Najma Bibi’s fellow teachers never respond to her greetings because she follows Ahmadi religion.

She has been teaching at various state-owned schools in Jaranwala tehsil of Faisalabad district for the last 31 years. Shortly after her husband’s death in 2013, she was transferred to a new school. Unexpectedly for her, she was received very coldly by her fellow teachers there.

Initially, she expected that the behaviour of the school staff would turn better in the course of time but, on the contrary, their behaviour towards her grew worse with each passing day. “Let alone be able to dine with my colleagues, I am not allowed to even enter the staff room,” she says.

The situation in the school she was transferred from, though, was altogether different. She was never discriminated against on the basis of her faith there. It was perhaps because of the fact that an Ahmadi woman, who is also her relative, was her headmistress. But at the same time, she acknowledges, the school staff was also respectful enough towards her to accommodate religious differences.

Najma believes that a group of around five teachers at her current school hates her. They, according to her, have also gradually convinced the other staff to join them. “This is the reason why no school staffer attended the wedding of my son in 2015. Similarly, they don’t let me become a part of their own joys and sorrows.”

Zainab also faces similar social attitudes premised on religious hatred.

A resident of central Punjab’s Chiniot city, she, too, is a follower of Ahmadi faith. Married for four years, she is also the mother of a one-year-old daughter which means she cannot leave home to do a job or run a business. She, therefore, has set up an online garment selling venture.

Zainab spent 26 years of her pre-marriage life in the town of Rabwah, located near Chiniot, which is the religious and administrative headquarters of Jamaat-i-Ahmadiyya in Pakistan. During her life in Rabwah, she says, she was never subjected to any religious discrimination for the obvious reason that 90 per cent of the town’s approximately 55,000 population is Ahmadi.

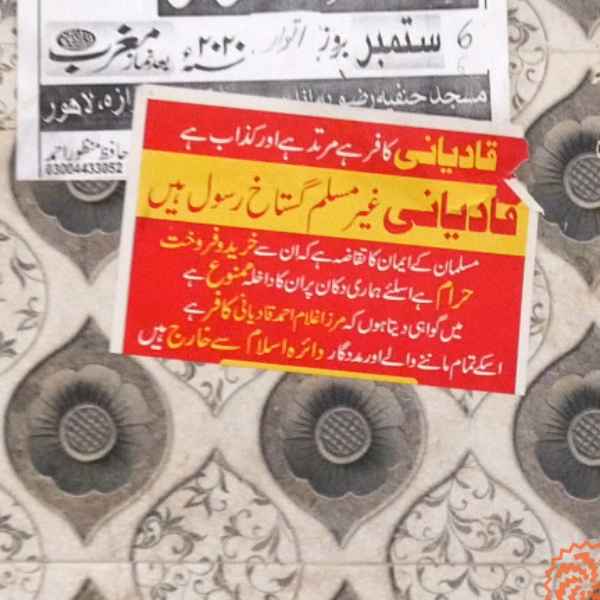

During the short span of her business career, however, she has to endure a number of incidents of religious discrimination as she often comes in contact with people who have a deep hatred for her faith. “After knowing about my religion”, she says, “a number of garment dealers have severed business ties with me because they believe that having business relations with an Ahmadi is not in line with the injunctions of Islam”.

This is similar to what many shopkeepers across Pakistan do: pasting written warnings at their shop-fronts that Ahmadis are not welcome inside.

Nimrah, 21, an Ahmadi student at a private university in Lahore, says the societal hatred against her faith has forced her to have limited social interactions, confining them to her close relatives. She loves recreational activities but, always obsessed with the feeling that her religion is not liked in Pakistan, she has stifled her desire to hang out and eat out with non-Ahmadis.

The first 10 years of her life were spent in Rabwah and then her family shifted to Chiniot where, while at school, she did not realise initially that she was different from other children. Soon, however, her classmates started teasing her because of her faith. Some of them showed their dislike towards her religion overtly while others feigned sympathy and wanted her to convert to Islam. They would say to her: “you are such a nice person but we feel sorry for you that you are not a Muslim”.

Such attitudes continued chasing her even after she moved to Lahore and got admission in a university believed to be an enlightened and diverse place. She says her fellow students not only publicly express provocative views about Ahmadi faith but also declare that its followers are liable to be killed.

Some of them also accuse her of hiding her faith but she says she never conceals her religious identity. “Whenever someone asks me about my religion, I say I am an Ahmadi.”

The unique style of her burqa in any case gives away her religious identity even when she may not like to. Most, if not all, Ahmadi women wear this specific burqa when they are in the public.

Nimrah’s sister is among those few who do not sport an Ahmadi burqa. She avoids using it because she is studying at a university in Lahore where religious extremism is rampant among students. So, in order to stay safe, she prefers to hide her religious identity.

Dr Nida Yasmeen Kirmani, an associate professor of sociology at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), analyses the discrimination faced by these Ahmadi women and says that religious hatred towards their community has registered a sharp increase during the last three decades. The main reason behind this increase is “the growing role of Sunni Muslim groups in power politics and an unabated hate speech against Ahmadis sponsored and promoted by different religious organizations often under the state patronage.”

As a matter of fact, the state is directly involved in promoting extremist religious and social attitudes towards Ahmadis. This is evident from the fact that they were declared non-Muslims by the Parliament in 1974. Additionally, in 1984, Ziaul Haq’s military dictatorship made it a punishable offense for an Ahmadi to so much as converse like a Muslim.

Between the devil and deep blue sea

Like many young Ahmadi girls, Alina moved to Lahore from Rabwah for higher education 12 years ago but her family married her off when she was still doing her bachelors. She could resume her education only after her marriage. Now 28, she has one child.

Ahmadi women, according to her, are in a double jeopardy. On the one hand, she says, Ahmadis being a small religious group in Pakistan (with a total population of 485,000 people) are always exposed to the excesses of Muslim majority. On the other hand, according to her, Ahmadi families and Jamaat-i-Ahmadiyya do not let Ahmadi women live an independent life.

From the everyday issue of selecting a dress to such important questions as education and marriage, they have no say in any of them, says Alina. The men in their families decide all these things in accordance with the instructions of Jamaat-i-Ahmadiyya.

Alina says she cannot even wear a burqa of her choice because, according to her, Jamaat-i-Ahmadiyya has prescribed a burqa design which is religiously followed by all the tailors in Rabwah.

Officials of Jamaat-i-Ahmadiyya Pakistan clarify that although they want all women belonging to their faith to live their lives in accordance with religious injunctions, they are never forced to do anything that they do not like. Alina, on the contrary, says she was severely criticized by her relatives for giving up burqa. Even her own family members scolded her that it was unbecoming of a true follower to disobey the religious obligations.

She, simultaneously, believes that such injunctions are generally applied more strictly upon women from middle class and poor families. “If you come from a finically and socially strong family, it is not a big deal for you to ignore these orders.”

She backs up her claims by referring to a foreign-based Ahmadi woman who often visits Rabwah to sensitise women on the importance of education and other social issues. “That woman neither wears a burqa nor covers her head.”

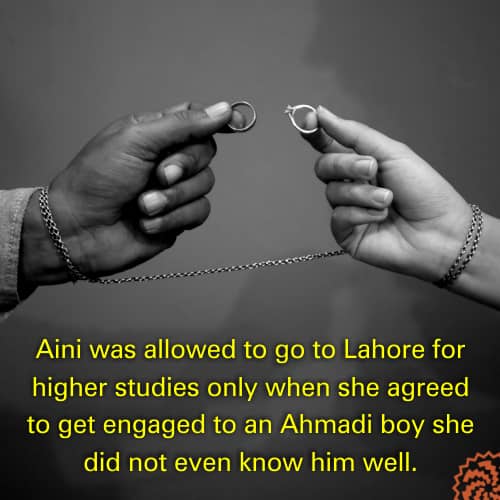

Aini, a resident of Rabwah, has similar complaints.

A few years ago, when she sought her parents’ permission to go to Lahore for studies and stay in a hostel, they made their permission conditional to her getting engaged with an Ahmadi boy first. Aini, then 20, did not know much about that boy but she consented to accept him as her fiancé just to continue her studies.

While living in Lahore, though, she reached the conclusion that her ideas and attitudes were entirely different from those of her fiancé. So, she started pressuring her parents to end her engagement with him and, as a signal of that, returned the engagement ring to him.

Even if she succeeds in breaking up the relationship, Aini says, she will eventually have to marry none other than an Ahmadi boy. No matter whether she likes him or not.

An Ahmadi woman, in fact, can never marry a non-Ahmadi man of her own choice. If she does that, Aini says, she would face a social boycott from both her family and Jamaat-i-Ahmadiyya.

Dr Kirmani, however, does not regard it as an issue specific to Ahmadi faith. This not limited to Ahmadis, she says. Every religion, sect and social group, indeed, has tied its collective honour and group identity to its women, she argues. “This link gets challenged whenever a woman belonging to that group demands self-empowerment.”

Also, she says, whenever a minority religious group feels that its identity and survival are in jeopardy, its men intensify efforts to control their women so that they do not get married to men professing other religions. This way, she says, they try to ensure the biological continuity of their religion. This, according to her, explains why, “women belonging to all minority groups in Pakistan, including Ahmadis, face a dual oppression.”

Note: The names of Ahmadi women interviewed for this report have been changed so that their private and public lives are not affected.

Published on 20 Oct 2021