Muhammad Manzoor could see his face in the clear waters of the river Ravi 32 years ago. He would sometimes bathe in it and perform ablution and wash dishes with it too. He has also seen people drinking water straight from the Ravi.

Muhammad Manzoor has been rowing a boat on the Ravi for the last four decades. Most of his passengers come from Lahore. They want to visit Kamran’s Baradari, a Mughal-era historical monument situated in the middle of the river.

On a recent day, Muhammad Manzoor is bargaining with tourists desirous of visiting the Baradari. He is sitting in a makeshift ticketing cabin made of iron rods and cloth sheets. He is wearing a white cap and a cream shalwar kameez and looks more like a religious preacher than a boatman. His white beard makes this aura of religiosity even more palpable.

Large swathes of sand can be seen in the almost dry riverbed from his ticket cabin -- with a thin stream zigzagging through it. Its slow pace makes the river look like an elongated pond.

The people going toward Baradari have to walk several hundred meters on the dry and sandy riverbed to reach where several colourful boats are anchored. The river, indeed, is so shallow that it can be crossed on foot but the visitors prefer to travel by boat as they do not want to get their clothes wet with its stinking and dirty water.

As soon as their journey starts, they encounter an unbearable smell coming from the river’s blackened waters. Although Manzoor and other boatmen are used to this smell, he still says: “Our sense of smell has been affected so badly by this foul odour that we cannot feel any smell or taste in any kind of food.”

Swarms of mosquitos can be seen hovering above the river's surface. One can also see several buffalos drinking water from the river. Manzoor says “these buffalos drink this polluted water and then we drink their milk”.

Blast from the past

The Ravi is one of the six rivers that originate from the Himalayas and enter Pakistan after flowing through Kashmir and northwestern parts of India. It flows into Pakistan at Kot Naina, a village in Narowal district in Punjab. After travelling another 675 kilometres, it joins the river Chenab that, in turn, becomes Punjnad at a place in the western part of Bahawalpur district where five rivers meet – before flowing into the River Indus.

According to the renowned Indian historian Professor Irfan Habib, there was a time when ships plied in the Ravi. In his book, Shahenshah Akbar, he quotes Mughal emperor Akbar’s vizier Abul Fazal as saying that “in 1594, Akbar himself inaugurated the construction of a large vessel at the bank of the Ravi”.

This ship was so big that it took one thousand people to push it into the river. It then travelled in the Ravi, the Chenab and the Indus to reach Thatta harbour where another ship took its passengers to Makkah through the Red Sea.

In 1876, during the British era, Ravi’s water was so clean that the British used it to provide drinking water to Lahore. They brought the river water into a large pond built near the Fort and supplied it to the whole city. This pond is still there – at the juncture of Kashmiri Bazaar and Heera Mandi – and its location is called ‘Pani Wala Talaab’ (or water pond) even today.

Muhammad Manzoor, too, remembers the better times that Ravi has seen and says: “In the past, this river was a very good place for recreation. It had many varieties of water hens, migratory birds and fish. We would catch big fish – sometimes weighing as much as 18 kilograms – from its waters.”

According to him, the river was both very wide and very deep till about 30 years ago. “Its depth would be anywhere between 18 feet and 22 feet. Students from the Government College, the Punjab University and other educational institutions used to get rowing training on the Ravi,” he says and laments the fact that all this has become a forgotten tale since the Ravi has shrunken from a river to a sewage-strewn stream.

According to a report by the Asian Development Bank, water flow in the Ravi in dry weather is recorded only at 10 cubic meters per second. Even in the rainy season, this flow does not exceed 10,000 cubic meters per second which is lower than the flow of some major canals in Pakistan.

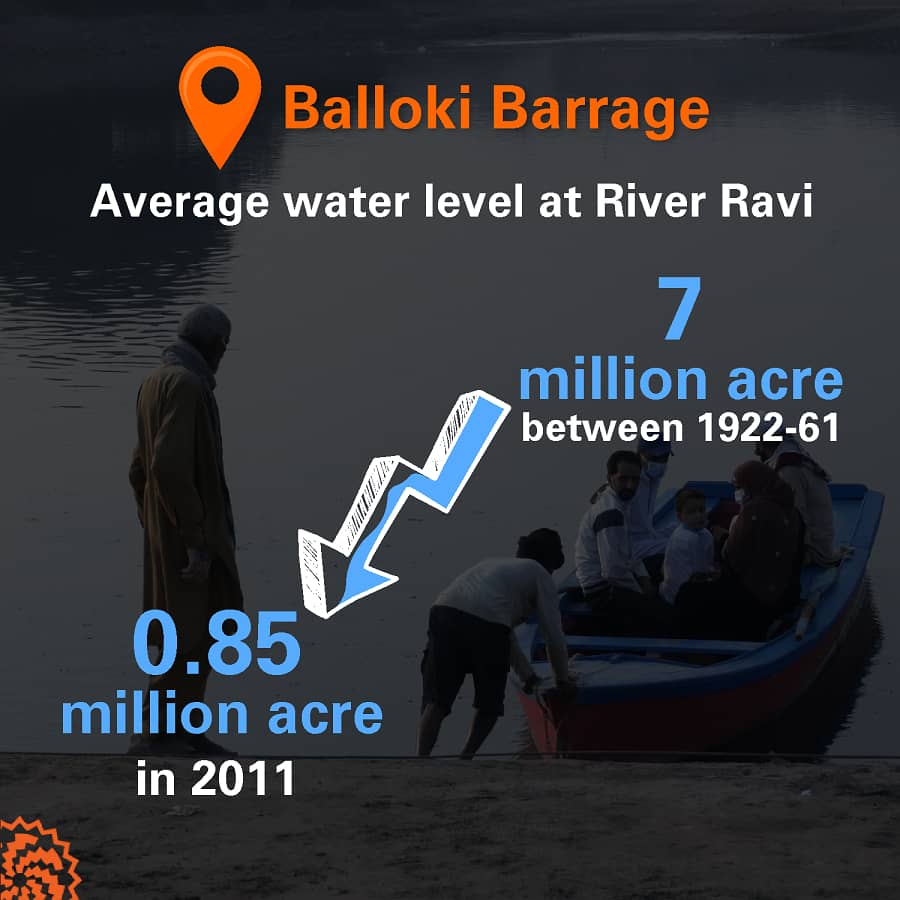

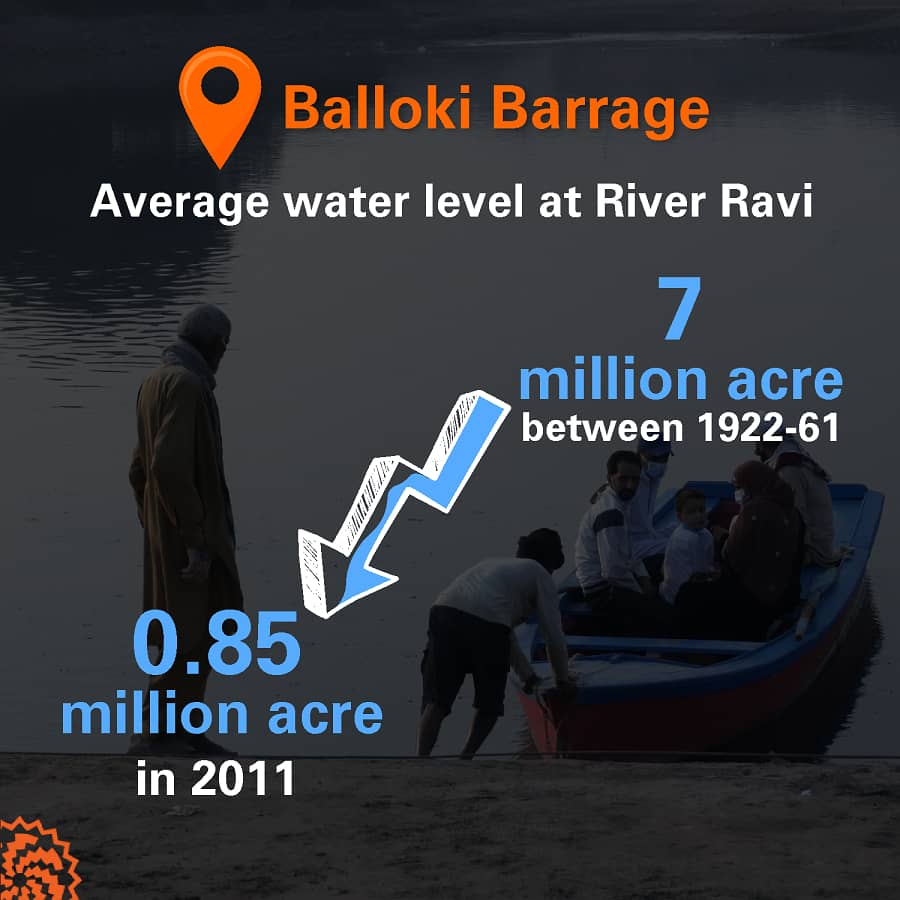

The severity of water shortage in the Ravi can also be measured from the fact that the average water level at Balloki Barrage – located 62 kilometres downstream from Lahore – was seven million acre feet between 1922 and 1961 but it had come down to 0.85 million acre feet in 2011.

Death of a river

Garbage, untreated urban waste water and poisonous industrial and commercial effluents have been contaminating the river for the last three decades. A report published by the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) states that 2700 industries set up in Lahore discharge their untreated waste water directly or indirectly into the Ravi. All the untreated waste water generated in the city’s southern industrial areas – the ones located on Ferozepur Road and in Sundar – goes into the Ravi through various drains and sewerage lines. Likewise, poisonous chemicals discharged from metal foundries and other industrial units located in the northern parts of the city also become a part of the Ravi.

A huge amount of human waste, too, is mixing in the river. To measure it roughly, consider the fact that every inhabitant of Lahore, according to a report released by the city government’s Water and Sanitation Agency (Wasa) in 2013, produces 231 liter of liquid waste every year. Given Lahore’s population of 11 million people (as recorded in 2017 Census), the whole city is producing nearly 2.5 billion liter of liquid waste every year -- which is mostly going into the Ravi.

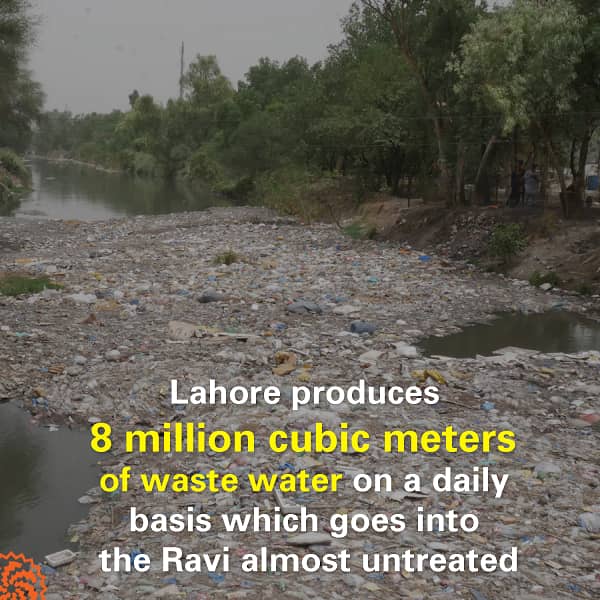

The Japan International Corporation Agency (JICA), an organization delivering aid to third world countries, similarly released a report in 2010 which states that Lahore produces eight million cubic meters of waste water on a daily basis. A lot of this water goes into the Ravi untreated because Wasa’s 12 pumping stations located at various parts of the city can handle only 5.7 million cubic meter waste water on a daily basis. Even these stations do not have the capacity to remove chemicals and bacteria from this water so the quality of the water passing through them before getting into the Ravi is only marginally better than that of the water being discharged directly into the river.

Another major contribution to the river’s pollution is coming from 14 large drains which are always choc a bloc with all types of domestic waste which they eventually vomit into the Ravi.

All the waste mentioned above is polluting not only Lahore’s underground water but also affecting the Ravi’s aquatic life. A WWF report reveals that 42 species of fish have disappeared from the Ravi because of this pollution.

Dr Kausar Abdullah Malik, the dean of Postgraduate Studies at the F C College University, recently headed a commission established by the Lahore High Court to recommend ways and means to the Punjab government to cleanse the river. In his opinion, “river pollution affects everything related to the river water. For example, we were used to hearing frogs croak during every rainy season but now these sounds have disappeared because water bodies necessary for the survival of frogs are drying up rapidly”.

Rafay Alam has similar views. He is known as an expert on environmental law and it was on his petition that the Lahore High Court set up the commission on the Ravi of which he also became a member. He says: “There is no water left in the river. All we see is a liquid full of poisonous substances.”

Pollution has turned the Ravi into a dead river where nothing can survive. Not just that. Its polluted water carrying poisonous metals and chemicals is mixing up with the food chain and causing the death of fauna and flora at a large scale.

Dr Imdad Hussain is especially worried about the river pollution’s effects on birds and aquatic insects living in and along the river. He teaches urban planning at the F C College University and has participated in several research activities related to environmental subjects. While talking about the Ravi, he waxes nostalgic. “If you watch PTV’s old dramas recorded at the Ravi, you can see so many birds flying in the sky above the river. You can see even their nests on the trees at the river bank,” he says and mourns that these birds no longer exist. “Instead, you only see vultures and crows flying above this ‘dead river’. Waste water has strangulated life in the Ravi’.

Dr Imdad Hussain also says that aquatic life – including insects -- plays an important role in maintaining the nature’s environmental equilibrium though we still do not know much about this role. “The terrain alongside a river also contains many kinds of shrubs, herbs and plants which are essential for preserving the earth’s biodiversity but we have never tried to save these plants so many of them have become extinct.”

Contamination of underground water

In 2017, the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR), a Lahore-based government organization, and WWF Pakistan cohosted a meeting in which experts revealed that underground water in Lahore is depleting at a rate of three feet per year. This is mainly because we are drawing this water at a very rapid pace with tube wells and electric motors. The situation has become so dire that underground water in central Lahore can only be found at the depth of 130 feet. Experts also warn that underground water level in the city could go down to 230 feet in the next five years.

The main source of recharging this underground water table is the Ravi which has very little water in it. If nothing is done to revive the river, experts fear, Lahore will face severe shortage of drinkable water in the coming decades.

Dr Kausar Abdullah Malik is concerned that whatever little recharging of this underground water level is being done by the Ravi is harming the water aquifer more than helping it. “The polluted water of the river is contaminating the underground water reserves with poisonous chemicals and metals. If we do not decontaminate the river’s water urgently, it will destroy our underground water resources on a permanent basis.”

Dr Imdad Hussain agrees and says: “Drinking water in settlements nearby Ravi is malodorous and has a dirty pale colour.”

At many places in central Punjab, people are using this filthy water for all kinds of purposes. For instance, it is being used for agriculture in Lahore and Faisalabad divisions with the result that crops, vegetables and fruits grown with this waste water carry dangerous levels of poisonous substances such as cadmium.

Also Read

A recipe for disaster: How Ravi River Front will harm the ecology of a dying river

It was in view of this situation that, in 2012, the Lahore High Court set up a commission to examine -- and find a solution of – the waste water mixing up with the Ravi. The court advised the commission to complete its work within two months.

The commission suggested that an inexpensive technology should be deployed to clean the river water. It, therefore, proposed to plant a floating island of vegetation and spread certain bacteria into it so that it could move around the Ravi and absorb poisonous substances mixed with it. The project was estimated to cost 500,000 US dollars at that time.

But, as Rafay Alam says, “this project was never implemented because no governmental department was ready to take responsibility of starting and running it and the government at that time also announced to build a modern, glittering, city on the river itself. “So the provincial authorities started opposing our suggestion, saying that our little project should not stand in the way of their grand plans for the river.”

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 14 Nov 2020, on its old website.

Published on 31 May 2022