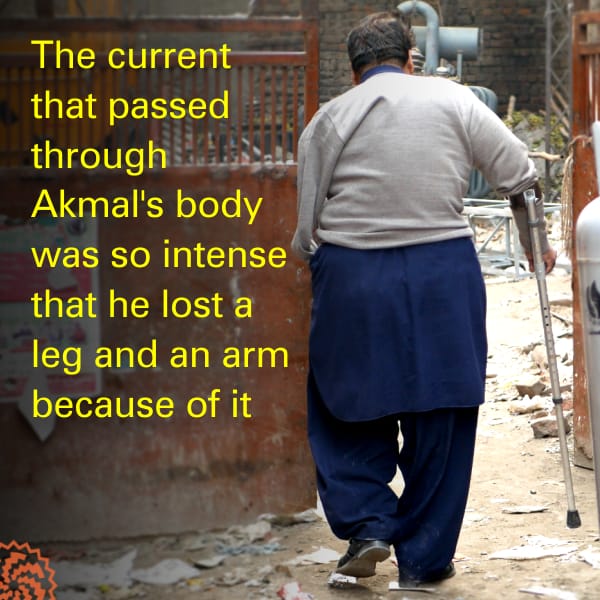

An accident three years ago changed Rana Muhammad Akmal’s life forever.

On the morning of 10th November 2017, he was doing his duty as an electricity lineman at Lahore’s Shah Alam market when his boss, a line superintendent, sent him to restore electricity at Fawwara Chowk locality in the same area. A little while later, Akmal was repairing an electricity transformer on a pole when a powerful electric current ran through his body and he got stuck to the pole.

“The shock made me unconscious. I do not remember what happened to me after that,” Akmal says. He remained hanging with the pole for half an hour. Finally, some passersby took him off the pole and shifted him to the Mayo Hospital on a motorcycle rickshaw.

According to workplace regulations, electric flow through the pole should have been cut off at that time. His line superintendent, indeed, had obtained a permit to work -- a copy of which Akmal still has – to ensure that. The presence of the permit implies that electricity should have been restored only after the lineman had finished his work and climbed down the pole.

The line superintendent, however, ordered the restoration of electricity before the completion of work that day, Akmal alleges.

He remained under medical treatment at Lahore’s Wapda Hospital and later at Ghurki Hospital for two years. The current that passed through his body was so intense that he has lost a leg and an arm to it.

Akmal now works as a telephone operator at Shah Alam market subdivision of the Lahore Electric Supply Company (Lesco) where his work hours start in the morning and end in the afternoon.

Whose fault is it anyway?

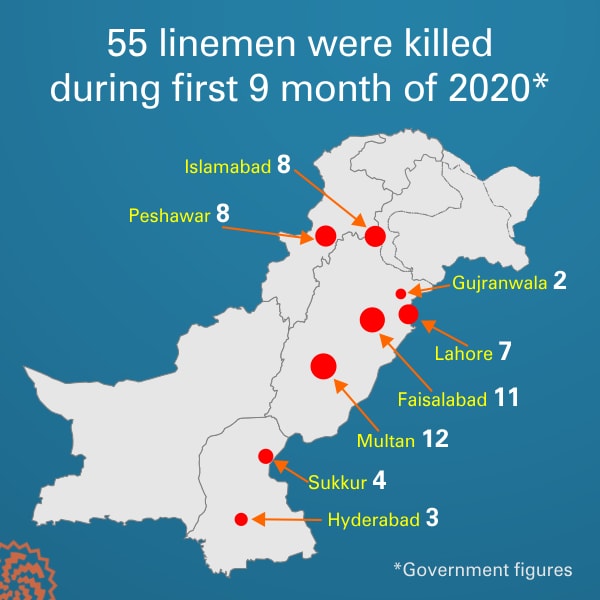

Scores of linemen meet accidents each year across Pakistan. According to the government data, at least 55 linemen died of electrocution only in the first nine months of 2020. Seven of these accidents occurred in Lahore, three in Hyderabad, four in Sukkur, two in Gujranwala, 11 in Faisalabad, 12 in Multan, eight in Peshawar and eight in Islamabad.

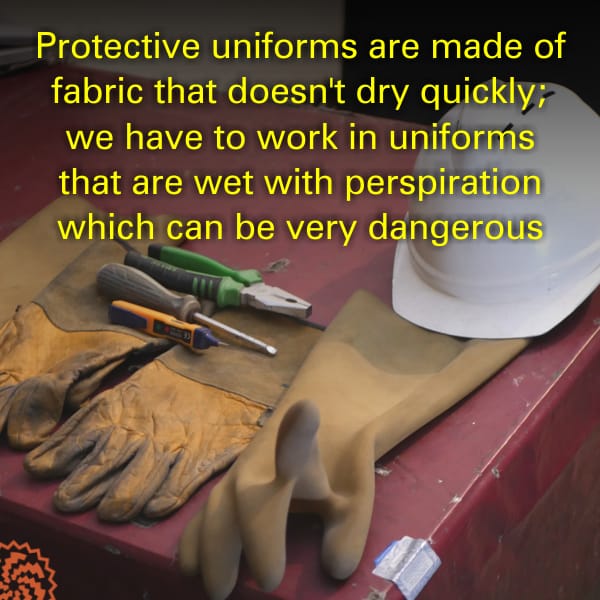

Officers and linemen working with Lesco say the basic reason behind all these incidents is that precautionary measures are not fully followed while electricity lines are repaired. A sub divisional officer (SDO) says Lesco and other electricity distribution companies either do not spend any money on the provision of protective gear -- uniforms, gloves, helmets and shoes etc -- or linemen do not get access to these things.

The linemen say whatever gear they get is so faulty that using it poses another set of problems. A lineman working in a Lahore suburb says “the protective uniforms are made from a cloth which takes very long to dry so, in summers, we have to work in uniforms wet with perspiration which can be very dangerous because wet clothes can be strong conductors of electricity.”

The linemen also say they “often go to work without wearing these uniforms because these do not fit well in most cases”.

Ageing wires are another cause for accidents. The metal parts of these wires become exposed at many places due to friction, says a lineman in Lahore. “There are also often so many wires passing through a single pole that it is almost impossible to determine which one is going where,” he says.

Safety gear required for a lineman

And then there is the issue of ‘double sourcing’ which means that an area, or a shop or a house gets electricity simultaneously from two different subdivisions. A lineman working on such sites manages to get the power closed down from his own subdivision but the current flowing from the other subdivision still remains in the wires which can cause in an electric shock to him.

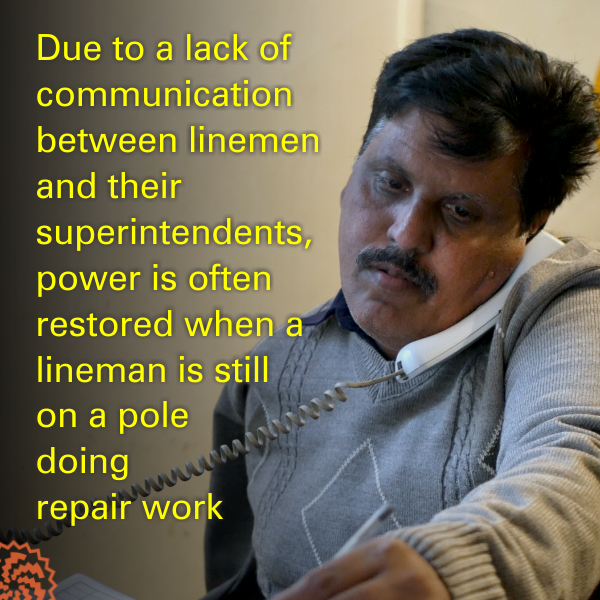

All these problems become more frequent in summers when repairs are often needed at more than one place at the same time. In such situations, linemen often lose contact with their line superintendents, resulting in electricity restoration even when they are still working on a pole.

An SDO stationed at the Lesco headquarters says precautionary measures are often also violated because some influential person residing in an area where a fault has occurred wants to get the problem fixed as early as possible, treating it as a matter of his personal prestige. “These people put so much pressure on us that the linemen cannot concentrate on their work which results in accidents,” he says.

Problems galore

Officially, the linemen work in three daily shifts -- morning, afternoon and night – with each of them having to spend a minimum of eight hours at work. In practice, this is rarely followed and a lineman often ends up working more than eight hours.

The main reason for this is staff shortage at Lesco and other electricity supply companies. In general, a lone lineman is working in each shift at each subdivision though, as per rules and regulations, there have to be at least two linemen and two assistant linemen there.

A lineman at Lahore’s Shahdara subdivision says since line superintendents have to stay at work 24 hours a day so they call the linemen to work anytime they are needed. “In summers, we often end up working 24 hours a day. If we refuse to work in such situations then we are threatened that we might be terminated from our jobs,” he says.

Besides this extraordinary work schedule, the lack of facilities also makes a lineman’s work difficult. For example, the linemen have no vehicles at their disposal to carry their equipment to maintenance sites. “We have to deliver our tools, safety gear and long ladders to these sites on our own. If we do not have our motorcycles available then we have to deliver these things on carts,” says the lineman working in Shahdara.

According to him, most branches of electricity supply companies “also do not have buckets (a crane-like platform which carries a lineman while he is working on a faulty line) so we have to hang on to poles while working”. In this situation, he says, “even a minor mistake can be fatal”.

It is for these reasons that a Lesco line superintendent compares a lineman’s work to that of a surgeon’s. “The only difference between the two is that a mistake made by a surgeon results in the death of a patient while a mistake made by a lineman takes his own life,” he says.

The negative attitude of seniors towards juniors and a highly insulting behaviour of the public towards the linemen are also important contributing factors to their miserable working conditions.

According to Jabbar Ahmad, a lineman working in Shahdara, “our officers treat us like we are animals”. The general public also treats us in a humiliating manner, he says. “People hurl insults at us whenever they suffer a power breakdown.”

Compensation conundrum

Ahmad’s father was also a lineman who died in 1992 in a work-related accident. His family was paid 150,000 rupees in compensation and two of his sons – including Ahmad -- were hired as linemen.

A few years ago, Ahmad’s brother was working on an electricity pole when he informed his SDO that his assignment could become fatal if electricity was not turned off immediately. “The SDO instead abused my brother and ordered him to stay on the pole come what may,” says Ahmad. A little while later, an electric explosion occurred and “my brother fell to the ground, becoming disabled for life”.

Recalling that incident, he says the real struggle of the victims of accidents starts after they have been injured or dead. “Our department does whatever it can to save the skin of senior official while throwing the linemen under the bus,” he says and adds that “officers treat each other as if they are siblings”.

Akmal’s case explains how that happens.

“My line superintendent told Lesco that I had gone to the site of the accident for personal reasons but an inquiry committee that looked into the incident decided in my favour because I had the ‘permit to work’,” he says. A second committee, however, put the blame of the accident on him and it was only after a third inquiry found him in the right that Lesco agreed to pay compensation to him.

If he had been found to have been in the wrong, he would have gotten nothing.

The linemen who get injured or die as a result of accidents are given compensation as per a set policy. For example, the Pakistan Electric Power Company (PEPCO) has recently decided that it will give the following compensation to the dead/injured linemen or their families:

- 3,500,000 rupees

- Permission to stay in a government house till retirement

- A job for a child or a widow according to his/her education

- Medical bills

- Free education for his children until graduation

- Free home electricity supply

Most branches of electricity supply companies do not have buckets so the linemen have to hang on to poles while working.

Many linemen, however, claim that all these benefits are given only to the families of those who die while on duty. People with partial or full disabilities often complain that they do not receive these benefits – at least not all of them.

Akmal, for example, says Lesco has paid him 3,150,000 rupees as compensation “but, rather than giving me more financial benefits, it has taken back some that I was receiving earlier”.

Lesco has deprived him of danger allowance which was about seven thousand rupees a month because he is working as a telephone operator now. “Consequently, my monthly salary has decreased after the accident.”

He similarly alleges that he has not been given a job even though he qualifies for one under the compensation package. “Lesco is also not willing to pay for the treatment of my damaged arm,” he claims further.

Other linemen complain that the general liability allowance (GLI), deducted from their monthly salaries, is given to the families of only those who die at work. Those who get injured or disabled do not get anything from this insurance scheme. “Lesco’s position is unequivocal: if someone needs the insurance money then he will have to sacrifice his life,” says a lineman in Lahore.

According to some official documents, Lesco established a separate entity in 2019 for the payment of compensation. This entity has paid 3,500,000 rupees to each lineman who suffered a fatal accident in 2020 and the payment of remaining benefits is at various stages of being processed.

No official figures, however, are available about the compensation given to the victims and their survivors in earlier year. The linemen say they have to knock at every other door to get what they should have been given.

This explains why most of them remain wary of talking to the media. They fear that making their plight public might enrage their officers who then might stop the payment of the benefits to them.

This report was first published by Lok Sujag on 14 Jan 2021, on its old website.

Published on 31 May 2022