A miracle happened in 2017 at an unassuming spot – a garbage dump – in Islamabad. A group of nine Pakistani and Chinese scientists discovered there a type of fungi that can eat plastic.

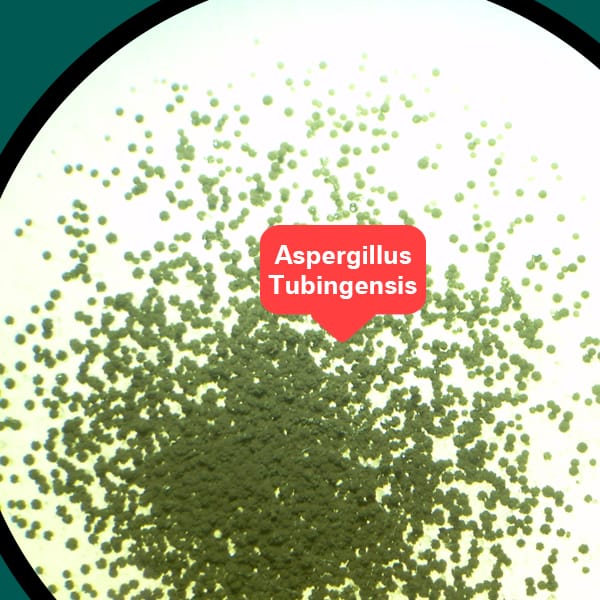

They took samples from the site, located in the city’s H-10 sector, examined them in a lab and found that the fungi, scientifically called Aspergillus Tubingensis, could be helpful in getting rid of the solid waste comprising plastic products.

Their findings were later published in an Amsterdam-based international journal called ‘Environmental Pollution’ as a study titled ‘Biodegradation of polyester polyurethane by Aspergillus Tubingensis’. Funded by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan, the study noted that the mycelium of the fungi, or the network of its threads, occupies the surface of polyester polyurethane plastic – usually used in foam and tyres -- and causes it to decay and decompose.

This discovery, according to Dr Samina Mehnaz, chairperson of the School of Life Sciences at the Forman Christian College University, Lahore, “opens a plethora of pathways to tackle the problem of pollution and waste through natural methods”. She has been teaching biotechnology for the last 10 years and is herself working on a research paper which analyzes different kinds of microorganisms that can be used for eradicating plastic waste and cleaning contaminated water.

She, however, laments the fact that the government of Pakistan has not done anything so far to benefit from the discovery of the fungi in Islamabad.

How the science of it works?

Similar to a wall made up of bricks, a particle of industrially-manufactured plastic is made up of several molecules. These molecules are held together by chemical bonds -- just like bricks in walls are held together by cement. Aspergillus Tubingensis erodes those chemical bonds and, thus, causes the disintegration and decomposition of plastic particles. This fungus is typically found in soil but, unlike most other microorganisms which feed on dead organic matter, it can break down plastic surfaces in a few weeks in order to use them as its diet.

The technique for using fungus for eradicating plastic waste is called bioremediation which essentially reduces pollution through a biological transformation of the pollutants into non-toxic substances. This technique deploys both aerobic microorganisms (which need oxygen to survive) and anaerobic microorganisms (which do not need oxygen to survive) to change the waste into an energy source.

One of the most successful examples of the use of bioremediation is its deployment at the site for London Olympics 2012. That site was heavily polluted with industrial and chemical waste. With the government’s help, some scientists deployed there some microorganisms which are called archaeal and have no nucleus in their cells. They broke down highly toxic ammonia found in underground water at the site and turned it into harmless nitrogen gas.

The River Ravi Commission, set up by the Lahore High Court, also proposed something similar in 2012. Comprising several scientists and environmentalists, it suggested the use of microorganisms to clean the highly polluted waters of the Ravi flowing next to Lahore. They proposed the setting up of a wetland spread over 50 acres of land at Babu Sabu, on the southwestern edge of the city, where microorganisms and plants would be used to rid the river water of the pollutants present in it, says Dr Kausar Abdullah Malik who was a member of the River Ravi Commission. “The aim of building the wetland was to introduce plants such as hydrophytes into the dirty water reservoir,” he says.

Malik, who is dean of the School of Life Sciences at the Forman Christian College University, Lahore, explains that these plants can remain submerged in water throughout their life cycles and can reduce the pollution present in water in two ways: firstly, their roots trap metallic compounds, and secondly, they increase the presence and activities of microorganisms in water which, in return, produce a natural ecosystem that consumes pollutants as a source of energy.

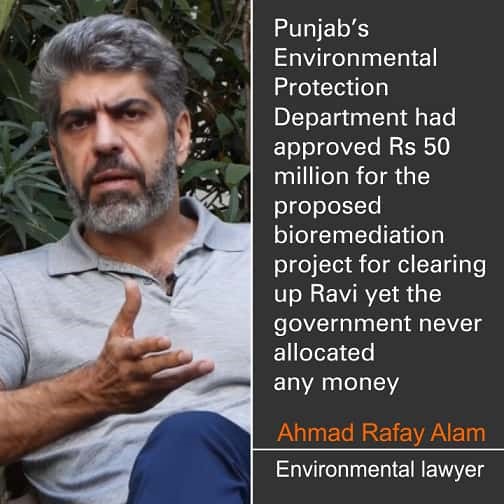

Ahmad Rafay Alam, a Lahore-based environmental lawyer who was also a part of the River Ravi Commission, says the Lahore High Court and Punjab’s Environment Protection Department both approved the proposed bioremediation project for clearing up the Ravi. Its cost was estimated to be a meager 50 million rupees yet the government never allocated any money for it, he says.

Limits apply

A recent study by the World Wide Fund for Nature states that an estimated eight million tons of plastic waste is entering the oceans every year. By 2050, the study warns, there could be more plastic in these oceans than fish.

It also points out that plastics account for 65 per cent of total solid waste being generated in Pakistan. Only one plastic product, polythene bags, is being consumed in the country at an alarming scale: 55 billion of these bags are used here every year and their usage is growing at a very rapid annual rate of 15 per cent.

Decomposition of such huge quantities of plastic is a problem not just in Pakistan but all over the world – more so because plastic takes extremely long to decompose naturally. According to some scientific estimates, plastic products take anywhere from 450 years to 1000 years to decompose in the soil.

This is an incredibly long time. Due to the alarming levels of environmental pollution being caused by plastic, we certainly cannot afford to wait that long.

Scientific communities and civil society organizations, therefore, are proposing various ways and means that can halt the spread of plastic and the pollution caused by it. The use of plastic-eating fungus is just one of the solutions being suggested.

Experts, however, warn that this solution is neither easy to implement nor sufficient to eradicate all plastic pollution.

Dr Sheroon Khan, the lead author of the research study on Aspergillus Tubingensis discovered in Islamabad, says that “finding microorganisms that can eat plastic is not easy.”

Mehnaz, agrees with him. The fungus that can eat plastic, she says, takes a huge amount of painstaking work to even spot. Advanced microscopic technology and luxury to monitor a site regularly over a long period of time are the most essential requisites for finding these microorganisms, she says.

Also Read

Brick by brick: The deadly contribution of emissions from kilns in Punjab to winter smog

This is mainly because of the biological fact that the same fungus growing in different places could have different characteristics. As Mehnaz puts it, several factors affect the capacity of a fungus to grow into a plastic-eradicating microorganism -- the most important of them being temperature, level of acidic materials in the soil and water and the type of physical environment in which the fungus is growing. Any variations in these factors could easily affect its capacity to eat plastic.

Others say the problem is too big to be handled through a single technique. Dr Bryan Cassone, who was a parts of a team of scientists working at the University of Manitoba which found in March 2020 that waxworms could also eat plastic, says: “The plastic pollution crisis is far too big to simply throw these caterpillars at [it],” he said at a press conference.

Waqas Hameed Butt, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Toronto, Canada, who also works on the collection of waste in Lahore, similarly points out that the bioremediation method has its limitations. “While it is extraordinary that scientists are looking for natural ways to deal with the problem of global pollution, these solutions can only be used at a micro level,” he says. “The reason is obvious: when scientists try to scale up these natural methods, they face problems to produce microorganisms at a level larger than they could manage within their labs,” he says.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 21 Jun 2021, on its old website.

Published on 11 Jun 2022