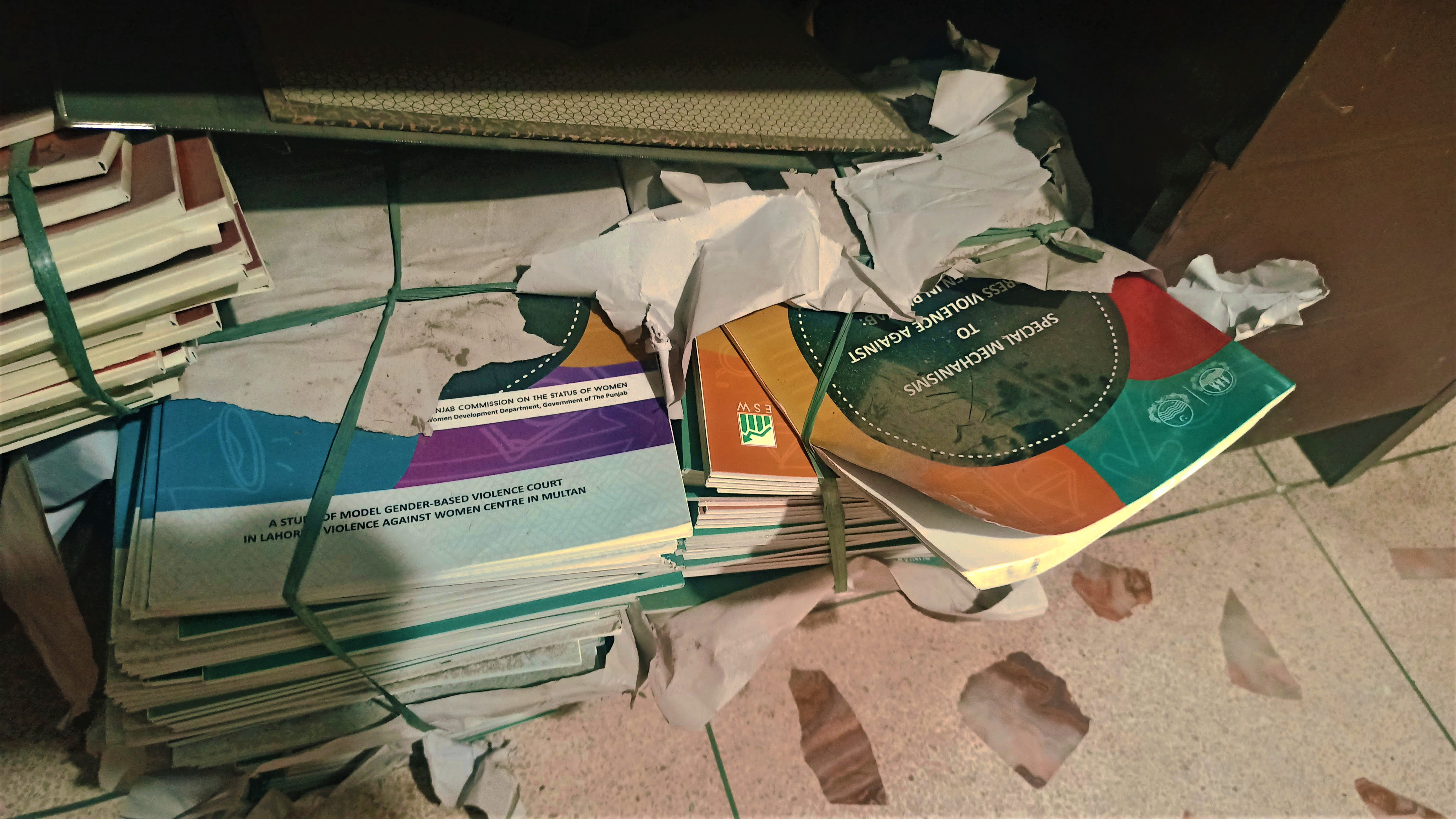

Unbeknown to him and most of his colleagues, however, several hundred copies of the report printed on a fine paper are lying in wrapped bundles in a room next to where he sits. It is not certain if these copies contain the chapter about the center but what is confirmed is that they have never been distributed to anyone.

Ugly truths

Violence Against Women Center was set up under a law, Protection of Women Against Violence Act 2016, which also provides for the establishment of Punjab Women Protection Authority. The law gives the authority the power to “establish, maintain, monitor, govern, operate and construct” such centers across Punjab to protect women from violence.

Printed copies of the VAWC Multan's evaluation report present in Punjab Commission on the Status of Women, Lahore.

Printed copies of the VAWC Multan's evaluation report present in Punjab Commission on the Status of Women, Lahore.The unpublicized report says the provincial government inaugurated the center on March 25th, 2017 – but without so much as issuing a notification for the formation of the authority which eventually came into existence in 2019. In the intervening period, Strategic Reform Unit (SRU) of the Punjab government took over the task of running the center even when it did not have any legal authority to do so. Salman Sufi, who headed SRU under former chief minister Shahbaz Sharif in 2013-2018, admits that “many bureaucratic procedures were bypassed to enable it to work.”

This bypassing of legal procedures created more problems than it resolved, says the report. To cite just one example, SRU issued a notification on September 26th, 2017 and appointed five Multan-based lawyers, including a woman, to work at the center. They were assigned the task to handle -- in collaboration with the Punjab prosecution department – cases of violence against women. Their tenure lasted only around three months – that is, till the end of December 2017 – and then no lawyers were hired over the next whole year or so, says the report.

It also reveals that the police station set up in the Violence Against Women Center has been operating without any clear Standard Operating procedures (SOPs). The two draft versions of these SOPs, prepared by the Regional Police Office Multan between March 2017 and August 2017, are vastly different from each other, the reports says.

It, therefore, doubts the center’s ability to meet its objective of expediting the trial and punishment of those involved in committing violence against women. Not a single conviction happened in the first two years of its operations, the report notes.

On the contrary, the center dropped a large number of cases – including nine that involved rape allegations, it points out. This “raises questions about why the staff at the [center’s] Police Station is allowing compromises to take place” in such cases or letting the victims or their families to withdraw them.

The authors of the report also found the police station to be headed by a female sub-inspector answerable to a Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) even when the law says it must be headed by a female inspector answerable to a female Superintendent of Police (SP). They, similarly, allege that police officials posted at the center were not aware of the sensitivities of gender-based violence. Their approach, therefore, was “not conducive to the type of cases they have to handle”.

Warriach recalls how the center’s sub-inspector accused rape victims of being complicit in violence committed against them. “I don’t know how many times they get themselves raped before they come to us,” is what she said to him in her interview.

Different approaches, different outcomes

Even now there is little clarity about the scope, functions and jurisdiction of the Violence Against Women Center and the police station it houses. Similarly, the appointment of its staff – doctors, lawyers, prosecutors, psychiatrists and laboratory assistants – has not been completed even though five years have passed since its inauguration.

Also Read

Victim of neglect: Multan's center for helping women in distress fails to achieve its objective

Its critics point out that there is a similar confusion about how the cases of violence against women are to be registered and handled there. They ask: Does each such case surfacing anywhere within the territorial jurisdiction of Multan district needs to be registered only at the center’s police station? This, according to them, will not be easy for poor and illiterate women living in far-flung villages as they will have to travel all the way to Multan to get their case registered. So, they ask, should a case then be registered at the police station nearest to a victim before it is transferred to the center for investigation and prosecution? This, in their opinion, seems to defeat the very purpose of having a police station within the center because one of the basic premises of setting it up has been to save the victims from the problems they face in convincing the police to register their cases.

Hiba Akbar, a Lahore-based lawyer who has co-authored the unpublished report, says the main reason for all these ambiguities is that the provincial government has not yet prepared and notified rules and regulations required for the implementation of Punjab Protection of Women Against Violence Act 2016. Making a law alone was never going to address the centuries-old problem of violence against women, she argues.

She also says the law itself was drafted and enacted hastily. “It was passed as a ‘quick fix’ solution without ensuring that it was accompanied by all the institutional arrangements required for its effective implementation.”

Contrary to her holistic approach, Sufi is fine with the current piecemeal policy. He, therefore, says the report might have been censored so that it did not damage the center before it finally starts delivering. “It takes time to build and strengthen such institutions,” he says.

Published on 30 Apr 2022