Hudiara is a small village on Barki Road, on the eastern outskirts of Lahore. A dusty locality, it seems to be suffering from every imaginable civic problem: broken roads, muddy streets, uncollected trash and a drain full of toxic waste passing by. And then there are many other problems that an outsider will start discerning as she talks to local women: poverty, domestic violence and disempowerment just being a few of them.

Another constant problem that women in Hudiara face is that many of them are not registered to vote. The village is a part of a National Assembly’s constituency (NA-132) where women’ votes constitute only 39.9 per cent of the total registered votes.

On a recent day, a Lahore-based non-government organization (NGO), Sangat Development Foundation, has sent a team to Hudiara to register women voters there. The team is accompanied by a mobile unit of the National Database and Registration Authority (Nadra) which verifies women’s identity documents before they are registered as voters.

Most local women do not have a valid computerized national identity card (CNIC) which is a necessary condition to register as a voter. The mobile unit helps them apply for their CNICs on the spot. This is a major relief for them.

Nazeeran Bibi’s case illustrate the problems local women face in the process of getting CNICs. Wearing tattered clothes and nearly out of breath due to the effort she needed to make to reach Nadra’s mobile unit, she has a torn paper in her hand. Issued by Nadra, it is written in English -- a language she cannot read or understand. It, indeed, is a receipt that states that she applied for the renewal of her CNIC – which expired in 2007 – earlier this year at a Nadra office in Lahore which she has visited twice since then, spending both her hard-earned money and time. Yet, she says, she has not received her new CNIC because Nadra officials tell her to bring a ‘token’ she was given at the time she submitted her application. She seems to have lost that token but Nadra would not give her the CNIC without it -- so she has come to the mobile unit to sort out the matter.

Muhammad Azam, who is working as the local contact person for the voter registration team, says the primary reason why female voter count is low in his village is that the new registration system is too complicated for the villagers to understand and follow. An aspiring candidate for a coming local government election, he explains how under the old voter registration system election candidates would go to each house to register everyone, including women, on the spot because more registered voters meant more potential votes. But, as Muhammad Azam says, the new digital system of voter registration requires people to have so many documents – such as birth registration certificates, CNICs, marriage deeds etc -- that men often do not take the trouble of registering the votes of women from their households.

Since these women also generally do not need their identity documents – because they hardly venture out of their homes – they are usually careless about them. As a result, says Muhammad Azam, “the documents women need to register their votes are either lost or in a poor condition.”

Even when the documents are in a good shape, women are told to bring with them their male family members to verify their identity.

These men are either reluctant to let women in their families be in the public space or they are not present when they are required for verifications.

The first type of problem is very obvious in Hudiara.

Sameena, a local women, says she does not intend to vote because, as she says, male elders in Hudiara “frown upon women appearing in public for activities such as voting.”

She has arrived at the mobile unit to get her CNIC made not to get registered as a voter but because she needs it for the admission of her children in schools. She is accompanied by her husband and brother and says: “Casting a vote is a man’s business, not a woman’s.” She also adds: “I don’t think my vote matters.”

Sadia, a 30-year-old woman, is also unlikely to vote even after her vote is registered. She is visiting the mobile unit along with her husband who teaches at a local madrassa to have her CNIC renewed. She says she has no time for such things as politics and voting. “I work day and night for a living. When I am not working, I am tending to domestic chores which take up whatever is left of my time.”

Where have all the women gone?

Women constitute 49 per cent (101.314 million) of Pakistan’s population as per the 2017 Census but many of them, despite being in the voting age, are not registered to vote. According to the data released by the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), the number of female voters registered for the 2013 general elections was lower by 10,994,970 than that of male voters.

The highest gender gap, as can be seen in the table above, was reported from the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata) which have now been merged in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Women voters constituted only 34.3 per cent of the total votes registered in Fata. Balochistan ranked second. Female voters there were only 42.6 per cent of the total registered voters.

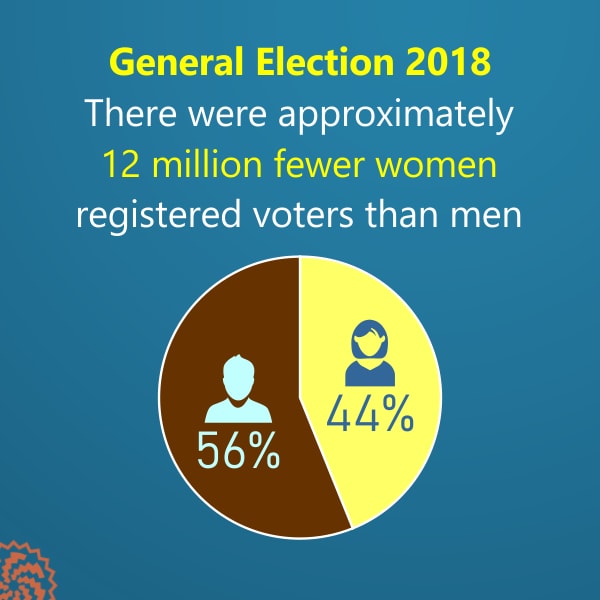

This gender gap only increased before the 2018 general elections -- to 12.49 per cent as compared to 10.97 per cent in 2013. Out of a total of nearly 106 million voters registered across Pakistan for the last election, female voters were 46,731,147 or 44 per cent of the total. This means there were approximately 12 million fewer women on the electoral roll than men.

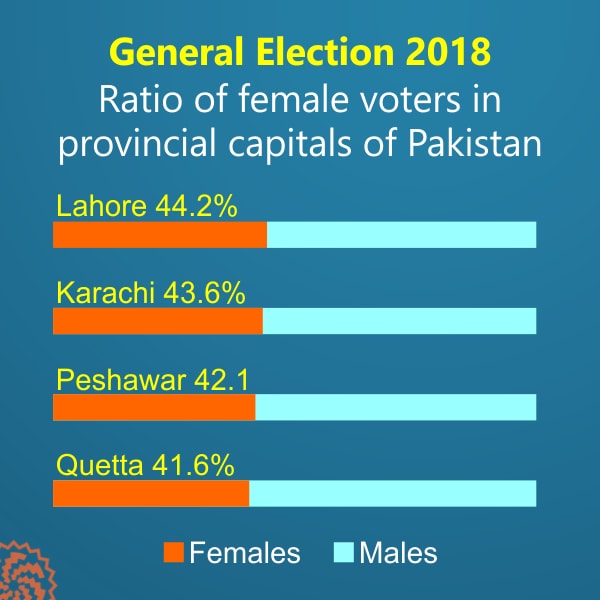

The electoral rolls used in the 2018 election also show that gender gap existed as much in the rural areas as in the urban ones. In Kyber Pakhtunkhwa, for instance, women voters in Buner, a mostly rural district in the mountainous Malakand Division, accounted for 43.8 per cent of total registered voters whereas the share of women voters in Peshawar, the largest urban centre in the province, was only 42.1 per cent.

Same holds for Balochistan where Jaffarabad, a rural district, had a higher share of women voters (45.7 per cent) than the provincial capital Quetta where they constituted 41.6 per cent of the total registered voters. Similarly, the percentage share of female voters in Sindh’s rural district of Jacobabad (at 46.5 per cent) was higher than that it Karachi, the country’s single largest urban space, where it stood at 43.6 per cent.

Punjab, too, demonstrated a similar pattern. In Lahore, the capital of the province, registered women voters constituted 44.2 per cent of the total votes. In comparison, they constituted 48.5 per cent of the total votes in Chakwal which is largely a rural area. In fact, there are areas within Lahore where the share of women voters in total votes is below 40 per cent.

Will the gap ever decrease?

The parliament has empowered the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), through the Election Act 2017, to fill this gap. The act gives the commission the authority to nullify election results in any constituency where women’s turnout remains less than 10 per cent. It exercised this authority in 2018 when it ordered re-election in a provincial assembly constituency, PK-95, in Lower Dir district on the ground that the turnout of women voters there was less than the legally acceptable number.

The election commission has also initiated a project to increase the registration of women as voters – with technical and financial support from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Trust for Democratic Education and Accountability (TDEA), which is a conglomerate of Pakistani non-government organizations, International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), which is an American non-profit organization, and an America-based development company, Development Alternatives Incorporated (DAI).

The commission has also partnered with Nadra and Pakistani NGOs like Sangat Development Foundation to improve female voter registration in 79 districts where their registration and turnout have been significantly low. The main purpose of this campaign is to provide CNICs to women without them having to travel to a far off government office in a big city. Instead, Nadra’s Mobile Registration Centers reach these women in their own villages – just as one such centre did last month in Hudiara.

A field officer working with Sangat Development Foundation, however, says the amount of work still to be done is massive. Out of the 1.2 million female voters missing in Lahore in 2018 election, only 100,000 have been registered so far. Huge amount of financial, technical and human resources will be required to register the remaining 1.1 million before the next election – though by then the total number of missing voters might have increased by another couple of hundred thousand.

Figures released by the election commission, as shown below, testify to the fact that the numbers have barely budged after all the earlier voter registration campaigns. In fact, the percentage in the case of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has remained the same.

Bushra Khaliq, who heads the Women in Struggle for Empowerment Wise (Wise), an NGO based in Lahore, has worked with both the election commission and Nadra in female voter registration campaigns. She complains that both these institutions are still working at a leisurely pace. “While the process of voter registration is computerized, most of the preliminary paper work is still being done manually,” she says.

Another problem that emerges often during the process is that Nadra officers handling torn and ill-preserved documents take extra care and extra time before using them lest they fall into some trouble because of them, she says. This increases the time they spend on accepting each application for a CNIC, she adds.

Nadra, according to Bushra Khaliq, also works haphazardly.

This, indeed, is on display fully during the voter registration campaign at Hudiara. The mobile unit there is surrounded by so many men that many women, feeling uncomfortable by their presence, start going back home.

Huda Ali Gohar, who works as a public relations officer at the election commission’s Lahore office, claims that many steps are being taken to address these problems. In order to improve the provision of CNIC for women, she says, Nadra has stipulated that all its centers will entertain only female applicants on Saturdays. She also says that activists and NGOs have been engaged to create awareness among women regarding their voting rights as well to inform them how to register as voters. “Though these initiatives have been affected negatively in recent months due to COVID-19, a new phase of female voter registration campaign is being launched in November 2020,” she adds.

Huda Ali Gohar also claims that all the gaps and shortcomings in the previous campaigns have been identified and discussed in a recent meeting between Nadra and the election commission. The participants of the meeting decided to increase the number of mobile centers and raise the number of officers and organizations working on female voter registration, she says. “Dedicated windows at every Nadra office are also being set up for women to further facilitate them in getting their CNICs.”

Way forward

Sarwar Bari is the national coordinator at Pattan Development Organization, an NGO that has been working to promote women’s political participation for many years. He believes the best possible solution to bridge the male-female voter gap is the use of digital technology.

“The village-to-village campaigns launched by the election commission in collaboration with Nadra and NGOs are an old-school practice which requires a lot of human and financial resources and still does not guarantee the desired results,” he says and suggests that a fully automated system of voter registration should be set up urgently.

He also suggests that Nadra should automatically issue a temporary CNICs and a temporary voter card to everyone as soon as they turn 18. “These documents should be changed with permanent ones after making all the necessary verifications – and that too digitally,” he says.

This, however, will still leave out hundreds of thousands of older women who have never been registered as voters or who do not have CNICs. Bari does not offer a quick solution for their registration as voters but there must be a technological solution out there for that as well. Without finding and implementing that solution urgently, Pakistan’s gender gap in voting runs the risk of widening further – and forever.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 16 Nov 2020, on its old website.

Published on 3 Jun 2022