Saqib William left his home in 2016 and never returned.

Before his disappearance, he was living with his wife, Ruth Nathaniel, and three little daughters, Hania, Tania and Sania, in a two-room lodging in Iqbal Abad, a working class neighborhood in Karachi. After he left, Ruth could not afford to stay in that house so she took her daughters with her to live in Shanti Nagar, a predominantly Christian village near Khanewal city.

Her two brothers have a small house there. Her marriage with Saqib had also taken place there in January 2012 at a Salvation Army Church before she moved to Karachi with him.

Four years later, when she came back to Shanti Nagar, her brothers started searching for Saqib. Unable to find him, they landed upon some unexpected information: He had been married twice – including with a Muslim woman -- before marrying their sister.

Saqib’s first wife was a Christian woman named Shaista Masih. They got married in 2002 in Karachi and had two sons and a daughter together. He then converted to Islam on 14th February 2009. In his conversion certificate, he stated that he had invited Shaista to convert as well but she did not accept that invitation. So, he declared, his marriage with her was over.

In the same year, he contracted a Muslim marriage with a woman named Shabana. In his marriage deed (nikahnama), he put down his name as Muhammad Saqib. Three years later, he divorced Shabana and married Ruth.

As if all this was not horrific enough for Ruth to know, Saqib sent her an affidavit on an official stamp paper on 3rd December 2019. It showed that he had converted to Islam again and, therefore, had nothing to do with her anymore. Soon afterwards, he married another Christian woman.

How could Saqib have four marriages given that Christian men are obligated by their religion to have just one wife at a time? A recently passed law also provides that no Pakistani man, regardless of his religion, can have a second wife without the explicit permission of the first.

One possible answer lies in the fact that the Christian Marriage Act, passed in 1872, does not provide for a governmental registration of Christian marriages. Consequently, these marriages are registered only at local churches with no centralized record. This often allows Christian men – and also women – to hide their earlier marriages while remarrying.

Shehzad Francis, a Christian social activist based in Khanewal, says religious restrictions on the number of marriages cannot be enforced without a formal marriage registration system. “A married man can simply go to another city and contract another marriage by declaring himself a bachelor,” he says. “The bride’s family would never know that he is lying and the priest solemnizing the marriage would never bother to do background checks,” he says.

The other problem caused by the absence of a government registration system is that women like Ruth cannot sue their husbands for alimony. As Francis explains, a major hurdle in their way is the fact that they do not have a government-approved document to show that they are legal wives of those men.

He, as well as many other human rights activists belonging to Christian community, therefore, demand that the Christian Marriage Act be amended to provide for a mandatory and centralized system for registering Christian marriages.

And that, they say, is not the only amendment that the law needs. As Sabir Michael, a Christian social activist and teacher based in Karachi, says: “This law states that a wedding has to happen before sunset because it was not safe a century and a half ago for marriage parties to travel in the night whereas most marriages now take place in the evenings”. He also points out that the act permits the marriage of girls as young as 13 years of age. “This is a violation of international conventions on women’s rights and also flies in the face of Pakistan’s own laws against child marriages.”

These activists similarly argue that the Christian Divorce Act, promulgated in 1869, is hurting Christian women disproportionately. Under this law, the only way for a Christian woman to get divorced from a violent husband is to prove that he is having a sexual relationship with another woman. If she cannot prove that, she might have to suffer torture and abuse at the hands of her husband all her life. Or, as is the case with Ruth, she might have to suffer life-long loneliness with the additional burden of having to raise her children.

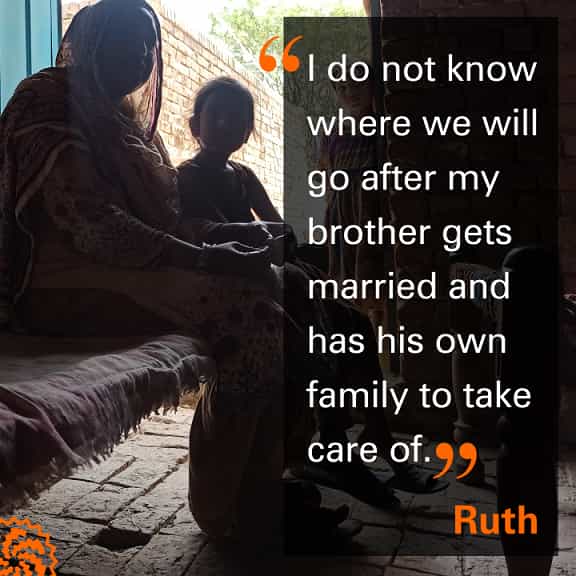

Wiping sweat from her forehead, she fans her daughters with her dupatta on a hot summer day and insists that she will never seek a divorce because that is against her religious beliefs. “I want to live with my husband,” she says, “but what do I do if he does not want to live with me?”

Short of his return, Ruth wants to secure maintenance money from him so that she can raise her children without having to depend on anyone. She lives in a cramped featureless room within the house her brothers own and often goes without eating. “Only one of my two brothers is employed as a laborer. His earnings are barely enough for all of us to make ends meet,” she says.

Even that source of money is not going to be there for her forever. “I do not know where we will go after my brother gets married and has his own family to take care of,” she says dejectedly.

Paperless marriages

Sarah was still not born when her father left her mother, Nasreen, around 12 years ago.

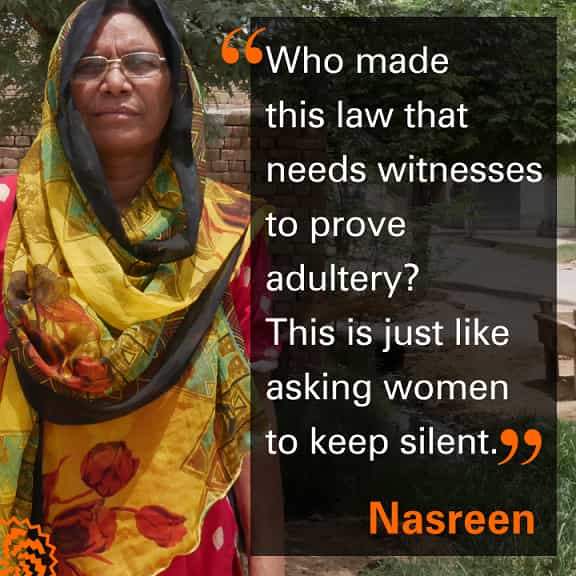

Nasreen says he was never loyal to her. “He would flirt around with my younger relatives and I hated that,” she says. But she did not know how to prove his adultery to get a divorce from him because that required her to produce witnesses who had seen him do that. “Who made this law that needs witnesses to prove adultery?” she asks. “This is just like asking women to keep silent.”

Iftikhar Alam Adeem, a local politician and chairman of Shanti Nagar union council, argues that a law that makes it easy for Christian couples to leave each other without resorting to the allegations of adultery has become the need of the day. The absence of such a law is forcing people to seek all kinds of quasi-legal and even illegal ways to leave their spouses, he says.

Many of them become Muslims because that annuls their Christian marriages automatically. “Many others ask me to countersign affidavits that announce unilaterally that they are ending their marriages,” he says.

Adeem keeps telling them that these documents have no legal validity but they “still go ahead with preparing them because they believe that this is the closest thing to making their divorce official,” he adds.

Nasreen also demands that women whose husbands leave them must be provided with a formal legal right to end their marriages. In the absence of that right, she says, “a man does what he wants and when he wants and a woman cannot even raise her voice against him”.

She lives with her brother in Shanti Nagar in a small room that has no furniture except a broken bed. The only utensils she has – a few plates, two cooking pots, a water-cooler – are lining a mud-plastered wall in her room. A small gas cylinder fitted with a cooking stove is also lying in a corner.

Nasreen does not get any money from her husband. She also does not have any financial resources to move a court against him to demand alimony. Her brother does not like this situation. “My uncle does not treat my mother very well. He thinks we are a burden on him,” says Sarah.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 29th June 2021, on its old website.

Published on 16 Feb 2022