The two women knew their rapists and yet they did not pursue cases against them.

One of them – Shazia Bibi – is a resident of Todar Pur village in Shujaabad tehsil of Multan district. She accuses her deceased husband’s younger brother of raping her multiple times between June 13th, 2020 and August 13th, 2020. Sitting on a tumble-down charpoy in her two-room dilapidated house early this year, she says she could not have him tried because she did not possess the means to do so.

A lean, dark-skinned woman, she is only 35. A widow for the last four years, she has two daughters – aged eight and nine – and a son who was born around the time his father passed away.

She says her brother-in-law, Amir, who lives in the house next to hers, would lock her in a room where he would rape her at gunpoint while his accomplice, a woman named Shabana, took her photos with a mobile phone. When she became pregnant, she stated in a complaint that she filed at a police station in Shujaabad town on August 24th, 2020, Amir and Shabana forced her to take injections and other medicine to get rid of the fetus.

She also alleged in the complaint that Amir threatened to upload her pictures on the internet if she ever told anyone about her rape. He warned her that he could harm her children too if she chose to reveal her ordeal to anyone, she says.

Shazia Bibi's house in Todar Pur village

Shazia Bibi's house in Todar Pur village This, according to her, is the reason why it took her more than two months to report her rape to the police. She says she could get out of her house to reach the police station only after some people came looking for Amir and he had to be away from her house to avoid them.

This, she stated in her complaint, gave her the opportunity to reveal her ordeal to her fellow villagers who had gathered in her house at that time due to the hue and cry she raised. Their presence made Amir and Shabana disappear from the village, she says.

Around 16 months later, Shazia’s father, a tall man with a white beard and wrinkled face, is sitting despondently in his house at Todar Pur.

He says his clan’s elders have persuaded him and his daughter to withdraw the case against Amir and Shabana. He shows an empty stamp paper given to him by the two accused in January 2022 so that he can write anything in it against them if they ever trouble her daughter again.

The paper, obviously, has little legal utility. Amir and Shabana can easily deny having given it to Shazia’s father or having given him the authority to fill it in with the contents of his choosing.

Shazia, though, points out that, even in the absence of the stamp paper, she was faced with a Hobbesian choice: “Should I run after Amir and Shabana to get justice or feed my children?”

She owns a small piece of land on which she grows vegetables that she then sells to earn a meager living. Although she also milks her neighbors’ cows to make some additional money, she still cannot afford to bear the legal expenses of her case.

Victim blaming?

The second woman, Irshad Bibi, is also a resident of a Shujaabad neighborhood. Her 42-year-old mother Haseena Bibi made an emergency call at 15 – the police helpline – on July 9th, 2020 asking policemen to reach her house immediately. She told them on the phone that a man had broken into her house and was trying to rape her 19-year-old daughter.

Before the police arrived, some local residents, alerted by Haseena Bibi’s cries for help, had gathered at her house and had reportedly found one Muhammad Rizwan inside it. The police later arrested him and took him to a police station in Shujaabad.

According to Haseena Bibi, they also took hold of his shoes (that he had taken off before entering her house) and a ladder that he had allegedly used to climb into her courtyard.

She, too, was asked to be at the police station. When she reached there, however, she was told to wait because the officers there were busy. Then she was asked to come back later. The police, she alleges, kept delaying the registration of her complaint under various pretexts.

In the meanwhile, she says, Rizwan entered her house again on July 28th, 2020 – along with three other people. Carrying axes, she alleges, they beat up her son and nephew and told them not to proceed with the case otherwise they would burn her face and that of her daughter with acid. She went to the police again and asked them to register her complaint but, she says, they refused to do so.

So, on August 17th, 2020, she moved a local court in Shujabad for the registration of a First Information Report (FIR) against Rizwan. The court accepted her plea on August 27th and ordered the police to register the FIR. The police complied with the court order on August 27th -- 49 days after the incident had taken place.

Nine months later, however, the court of Amjad Khan Mukhtar, an additional sessions judge in Shujaabad, acquitted Rizwan of all the charges. He said in his verdict issued on May 19th, 2021 that only Haseena Bibi and Irshad Bibi were in a position to identify the accused but they refused to do so in their testimonies. The latter, in fact, testified that the man who had assaulted her was hiding his face in a muffler.

District prosecutor's office in Multan

District prosecutor's office in MultanThis, though, is not the only case of this kind. The data gathered from the same court shows that the complainants withdrew their allegations in five of the 12 cases of sexual assault that Mukhtar heard in 2020-21. In one of these cases, State vs Abdul Ghaffar, for instance, the accused submitted a “letter of innocence” written by the victim. In another, State vs Nasir Hussain, the victim gave a statement in the court that she has forgiven the main accused.

It is on the basis of such cases that Qaiser Abbas, a government prosecutor based in Shujababd, argues that even the confirmed rapists cannot get punished because their victims reconcile with them. “Most of the women subjected to sexual assault in this area are very poor so they are highly susceptible to being pressurized into reconciliation. This explains why most of them do not pursue cases against their tormentors,” he says.

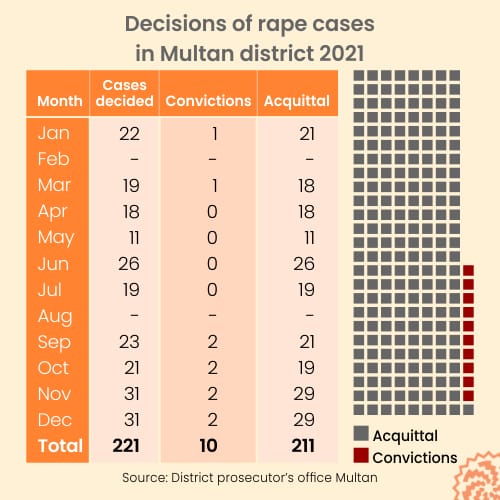

This is corroborated by a report sent recently by the district prosecutor’s office in Multan to Punjab’s Prosecutor General. It states that victims reconciled with perpetrators in four out of 11 cases of sexual violence prosecuted in Multan in November 2021 alone.

Rana Ayub, another prosecution official in Shujaabad, has a theory to explain this phenomenon. According to him, the reason why victims reconcile with perpetrators in such large numbers is because most allegations of sexual assault are fake to begin with. “I cannot understand why a woman who has been subjected to such a horrific crime would withdraw her case without much ado,” he says.

Officials in Multan’s district prosecution office also echo his contention. Pointing to the fact that conviction rate in rape cases in the area under their jurisdiction remains as low as 4.5 percent, they claim that this is because most such cases are not genuine. One of them goes to the extent of explaining the parameters which, according to him, make a case fake. These are:

- The victim claims to be virgin but her hymen examination suggests otherwise

- The victim does not report the crime immediately

- The victim’s body carries no signs of resistance against rape.

These parameters, in his opinion, suggest that the alleged rape was, indeed, an act of consensual sex. When confronted with such a case, he says, “we do not make a serious effort to pursue it because we know that the parties involved in it will reconcile with each other sooner or later”.

Falling through the cracks

Umer Farooq Khan works as a deputy district prosecutor in Multan. Unlike his colleagues quoted above, he believes that faulty investigation by police is to be blamed for a low level of convictions in rape cases. In most cases, he says, the police fail to complete the indictment process on time while in many others, they do not collect DNA samples in a timely and accurate manner. “They also do not use modern technology like videos of the crime scene to put together evidence.”

To prove his point, he cites an ‘adverse outcome’ report sent by his office to the Prosecutor General’s office in Lahore. It carries 1,000 objections that prosecutors have raised over police’s investigations in cases of sexual violence registered in Multan in 2021, he says.

Also Read

The cross on their little shoulders: Kidnapping and forced marriages of Christian girls in Pakistan

The police, in turn, blame courts and the victims of sexual violence for the low rate of convictions. Khurram Shehzad Ahmed, Multan’s district police officer, says most cases drag so long in courts that many victims fail to muster energy, time and financial resources to keep up with them. He also blames victims for “succumbing under pressure” and for “taking money from the other side”. Consequently, he says, they do not cooperate with police which impacts the investigation “significantly”.

Women rights activist and rape victim Mukhatar Mai, however, disagrees with him. Rejecting his claim that a rape victim reconciles with her tormentor voluntarily after taking money or getting some other benefit, she says: “There is a lot of shame attached to being a rape victim.”

Particularly in southern districts of Punjab, that include Multan, “raped women believe that they have lost all their honor and respect in the society”. In such circumstances, according to her, they never want to be seen as being soft towards someone who has deprived them of that honor and respect – unless they have no other option.

So, she contends, if and when they reconcile with the accused, “they do so because they find themselves at odds with the system -- unable to match the power of their adversaries”.

Published on 3 Mar 2022